Two phase 3 trials of an Alzheimer’s drug have failed to demonstrate significant improvements in cognitive function, throwing doubt on one of the leading theories as to the cause of the neurodegenerative disease.

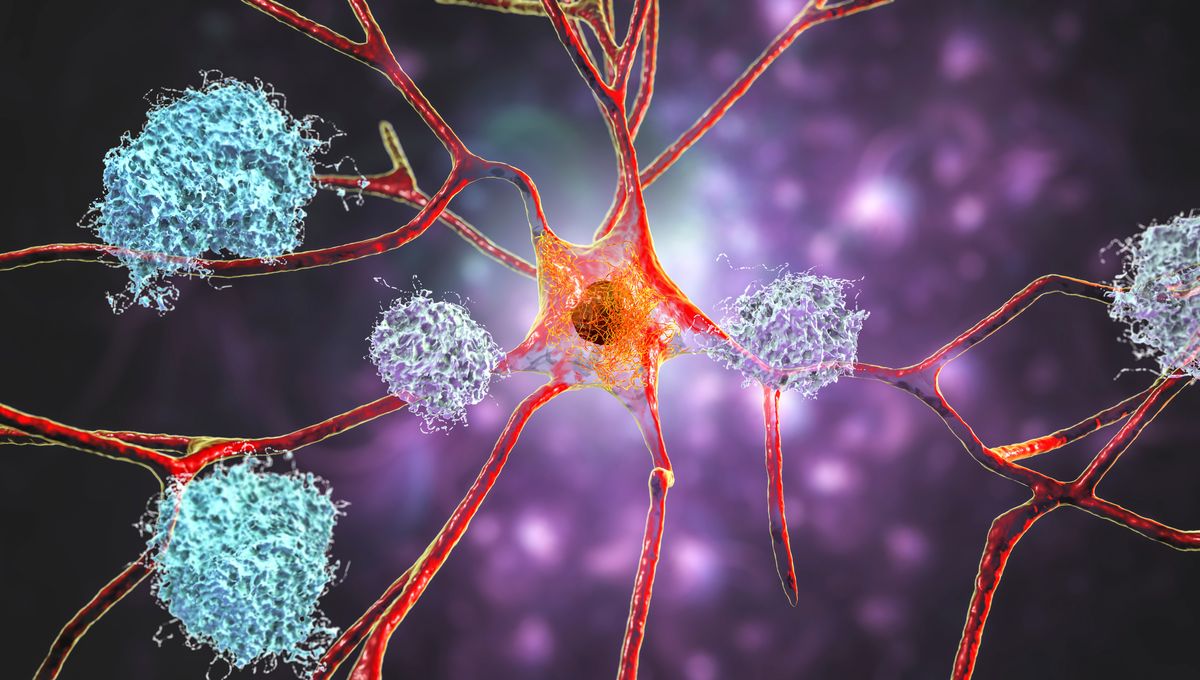

The so-called “amyloid hypothesis” proposes that build-up of a protein called amyloid-beta is responsible for the neuronal death and degeneration that is characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. More than a century ago, plaques of an unknown protein were discovered in the brain of someone who died with dementia. In 1984, the amyloid-beta protein was discovered and still to this day remains one of the key suspects in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis.

However, as these plaques are also present in the brains of many elderly people with normal cognition, and because the development of treatments had failed for many years to get off the ground, some have called into question the hypothesis’s validity. There were even claims of fabrication of evidence in a highly cited paper that supported the theory last year. And the two most recent trials don’t appear to lend credence to it either.

The trials, both of which involved almost 1,000 people, tested a drug called gantenerumab in people with early Alzheimer’s disease. While the monoclonal antibody treatment did lead to a lower amyloid plaque burden compared to a placebo, there was no sign of the improved cognitive function that you might expect to accompany this.

This is “surprising”, writes Lon Schneider in an accompanying editorial. Gantenerumab is similar to two other drugs, aducanumab and lecanemab, which have both been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease, Schneider explains. All three drugs contain synthetic antibodies that bind to amyloid-beta in the brain to help reduce plaques, although whether this translates to improvements in dementia symptoms is debated, especially in light of the latest findings.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either gantenerumab or a placebo once a fortnight for 116 weeks. To assess their dementia severity before and after the trials, the researchers used the Clinical Dementia Rating scale–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) – giving each a score between zero and 18, with higher scores indicating greater cognitive impairment.

After more than two years, there was no significant difference between the changes in CDR-SB scores of those on the drug or the placebo, demonstrating that in neither trial did gantenerumab significantly improve cognition.

“The gantenerumab trials add to the evidence of variable, small clinical effects of antiamyloid antibodies. Depending on one’s perspective, the results of the antibody trials to date either reinforce confidence in this therapeutic approach and its clinical meaningfulness or support a view that the effects are small, unreliable, and barely distinguishable from no effect,” concludes Schneider.

However, Schneider also notes some shortcomings of the trials, including risk of bias and inadequate masking of the drug and placebo, and suggests they may not have been long enough to see a real difference in Alzheimer’s symptoms.

“If a meaningful effect is not apparent after 1.5 to 2 years of treatment, there may be hope that it manifests in the future.”

After decades of research into the role of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis, it seems we’ll still have to wait to get a definitive answer.

“There is much we do not know about targeting amyloids in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and perhaps we will learn more from ongoing prevention or registry trials of antiamyloid antibodies in clinical practice,” says Schneider.

The results of the trials are published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Source Link: Leading Alzheimer's Theory Called Into Question As Another Drug Fails Trials