If someone you knew asked for rainbow crystals to be scattered on their grave at their funeral, you’d probably think they were channeling some New Age philosophy. According to a recent study, though, they may be doing the exact opposite – going back to their roots. About 6,000 years back, to be precise.

“It looked like glass, but then we noticed it was a different color. And we started to think, ‘Blimey, maybe this is something else’,” Nick Overton, a research associate in the School of Archaeology at the University of Manchester, UK, told Live Science.

He’s lead author of the study, published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal last month, which aims to explain exactly why rock crystal – this rare type of quartz that’s as clear as glass or water – is so often found in Neolithic sites around Britain and Ireland.

And to figure it out, Overton and his colleagues focused on one site in particular: Dorstone Hill, in Herefordshire, on the border between England and Wales.

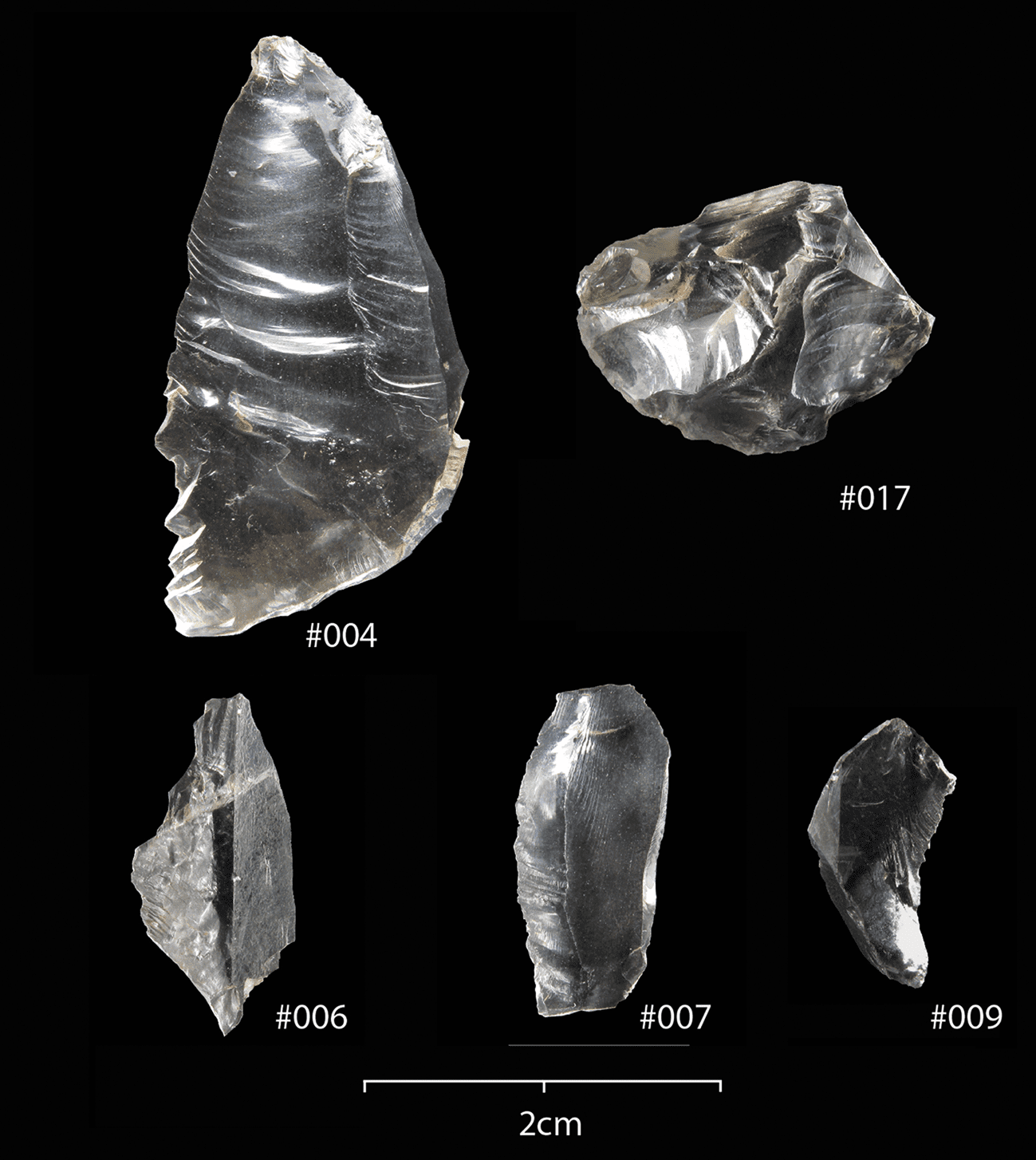

“Totalling 337 pieces, this is one of, if not the largest assemblage of worked rock crystal within Britain and Ireland,” the paper notes, “offering an important opportunity to examine the working, use and treatment of rock crystal within a British Neolithic context.”

Examples of larger pieces within the Dorstone Hill assemblage, including cores and pieces exhibiting crystal edges. Image: Overton et al., 2022

Dorstone Hill is home to the so-called “halls of the dead” – two gigantic ceremonial grave mounds, first discovered nearly a decade ago, which were likely created to memorialize on a grand scale the local community and leaders.

And that’s one clue as to why so much rock crystal has been found there, too. They may have been used in funerary practices, the researchers believe: “The distinctive and exotic character of rock crystal at Dorstone Hill would have made moments of working this material significant events,” the paper explains. “The technological and distribution evidence demonstrates that these events were undertaken in very specific ways, and deposition was almost always in mortuary contexts, with close association to the cremated remains of the dead.”

But what is that “distinctive and exotic character”? Well, imagine you’re a Stone Age tribesperson trying to find a way to honor your deceased community members, and you start working on an exotic crystal, brought to your settlement from up to 160 kilometers (100 miles) away. It looks as clear as water – but when you turn it a little to catch the light, it creates rainbows; you strike two shards together, and it exhibits triboluminescence: you see a quick flash of blue light appear where they touched.

You’d probably think it was something special, wouldn’t you? Maybe even magical? And you wouldn’t be alone. As the paper points out, Indigenous peoples from as far afield as Australia, the Amazon, and native tribes across North America have all ascribed spiritual or ceremonial significance to the stone thanks to its extraordinary properties.

And at Dorstone Hill, “it feels like they’re putting a lot of emphasis on the practice of working [the crystal]… people would have remembered it as being distinctive and different,” Overton told Live Science.

“It must have been an arresting experience – the material is quite rare and quite distinctive in this period where there is no glass and no other solid transparent material.”

That’s why, unlike the other chipped stone found at the site, the rock quartz hasn’t been found fashioned into tools – “the products, the flakes, the cores and the debitage, [would have been] equally significant, not as ‘waste’, but as important in their own right,” explains the paper.

So, while the new study has shed some light on why rock crystal has been found at Dorstone Hill, a new question has moved to the foreground: Why haven’t we noticed this before? Quartz has been found at other British and Irish burial sites from the same period, but has mostly been ignored until now – even though the stone’s rarity in the region means that the Neolithic people who put it there must have gone to some lengths to do so.

“Dorstone Hill is not an isolated example,” the study authors write. “[We have] a clear opportunity to explore the movements and connections of Neolithic groups in the west of Britain in the first centuries of the Neolithic.”

“Furthermore, given the role that rock crystal played in the mortuary practices and identity at Dorstone Hill, studies of the ways in which rock crystal was worked, used and deposited at other sites would provide a more detailed understanding of the roles this material played in people’s lives, and their local and regional identities during the start of the early Neolithic in Britain and Ireland,” they conclude.

Source Link: "Magical" Quartz Buried In "Halls Of The Dead" Finally Explained