Flint tool-makers often cut themselves in the course of their craft, but injuries that can today be easily treated with bandages and antibiotics would have often turned deadly in the Paleolithic era. Calculations of the danger show just how valuable tools must have been to make them worth the risk, and how precious each tool would have been once made.

Today, the production of flint blades, known as flintknapping, is a hobby some people undertake to test their skills and keep in touch with our ancestors. However, for millions of years – even before our species arose – it was the key to survival for a creature lacking strength, speed, or inbuilt armory compared to rivals.

The fact many people undertake flintknapping for fun might lead to assumptions it can’t be that dangerous, but according to a new paper, that’s only because of other tools developed far more recently.

Researchers conducted the first quantitative study of flintknapping injuries, taken by asking 173 hobbyists and experimental archaeologists 31 questions each. “People like to say, ‘You are going to cut yourself while learning to flint knap, even if you are an expert flintknapper,” first author of the study, current University of Tulsa graduate student Nicholas Gala who was studying at Kent State at the time of the study, said in a statement. “So we wanted to know how dangerous it actually is.”

It turns out the dangers have been greatly underestimated, with many people reporting literally cutting themselves to the bone, and even into it. Nor is it just hands that are at risk: One respondent somehow cut their ankle so badly with a flake they needed a tourniquet.

Thirty-five people (one in five respondents) had small flakes get into their eyes. Almost a quarter of the sample had sought medical assistance. As one guide to flintknapping ruefully notes, stones knapped to the desired sharpness; “Do not discriminate between cutting animal hide and human flesh.”

Nor were these injuries something that happened once or twice in a lifetime of knapping. An extraordinary 12.7 percent of the sample said they injured themselves every time they tried to make a blade, and another third did so often or very often. Three-quarters said it used to be worse while they were learning.

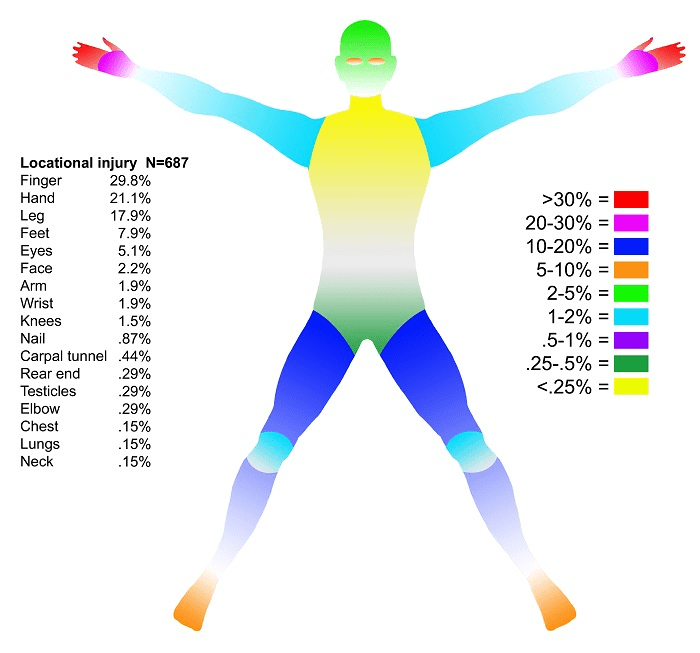

A body map shows the proportion of flintknappers that have injured body parts by color

Image Credit: Gala et al/Ancient Antiquities

Today, such injuries might make you question your choice of hobby, but can be patched with modern medicine. Pre-antibiotics, however, they would have come with a significant risk of infection that could get into the blood and turn lethal. That’s leaving aside other drawbacks, such as repetitive strain injuries and silicosis.

“This study emphasizes how important stone tools would have been to past peoples,” Eren said. “They literally would have risked life and limb to make stone tools […] But despite those injury costs, past peoples made stone tools anyway – the benefits provided must have been immense.”

At a time when life expectancy was around half today’s, the threat of starvation presumably loomed larger than a loss of sight or infection of the blood. Nevertheless, it’s unlikely humans ever weighed their lives so lightly as to not fear consequences this severe.

The dangers may have had the effect of bringing tribes closer together. “Social learning involves directly copying the outcomes or actions of a more skilled individual rather than learning everything by yourself through trial and error,” study author Dr Stephen Lycett of the University of Buffalo said. “We know from studies of animals and humans that social learning, rather than learning individually, is more likely when there is an increased risk or cost to learning alone.”

Flintknapping may have presented one of the most powerful drivers for people to spend long periods of time learning from mentors, tightening community bonds in the process.

2001: A Space Odyssey may have made it look like being taught to use weapons was a pure win for the apes who learned it – the downsides being ethical, not practical – but the truth was very different. Maybe there is a reason monkeys have been found using stone tools in many parts of the planet, but have not turned flintknapping into an industry the way our ancestors did.

The study is published open access in American Antiquity, but be warned, it contains some gruesome descriptions of flintknapping injuries.

Source Link: Making Flint Tools Came With Risk Of Life-Threatening Injuries For Ancient Humans