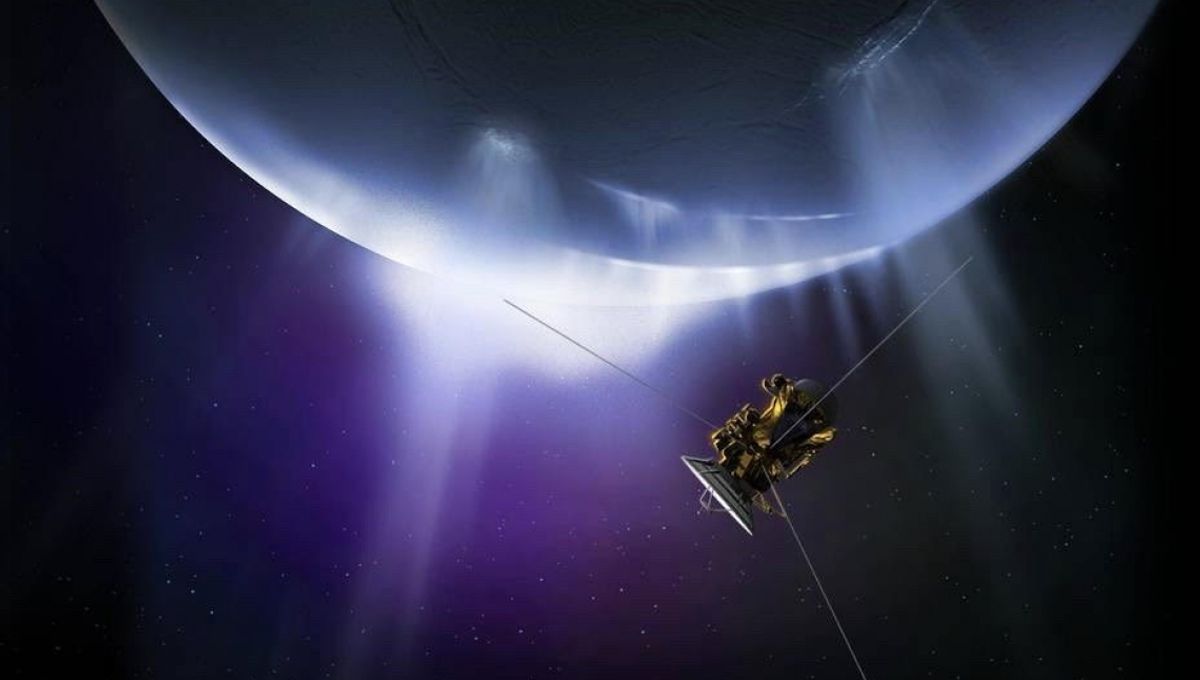

The Cassini mission has shown that Enceladus ticks several boxes when it comes to suitability for life. Under its thick icy exterior, the moon has a deep water ocean where hydrothermal vents are active. There’s plenty of water and energy in abundance. This might not be enough to sustain life, but researchers now propose a mission to confirm if life is indeed there – and it won’t even require landing on Enceladus.

The icy crust of the moon is between 5 and 30 kilometers (3.1 and 18.6 miles) thick, so the ocean is not easily accessible. Proposals envision landers that can drill through the ice and slowly go through the shell – something that appears to be a herculean undertaking. Enceladus releases water plumes into space through cracks in its surface, so a robot crawling through these cracks has also been suggested – another challenging approach, even without considering the troubles researchers would have to go through to make sure the craft is completely sterile.

Last year, researchers suggested that as long as the possibility of life in the universe is high, methane in the plumes could be a sign of life. In a new work, they go a step further. They estimate that even a small population of organisms on Enceladus would release enough organic material to be picked up by an orbital mission.

“We were surprised to find that the hypothetical abundance of cells would only amount to the biomass of one single whale in Enceladus’ global ocean,” the paper’s first author, Antonin Affholder, a postdoctoral research associate at UArizona, said in a statement. “Enceladus’ biosphere may be very sparse. And yet our models indicate that it would be productive enough to feed the plumes with just enough organic molecules or cells to be picked up by instruments onboard a future spacecraft.”

The mission’s main design would be not to find life but to disprove its presence. The work here estimates the maximum amount of organic material that could be found by such a spacecraft in the absence of life. Doing the opposite, collecting evidence for life, would be a laborious task.

To sample a cell-like material from a plume, the orbiting spacecraft would need about 0.1 milliliters of material. This is relatively small, but given how diffuse the plumes are, it would take more than 100 flybys of Enceladus – a high number, but hardly an impossible one. In the first four years of the mission, Cassini performed 74 unique orbits around Saturn and 45 flybys of Titan, the ringed planet’s largest moon. In total, Cassini spent 13 years in the system.

“By simulating the data that a more prepared and advanced orbiting spacecraft would gather from just the plumes alone, our team has now shown that this approach would be enough to confidently determine whether or not there is life within Enceladus’ ocean without actually having to probe the depths of the moon,” added Régis Ferrière, senior author of the new paper and associate professor in the UArizona “This is a thrilling perspective.”

It might take a long while before a mission happens to test this hypothesis, but it is very exciting that we might find life on Enceladus without landing there.

The work is published in The Planetary Science Journal.

Source Link: Life Could Be Found On Enceladus Without Actually Landing On It