Every year, billions of capelins migrate to the Norwegian coast to spawn, and predators take advantage and feast. Scientists analyzing one migration witnessed the largest single act of predation humans have ever seen, as millions of cod attacked a giant capelin shoal over the course of four hours. In the process, they have gained insight into the population dynamics of two of the region’s most important fish.

Capelin (Mallotus villosus) are a small fish that live on plankton and krill in the cold but very productive waters of the North Atlantic. They form an essential layer of the ocean food chain in much the same way anchovies do in somewhat warmer seas. Capelin numbers have crashed in the past, but the immense number of eggs they produce gives them the potential to rebound much faster than many other species.

Capelins are particularly vulnerable to predators when seeking locations to spawn. Their North American counterparts have found another option, but European capelin do this in gravel 2-100 meters (6-300 feet) below the surface.

The biggest beneficiaries are cod, who time their late winter/early spring migration to their own spawning grounds so they can feed on capelin en route.

In 2014, Nicholas Makris of MIT and colleagues used sonar called Ocean Acoustic Waveguide Remote Sensing (OAWRS) to watch the fishes’ movements over a wide area.

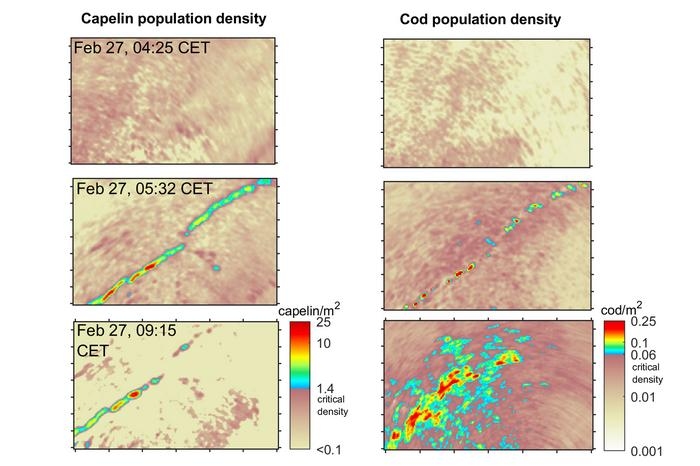

The OAWRS images showing the way both capelin and cod came together and then dispersed in unison.

Image Credit: Courtesy of Nicholas Makris, et al

Early on February 27, 2014, the OAWRS revealed capelin were swimming as loosely clustered individuals – but as dawn was breaking they headed towards the seafloor and coalesced into a shoal tens of kilometers long. Makris and colleagues estimate this contained 23 million fish, weighing 414 tons and acting in coordination.

“What we’re finding is capelin have this critical density, which came out of a physical theory, which we have now observed in the wild,” Makris said in a statement. “If they are close enough to each other, they can take on the average speed and direction of other fish that they can sense around them, and can then form a massive and coherent shoal.” Familiar as shoaling behavior is in many fish, it had never been seen before in capelin.

Small fish shoal partly to save energy, but also because their movements can confuse predators. However, their concentration also makes them a target, including for cod. As soon as the shoal formed, cod made their own shoal – which Makris and colleagues calculate contained 2.5 million fish – and went hunting. An estimated 10.5 million capelin perished before the shoal dissolved a few hours later.

Density waves travelled through both capelin and cod populations, starting at the same locations, faster than individual members of either species can swim.

Predators also shoal, the team write, because; “A predatory shoal is able to break a prey shoal, releasing individuals that become easy targets for predation.”

Although feeding frenzies of other small fish have been featured in documentaries like Blue Planet, revealing nature’s peak abundance, it’s only through technology like OAWRS that we can grasp the size of the event.

“This is happening over a monstrous scale, and we’re watching a wave of capelin zoom in, like a wave around a sports stadium, and they kind of gather together to form a defense,” Makris said. “It’s also happening with the predators, coming together to coherently attack.”

The team doubt events like this pose a threat to regional capelin numbers, noting that off Norway alone the annual migration is estimated to include a thousand times as many of the fish. However, they are worried that rising global temperatures will make some of the capelin’s spawning grounds unsuitable, forcing the population into a smaller number of hotspots.

While tracking the capelin the researchers photographed the snow-capped cliffs of Norway nearby.

Image Credit: Courtesy of Nicholas Makris, et al

In that case, Makris said; “The kind of natural ‘catastrophic’ predation event we witnessed of a keystone species could lead to dramatic consequences for that species as well as the many species dependent on them.” The capelin’s primary feeding grounds are at the edge of the Arctic sea ice each winter. As the sea ice retreats, the journey to their spawning grounds is longer and fewer are likely to make it, at least in a condition to evade predators and be able to spawn.

This isn’t just guesswork: a combination of climate change and fisheries management failures have led to the collapse of capelin populations in the Barents Sea in the past. Sea birds and marine mammals feed both directly on the capelin, and on species like cod that depend on them. If capelin numbers collapse, they will go too.

You might wonder why capelin shoal if it attracts predators, but the observations reveal the capelin in the highest density regions of the shoal were most likely to survive. It’s the ones on the outside who got eaten.

The data took so long to process because originally scientists were not able to distinguish the OAWRS signals of smaller predators like cod from prey. However, some of the frequencies OAWRS uses are near the resonances for fish swim bladders, and advances in analysis allowed them to reassess the data and tell the fish apart.

“Fish have swim bladders that resonate like bells,” Makris explained. “Cod have large swim bladders that have a low resonance, like a Big Ben bell, whereas capelin have tiny swim bladders that resonate like the highest notes on a piano.”

The study is published open access in the journal Communications Biology.

Source Link: Largest Feeding Frenzy Ever Recorded Sees 10 Million Fish Eaten In Just A Few Hours