In Roman mythology, Jupiter was the god of lightning, as well as the sky and dubious sexual encounters in non-human form. It’s therefore highly appropriate that the planet named after him has been revealed to have a lot of lightning too.

Decades after the existence of lightning on Jupiter was revealed by Voyager 1, we still don’t know a lot about it. However, a study in Nature Communications has used the improved time resolution provided by the Juno mission to explore the processes behind Jupiter’s electric discharges and compare them to those on Earth.

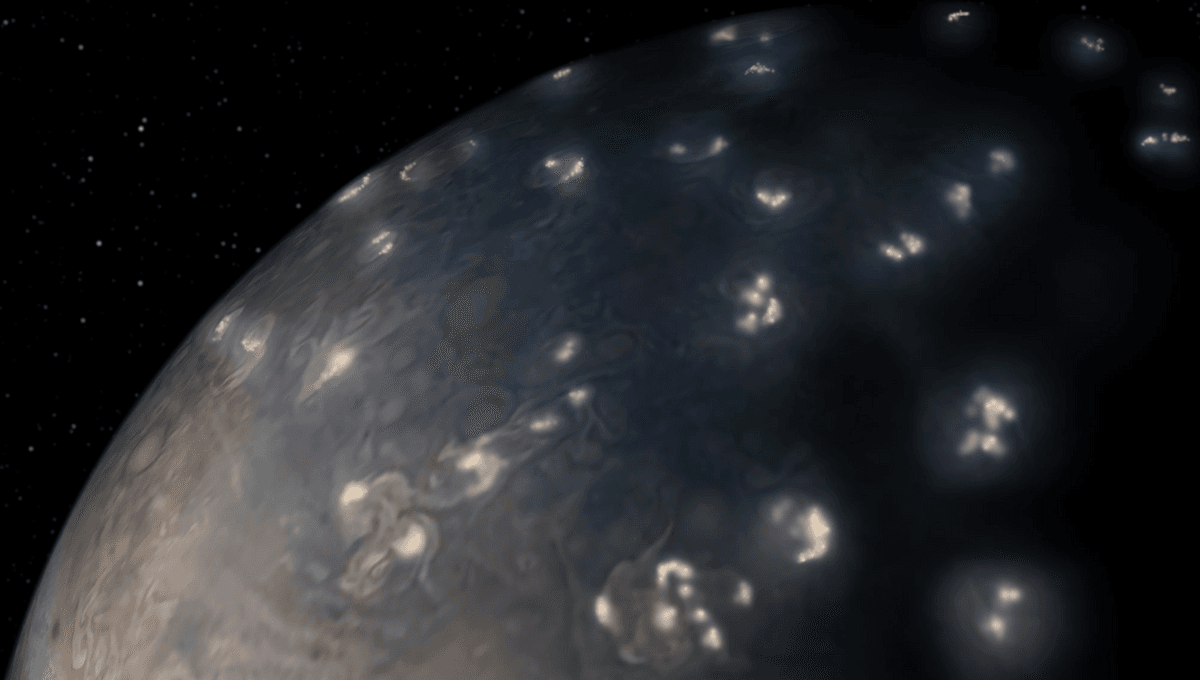

Although Jupiter’s atmosphere is mostly hydrogen and helium, rather than the nitrogen, oxygen, and water vapor that dominate Earth’s, it’s thought clouds of water and ice still form at temperatures a little below freezing. Convective motion driven by heat from deeper inside Jupiter causes charge separation within the clouds, creating powerful electric fields. Just as on Earth, lightning can jump between these as the fields break down, although on Jupiter this mostly happens near the poles, rather than in the topics as we are used to.

As the Galileo mission made its final dive into Jupiter, it detected radio frequency signals, but subsequent analysis showed these were coming from a long way away. Galileo had entered a dry and stable part of Jupiter’s atmosphere, with no thunderstorms nearby. This location may have allowed Galileo to keep sending signals from deeper in Jupiter’s atmosphere than if it had been struck by a lightning bolt, but it also hindered how much we could learn about these events.

By swooping to only a few thousand kilometers above Jupiter’s cloud tops, Juno can detect radio signals from the planet’s lightning, and do so again and again, rather than relying on hitting the right spot in a final blaze of glory.

Juno can measure the radio pulses produced by electricity in Jupiter’s atmosphere with a resolution of an eighth of a millisecond. The paper reports such pulses are typically a millisecond apart. The observations, the authors conclude, “Suggest step-like extensions of lightning channels and indicate that Jovian lightning initiation processes are similar to the initiation of intracloud lightning at Earth.”

The timescales of Jovinian lightning, and the gaps between, are also similar to those in Earth’s atmosphere, with radio signals about a millisecond apart from stepping processes where leaders jerkily jump across the sky.

Some apparent similarities are illusory, the authors suggest. On Earth, there are usually three to six strokes in close-to-ground flashes of lightning, while Jupiter’s radio pulses mainly came in batches of five, but that does not mean the process is the same. “The Jovian pulse groups were very unlikely generated by multi-stroke lightning flashes. In such case, the Jovian strokes would appear in about 30 times faster succession than on the Earth,” the authors write. They consider this “improbable”.

We might expect everything on Jupiter to operate at a different scale, including enormous bolts worthy of a god. On the one hand, the authors conclude that lightning travels at similar speeds within Jupiter’s and Earth’s clouds. On the other, they propose the lightning channels are a few hundred to a few thousand meters long. Although, lightning megaflashes hundreds of kilometers long have been recorded on Earth, most are somewhat smaller than those on the sky god’s planet.

The study is published in Nature Communications.

Source Link: Jupiter’s Lightning Bolts Are A Lot Like Earth's (Only Longer)