Signs that Martian gravity is influencing the Earth’s climate have been found in sediments on the deep ocean floor. Long climatic cycles triggered by resonance between the two planets’ orbits have been predicted by models, but geologic evidence has been sparse. The scientists who spotted this pattern are wary of leaping to conclusions, but say it might mean there is less danger to the deep oceans from humanity’s climate vandalism than had been feared.

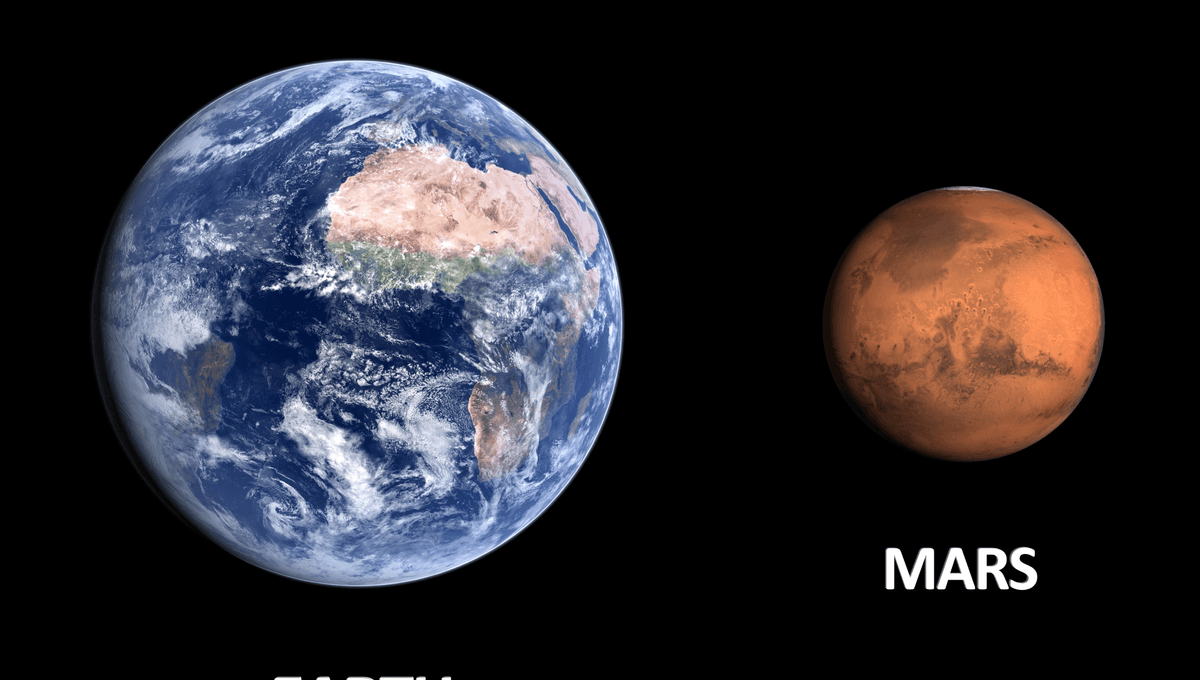

Mars is a small planet, and even though it’s relatively close, its gravitational effects on Earth are small. Over a long time, small things can become important, however. “The gravity fields of the planets in the Solar System interfere with each other and this interaction, called a resonance, changes planetary eccentricity, a measure of how close to circular their orbits are,” said Professor Dietmar Müller of the University of Sydney in a statement.

These changes mean that over a 2.4-million-year cycle, the Earth experiences periods of increased and decreased sunlight, similar to those produced by the much shorter Milankovich cycles. Although the changes in sunlight the Earth received over these cycles are subtle, Müller told IFLScience that amplifying factors are expected to lead to the planet warming and cooling significantly on this timescale.

Detecting such cycles is difficult when there are so many other drivers of global and local climates, and few examples have been found in the geologic record. However, Müller and colleagues have found a cycle in the deep oceans that matches the predicted timescale well. On the ocean floor, they found gaps, known as hiatuses, when sediment stopped building up, and these occur with a 2.4-million-year period.

Müller and colleagues say the hiatuses are a result of the strengthening of eddies in the deep ocean, which scour the sea floor so sediments can’t build up. The eddies are driven by winds. Warmer periods put more energy into the atmosphere, which strengthens the winds and gives the eddies enough power to scour the ocean floor clean, the team suspect, and all because of tiny forces from Mars.

If the authors are right, it might be a rare piece of good news for the planet’s future. If warmer conditions make for more powerful eddies, the extra heat humanity’s gasses are trapping could cause a similar enhancement. “There are signs this is already happening,” Müller told IFLScience, with wind-driven currents apparently strengthening, most notably the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

That would be welcome because one feared consequence of higher temperatures is a stagnant deep ocean. Without any force to stir it, the oceans would tend to stratify, with oxygen-rich waters at the top and colder waters confined to the depths. The eddies Müller and colleagues are investigating are one of the two main forces that prevent this happening. The other, known as the global thermohaline system or the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), works in very different ways, and is suspected of weakening as a result of decreased Arctic sea ice formation.

The AMOC is sometimes described as the offramp for the Gulf Stream.

If AMOC were to get weaker, let alone collapse as is feared, the increased stratification could have several disastrous consequences. For one thing, it would hinder the capacity of the oceans to draw carbon dioxide down into the depths where it does little harm. The loss of oxygen in deep water could also extend the global extinction event to the one region we might expect to be safe. Rising cold waters bring nutrients with them, creating the most fertile fishing grounds on Earth, and this could stop too. Finally, the global thermohaline system redistributes heat around the planet, and without it, some areas would warm even faster.

Müller’s eddies could counteract at least the first three of these, although Müller admitted to IFLScience that how fast and to what extent are questions beyond the scope of this research. “Of course, this would not have the same effect as AMOC in terms of transporting water masses from low to high latitudes and vice-versa,” he acknowledged in the statement.

Earth being more massive than Mars, our planet’s gravity should have an even larger effect on the Red Planet’s orbit. Müller told IFLScience he does not know what climatic effects this could have produced there, and whether we could find any evidence of it.

The study is open access in Nature Communications.

Source Link: Mars's Gravity May Be Strong Enough To Influence Earth's Deep Ocean Currents