For humans, being able to orientate ourselves is crucial. Getting lost on the level is bad enough, but not knowing which way is up is worse. Most of the time gravity ensures that’s not a problem – but what happens in space without that assistance?

The International and Tiangong Space Stations lie very much within the Earth’s gravitational well, being about 400 kilometers (240 miles) up. At such a small distance compared to Earth’s radius, gravity is almost 90 percent as strong as at sea level. However, astronauts on the stations, and the satellites themselves, don’t experience this because they are in free-fall.

They don’t plummet towards the surface because they are also moving very fast. If the Earth’s gravity were to magically turn off somehow, they would fly off into space on a tangent to the orbit, like a ball on a string whirled around a child’s head when let go.

Trainee astronauts experience weightlessness during periods of free-fall on the “vomit comet”; once in space, the weightlessness is sustained. Since the whole station is falling together, there is no sensation of falling, so people and objects float.

However, there is a reason the plane officially known as KC-135 0-G has its unappetizing nickname: humans have spent millions of years evolving in a gravitational field, and losing it can prove unpleasant. For many, losing it leads to disorientation and nausea.

Conditions in orbit used to be referred to as “zero-gravity” or “zero-g”. That’s been dropped in favor of the more accurate term “microgravity“. After all, even if the gravitational effect of the Earth is cancelled out, everything with mass has a gravitational pull, so astronauts experience a tiny amount of gravity from the space station and even from each other.

These forces are so weak, however, our bodies don’t really register them. Moreover, the space station is all around them and pulling in every direction, even more strongly towards where the mass is greatest. Consequently, in orbit, we can’t get a sense of up and down from gravity.

We Can Make Our Own Up

However, that doesn’t mean all directions have to be the same. Our body uses both our inner ear’s capacity to feel gravity and acceleration, and our eyes’ registration of our location relative to other things for orientation. We get motion sickness or space adaptation syndrome when these two contradict each other, but the fact our eyes also provide orientation means it is possible to make our own up and down. We might not sense it, but we can see it.

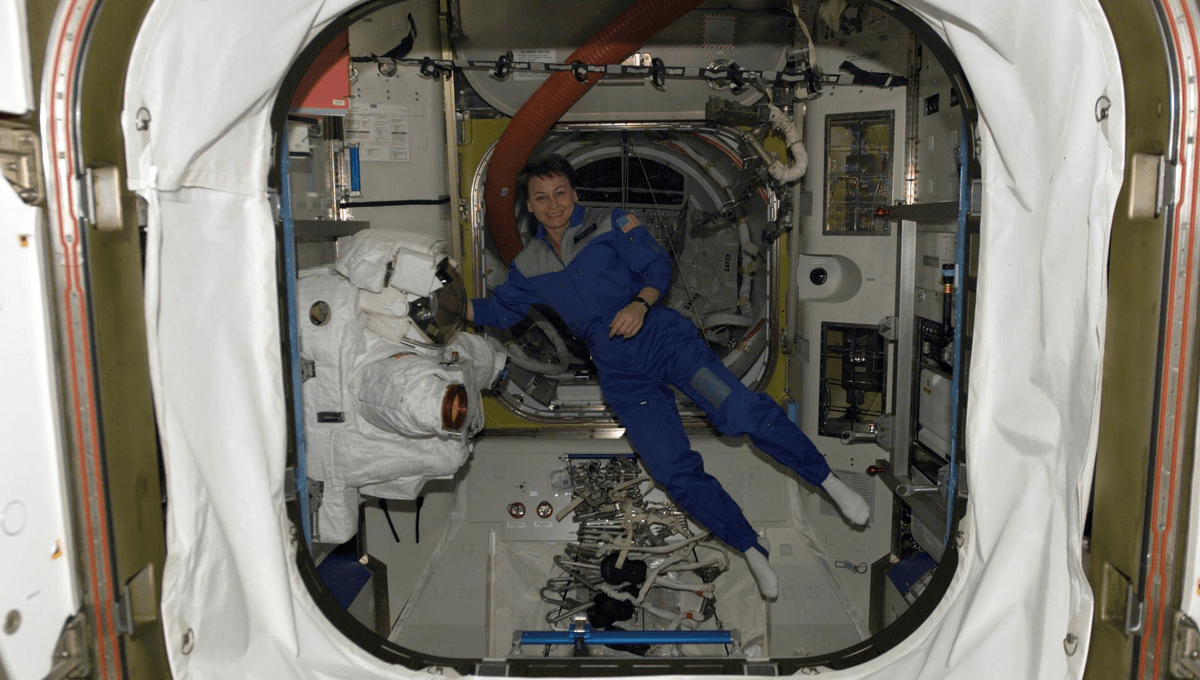

One way to do this is to have everything within the space station orientated the same way. For example, the ISS is designed so most of the lights come from one direction, which then becomes a ceiling, while the opposite is the floor. It would be possible to have notices on the walls randomly orientated, but to do so would be confusing, so instead they are generally placed the same way. That gives astronauts an incentive to usually stay orientated with their head towards the “ceiling”.

The second way a sense of up and down can be created is external. Using the Sun or stars for orientation would be quite problematic, but the Earth is much more convenient.

Like the Moon, the ISS always keeps the same face to the Earth. Also like the Moon, this doesn’t mean it doesn’t turn. Instead, it rotates with the same period as it orbits. Being much closer to Earth than our natural satellite, the orbit is much shorter – 90 minutes instead of a month – so the turning is faster, but not enough to be a problem. There are several advantages of this. Besides offering consistency to the astronauts, radio transmitters don’t need to move much relative to the rest of the station. Moreover, the same gravitational forces that cause moons to keep a constant face to their planet apply to artificial satellites as well. It’s easier not to fight them.

Since 2010, the station has had the cupola, a module whose seven windows offer panoramic views of the home planet. Before that, astronauts had to rely on small portholes. The continued presence of these portholes, however, means that in many parts of the station, astronauts are reminded as to the Earth’s direction, which becomes a default “down” or nadir.

All “explainer” articles are confirmed by fact checkers to be correct at time of publishing. Text, images, and links may be edited, removed, or added to at a later date to keep information current.

Source Link: Is There An Up And Down In Space?