One of the great joys as a child is learning about magnets, the seemingly magic objects that make metal fly away from the floor.

Modern magnets are commonly manufactured by taking ferromagnetic materials such as iron or nickel, heating it before subjecting it to a strong magnetic field, aligning the magnetic field in a uniform direction before compacting the material “freezes in” this alignment. But we knew about magnetism long before magnets were first manufactured in 1600 by physician William Gilbert thanks to “lodestone”, naturally magnetized pieces of magnetite.

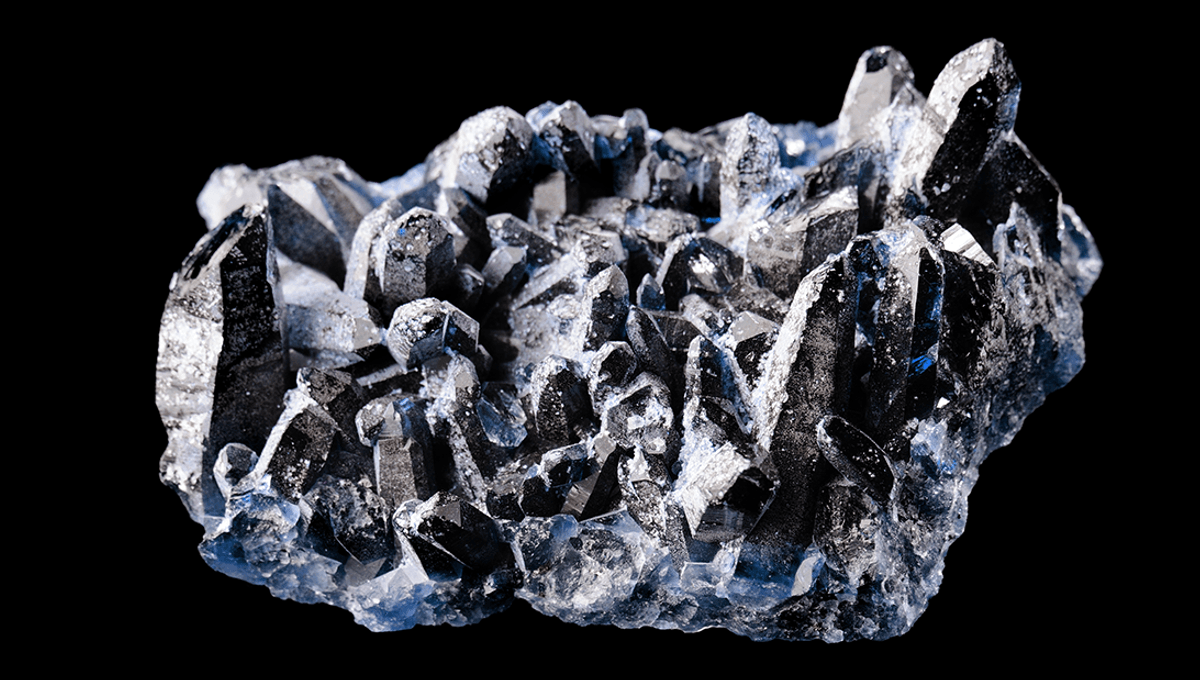

Magnetite, one of the most common types of ore, is attracted to magnets. However, in certain circumstances it can become naturally magnetized, creating the far rarer lodestone. An experiment on the top of South Baldy mountain near Socorro, New Mexico, using lightning rods to attract lightning to samples of magnetite showed that it did cause the stone to become magnetically charged, a likely explanation for how lodestone becomes magnetized in nature, and why it is found at the surface but not far below.

A compass made by shaping lodestone into the shape of a spoon.

Lodestone is mentioned by Roman philosopher and naturalist Pliny the Elder, who relays a legend of “Magnes the shepherd” who stumbled across it “and he is said to have found it when the nails of his shoes and the ferrule of his staff adhered to it, as he was pasturing his herds.”

This account was published in 77-79 CE, but humans have known about lodestone long before that. The first reference to the stone’s magnetic properties comes from 600 BCE, when Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus noticed that iron was attracted to it. References to magnetism also appear in a Chinese 4th century BCE book Book of the Devil Valley Master, though it would take until the 12th century CE before lodestone was used in the area to create a compass for navigation.

Source Link: Lodestone: How The Ancient World Learned About Magnetism