We’re pretty used, here in the West, to the “national housing crisis”, meaning too few houses being available. In Japan, however, they have the opposite problem: millions of akiya – empty and abandoned houses, strewn across the country, with virtually no hope of occupation.

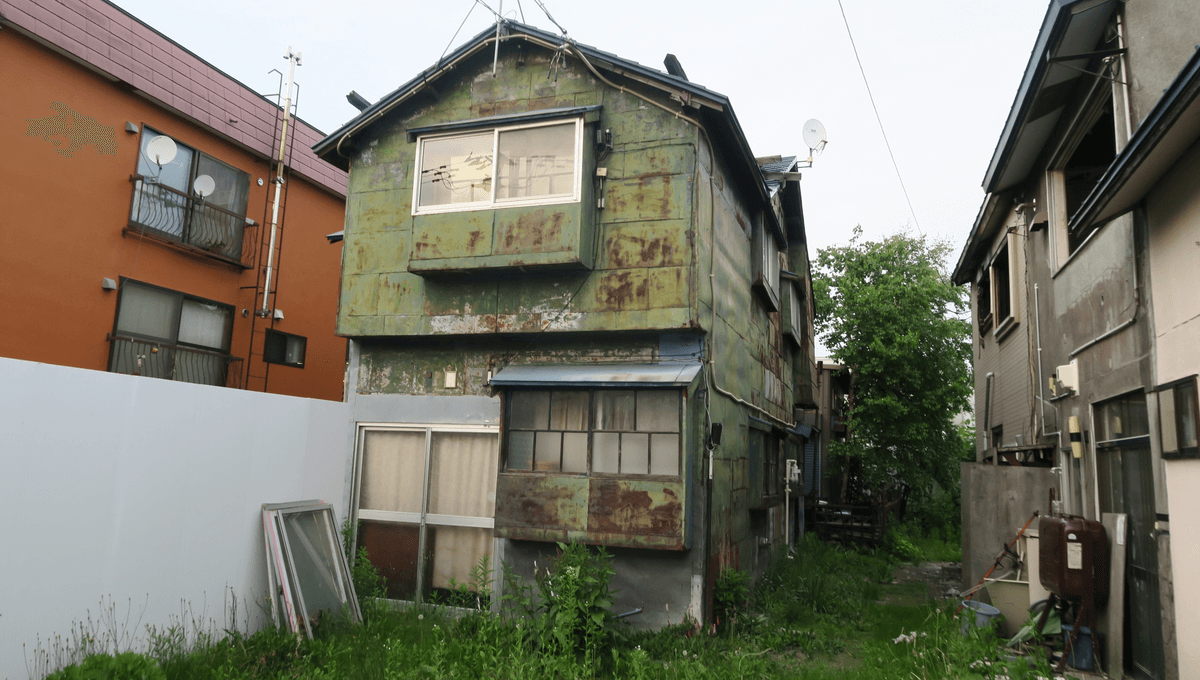

Sometimes called “witch houses”, these buildings are often ramshackle and awkward. Many are extremely rural – less than one in ten Japanese people live outside of a city, leaving the houses of those who left their farmlands and countryside standing empty.

“So many empty houses […] [are] a further deterrent, because people don’t want to live in a terminal village surrounded by ‘ghost houses,’” Chris McMorran, an associate professor in the department of Japanese studies at the National University of Singapore, told Insider back in 2021. Plus, he explained, “there’s still a resistance to repopulate the countryside because […] the lack of accessibility to basic amenities like hospitals and convenience stores puts people off.”

Today – or at least, five years ago, when the last government survey was carried out – there are roughly 8.5 million of these akiya in the country. Depending on which region you’re in, the phenomenon is even more stark: in rural Wakayama, for example, as many as one in five houses are abandoned.

It’s not a new problem: the phenomenon first arose in the post-war period of the 1950s, when Japanese urbanization and industrialization skyrocketed. “Prewar houses were made to last, with the expectation that they would be the home to a family for several generations,” explains Richard Lloyd Parry, The Times’ Asia editor, in a recent report on the phenomenon. “[But] after aerial bombing laid waste to the cities, the priority was to provide housing in quantity, and quality was neglected.”

As a result, new homes in Japan started to be seen as far more temporary than before – expected to last only a handful of decades at most. Homes do not keep their value, let alone increase with age: the overwhelming majority of Japanese people now prefer to buy a newly-built house rather than a pre-owned one, and once a home reaches more than 10 or 15 years old, it could literally be worth less than nothing.

“In Japan, a new home is like a new car, which loses much of its value as soon as it is driven out of the showroom,” writes Parry. “There are streets in which almost every house has been abandoned; there are three in the little cul-de-sac in which I live in western Tokyo.”

Some houses are abandoned when their occupants age out of them. Japan has, by some measures, the oldest population of any country in the world, with close to one in three citizens being over the age of 65. As these people reach old age, many leave their family homes in favor of smaller, more accessible housing; when a homeowner dies, the stigma of their demise can make a home literally unsellable.

And massively compounding this problem is Japan’s infamously low birth rate – a trend which began in the 1970s and has steadily continued to this day. Indeed, in 2022 fewer than 800,000 babies were born in the country of more than 125 million, and the population has shrunk every year since 2009.

All in all, the number of these abandoned buildings is only set to increase. Thanks to a sticky combination of Japan’s property rights laws, lost or untraceable house owners, and economic and cultural barriers, even bulldozing the akiya can be incredibly difficult, and Japanese economic thinktank Nomura Research Institute estimates that a third of the nation’s houses will be uninhabited by 2038.

In short, McMorran concludes, the outlook is bleak.

“This will only get worse,” he told Insider. “The core of the problem is there aren’t enough people to go around in Japan.”

Source Link: Japan's Spooky "Witch Houses": What's Behind This Rapidly Growing Phenomenon?