Madagascar is home to some of the world’s most curious wildlife, but deforestation and the exotic pet trade are pushing some species to the brink of extinction. Now, new research has established that it would take evolution 3 million years to return the species that we’ve already lost in the region, but more than 20 million if currently threatened species were to follow suit.

Reaching the conclusion involved building a first-of-its kind dataset that looked at the evolutionary relationships between species endemic to Madagascar. A team of biologists and palaeontologists tracked the island’s history back 2,500 years to when humans first became a permanent feature, and looked at a wide range of already extinct animals known only from the fossil record.

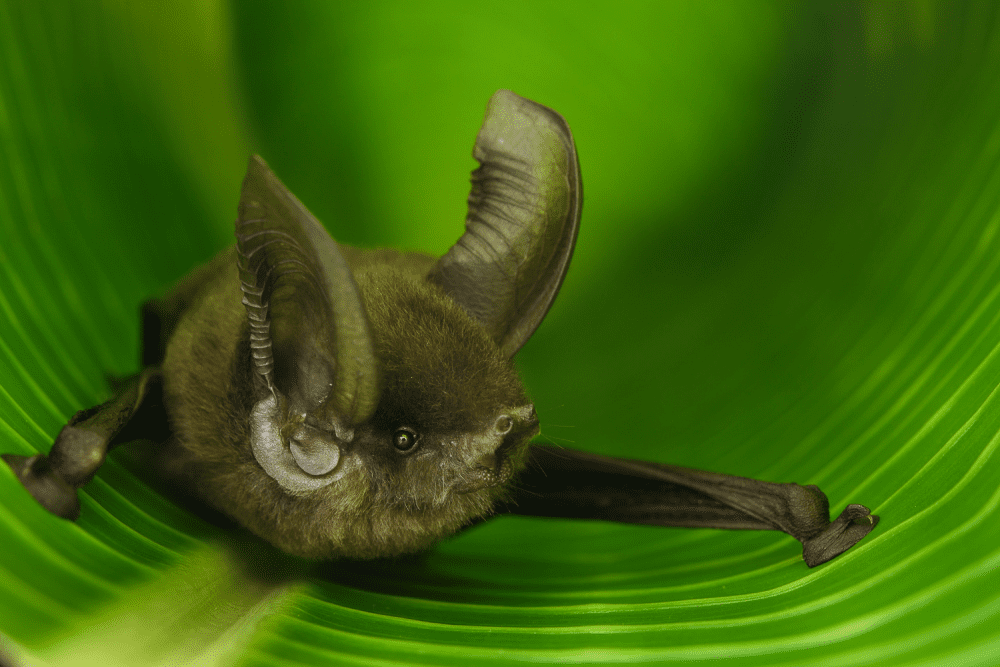

In that stretch of time, the island showcased some remarkable creations, including the world’s smallest chameleon and a sucker-footed bat still found on the island today, as well as a lemur that lived between 500 and 2,000 years ago that was about the same size as a gorilla.

In total, the team created a listed of 249 species, 30 of which have already been lost to extinction and a further 120 of which are currently classed by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as threatened with extinction. Tracking those animals’ histories revealed that it would take evolution around 3 million years to recover the diversity of species that have already gone extinct due to human interference, but that that number could go as high as 23 million were we to go on to lose those species currently classified as endangered.

The Madagascar sucker-footed bat (Myzopoda aurita) belongs to an ancient family of bats that is found only on Madagascar. Image credit: Chien C. Lee

“It’s abundantly clear that there are whole lineages of unique mammals that only occur on Madagascar that have either gone extinct or are on the verge of extinction, and if immediate action isn’t taken, Madagascar is going to lose 23 million years of evolutionary history of mammals, which means whole lineages unique to the face of the Earth will never exist again,” study author Steve Goodman, MacArthur Field Biologist at Chicago’s Field Museum and Scientific Officer at Association Vahatra in Antananarivo, Madagascar, said in a statement.

Madagascar is something of a theme park for habitat types, and its diverse landscape has supported the evolution of an incredible cast of animal characters, from spiky tenrecs, to sifakas capable of surviving in the extremes of arid landscapes. However, animals highly adapted to certain patches are also more vulnerable to extinction, and with deforestation being the biggest single threat to the island, many animals are losing their place in the world and facing extinction.

The critically endangered Verreaux’s sifaka is one of the 109 species of lemurs that currently are extant on Madagascar. A total of 17 species of lemurs have already gone extinct. Image credit: Chien C. Lee

The fact is that once a species is truly extinct, it won’t re-evolve given enough time, but the research is intended to demonstrate how much work the natural world put into creating these magnificent animals, and what a loss to the planet it would be were they to slip out of existence under our watch.

“It was already known that Madagascar was a hotspot of biodiversity, but this new research puts into context just how valuable this diversity is,” said corresponding author Luis Valente, a biologist at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center and the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, in a statement. “These findings underline the potential gains of the conservation of nature on Madagascar from a novel evolutionary perspective.”

The study was published in Nature Communications.

Source Link: It Would Take 23 Million Years To Replace Madagascar’s Species If They Disappeared