When people think back to the time of the dinosaurs, most people picture a giant Tyrannosaurus rex or a majestic sauropod roaming through our prehistoric planet. Mammals on the other hand, though around at the time of the dinosaurs, remained small and rarely weighed over 10 kilograms (22 pounds). However, 20 million years after the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event that wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs, mammals weighing more than 1 tonne were abundant throughout the landscape. So how did they get to be so big?

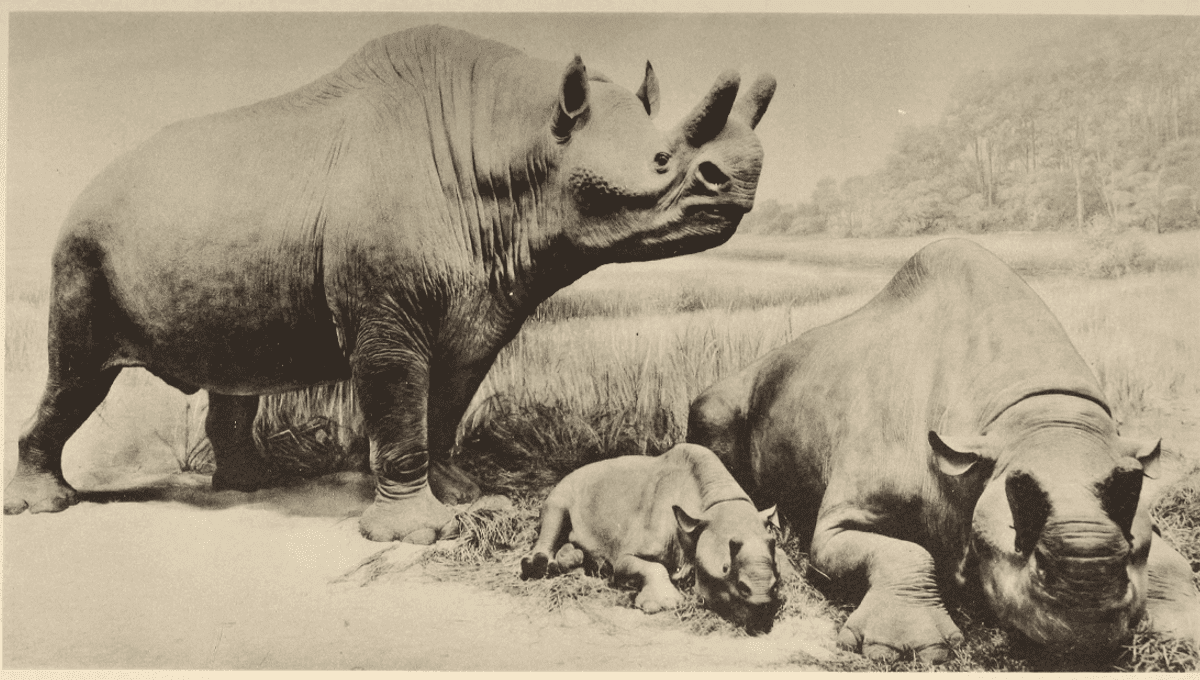

Several ideas about how Cenozoic mammals evolved to have huge multi-tonne bodies have been explored. By using brontotheres – mammals that look like modern-day rhinos but are actually more closely related to horses – a team of researchers has been exploring the likely different pathways that lead to mammalian supersizing.

Brontotheres were chosen because they experienced one of the most extreme size increases seen in these early mammals and are well preserved in the fossil record. The first known brontotheres were thought to be around 18 kilograms (39 pounds) in size, yet in their 22-million-year history more than half of the 57 species belonging to this group had an estimated weight of over 1 tonne.

Three scenarios that might explain this rapid increase in size were tested. The first was that steady size increases happened through the lineages; the second suggested that these brontotheres developed a larger body size as an adjustment to successive adaptive zones; and the third idea is that speciational evolution occurred without preferential direction.

After performing modeling tests on a dataset of 276 brontothere fossils, the team suggest that the model where body size change mainly occurs at speciation events without a preferential direction is four times more likely than the two other scenarios. However they suggest that just this idea alone does not fully account for the jump in brontotheres from being around 20 kilograms (44 pounds) to more than 3 tonnes.

The team propose that the ecological niches in which the herbivorous brontotheres lived became saturated, explaining the diverse range of sizes within these ancient mammals. The smaller brontotheres that lived in these highly competitive niches evolved to be bigger to combat the higher extinction risk they experienced.

The team suggest that further modeling research into climate and niches would shed light on whether environmental change led to the demise of the brontotheres as their overall lineage survival decreased in the second half of their history.

The study is published in Science.

Source Link: Massive Rhinoceros-Like “Thunder Beasts” Evolved Huge Body Sizes To Survive