There are treasures to be found among the sediments of abyssal plains for those willing to dive 3,000–6,000 meters (9,800–19,600 feet) to go searching. Here, vast fields of manganese nodules can be found, rich in metals that would have battery makers’ eyes turning to dollar signs.

Sometimes referred to as deep-sea potatoes, or manganese tubers, these polymetallic lumps take millions of years to get to substantial sizes. They’re compared to potatoes because of their size and location either partially or completely buried in the seabed, but here their similarities end.

Manganese nodules are made up of four metals that are essential to making batteries – cobalt, copper, manganese, and nickel – as well as some iron, titanium, and trace amounts of rare-earth metals. At a time when sustainability goals are seeing a shift from petrol cars to electric, sourcing such materials is a hotter market than ever and some believe manganese nodules may represent a safer mining approach for accessing them.

Polymetallic nodules were first discovered on the seabed during the 1872–1876 voyage of the HMS Challenger to study the deep ocean. However, efforts to enroll them in industry have been stalled namely because they’re very difficult to get to at thousands of meters deep and there’s been little in the way of official governance over mining at this depth. However, that might be about to change.

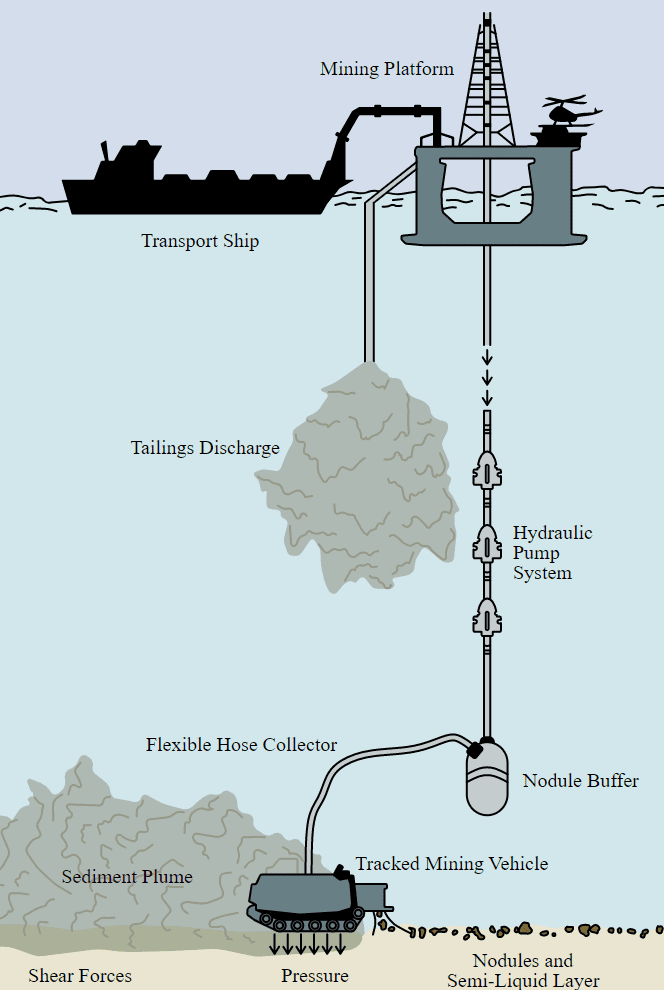

The Metals Company is one prospective deep-sea potato harvester, stating it plans “to lift polymetallic nodules to the surface, take them to shore, and process them with near-zero solid waste, no tailings or deforestation, and with careful attention not to harm the integrity of the deep-ocean ecosystem.”

Polymetallic nodules found on the seafloor contain considerable volumes of critical metals needed for building a sustainable future, and their fields can cover vast areas of the abyssal ocean floor. Mining them on the ocean floor might avoid some of the environmental issues that come with terrestrial activity, say R Hein et al., 2020, but stepping into the unknown is always something that should be done with caution.

In a 2019 article “Deep-Sea Dilemma,” Olive Heffernan warns of the risk of mass extinctions posed by mining a habitat that is the exclusive home to some of Earth’s marine animals, especially if it’s carried out before adequate research has been conducted. It includes the cautionary tale of ecologist Hjalmar Thiel, who ventured to a remote part of the Pacific Ocean known as the Clarion–Clipperton Zone in the 1970s and later conducted the largest experiment ever on the potential impacts of commercial deep-sea mining.

“Called DISCOL, the simple trial involved raking the centre of a roughly 11-square-kilometre [4-square-mile] plot in the Pacific Ocean with an 8-metre-wide [26-foot] implement called a plough harrow,” wrote Hefferman.

“The simulated mining created a plume of disturbed sediment that rained down and buried most of the study area, smothering creatures on the sea floor. The test revealed that the impacts of sea-bed mining reached further than anyone had imagined, but it did not actually extract any rocks from the sea bed, which itself would have destroyed even more marine life.”

Not a great first result, then, and things didn’t appear to improve much across the four visits researchers have made to the same area since.

“The site has never recovered. In the ploughed areas, which remain as visible today as they were 30 years ago, there’s been little return of characteristic animals such as sponges, soft corals and sea anemones. ‘The disturbance is much stronger and lasting much longer than we ever would have thought,’ says Thiel.”

Precious taters indeed, but what are the lasting effects of removing them from the environment? That’s something we’ll want to find out before it’s too late.

[H/T: MIT Technology Review]

Source Link: Manganese Tubers Are Precious Deep-Sea Potatoes That Battery Makers Lust After