An international team of researchers have been able to track the distribution of matter across the universe over its whole age. The work used the first light that shone freely in the universe, the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), to study the unseen matter of the cosmos and confirm that observations agree with our models.

Now, depending on how you look at it, our understanding of the universe is either pretty good or woefully limited. There is a theory called the Standard Model of Cosmology that has been very good at explaining what we see. That said, two crucial components in it are dark matter and dark energy and we haven’t got the darndest idea of what they are. Dark matter is a misnomer. It is not dark, it is invisible as it doesn’t interact with light, only gravity.

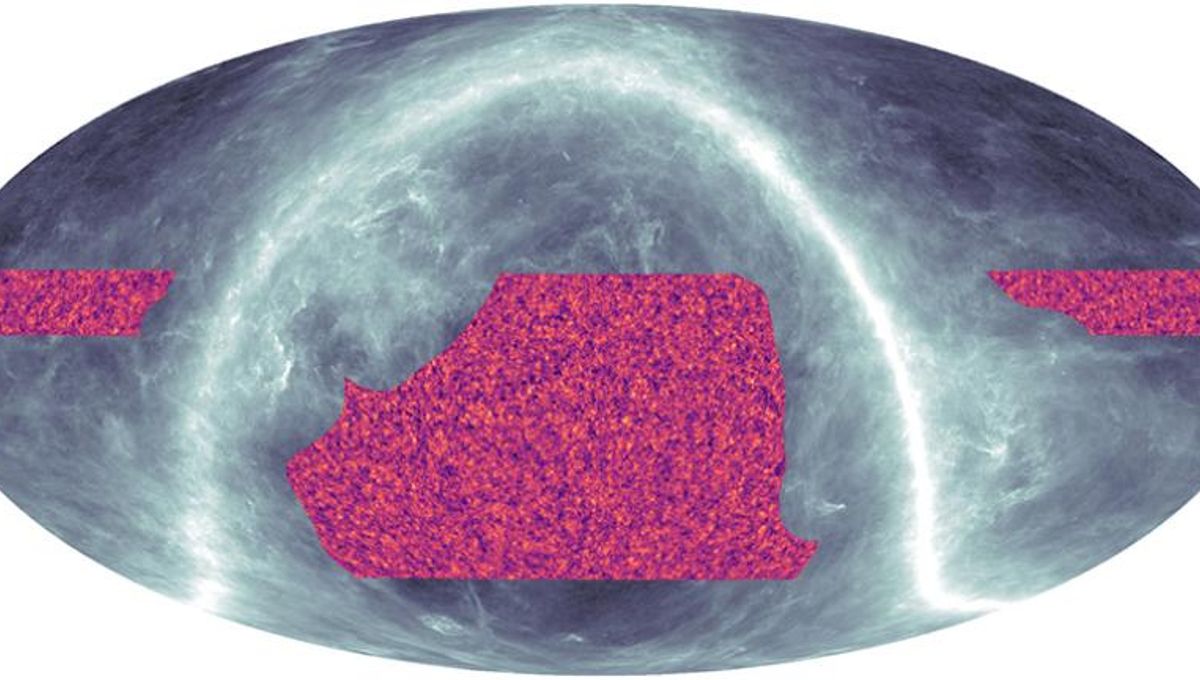

So the team used the Atacama Cosmology Telescope in the high Chilean Andes to observe subtle changes to the CMB due to massive structures such as galaxy clusters (filled with dark matter). The changes provide a map of the distribution of matter visible and invisible in the universe.

“We’ve made a new mass map using distortions of light left over from the Big Bang,” Mathew Madhavacheril from the University of Pennsylvania, lead author of one of the papers, said in a statement. “Remarkably, it provides measurements that show that both the ‘lumpiness’ of the universe and the rate at which it is growing after 14 billion years of evolution, are just what you’d expect from our standard model of cosmology based on Einstein’s theory of gravity.”

This is something to be very happy about. Despite the limits of our model, it continues to have great explanatory power. But there is a looming issue: the so-called Crisis in Cosmology. Different methods of measuring the expansion rate of the Universe get different results. In the context of the lumpiness, it might mean that dark matter was not as lumpy as expected. But the lumps from this map are exactly the right size.

“When I first saw them, our measurements were in such good agreement with the underlying theory that it took me a moment to process the results,” said Cambridge Ph.D. candidate Frank Qu, lead author of one of the new papers. “But we still don’t know what the dark matter is, so it will be interesting to see how this possible discrepancy between different measurements will be resolved.”

The papers have been submitted to The Astrophysical Journal and are available here.

Source Link: Map Of The Universe’s Growth Says Einstein’s Gravity Is Right – But A Major Issue Remains