The big picture of Earth’s geologic history over the last 2 billion years is of continents coming together and then breaking apart every 600 million years or so. A future rejoining is inevitable, but geologists have long debated whether it will occur when the Americas’ west coasts run into Asia, or if their east coasts will recombine with Europe and Africa. A new study concludes fundamental changes have occurred deep within the Earth, so only the former scenario is now possible.

A joining of the continents leaves most of the world to be taken up with a single vast ocean, the occasional island aside. During the time of Pangea, the last universal supercontinent, this was known as Panthalassa. Once the continents start to break up, the world has two or more great bodies of water – internal ones surrounded by the spreading landmasses, and an external one the continents are moving into. The Atlantic and Indian oceans are the remnants of previous internal seas, while the Pacific is what became of Panthalassa, via the external ocean.

New supercontinents can form by the closure of either the internal or external oceans. At least that is what Professor Zheng-Xiang Li of Curtin University argues has been possible in the past. Now, however, the Earth has reached a point where only external oceans can close, Li and co-authors conclude in research published in National Science Review, making the Pacific’s demise inevitable.

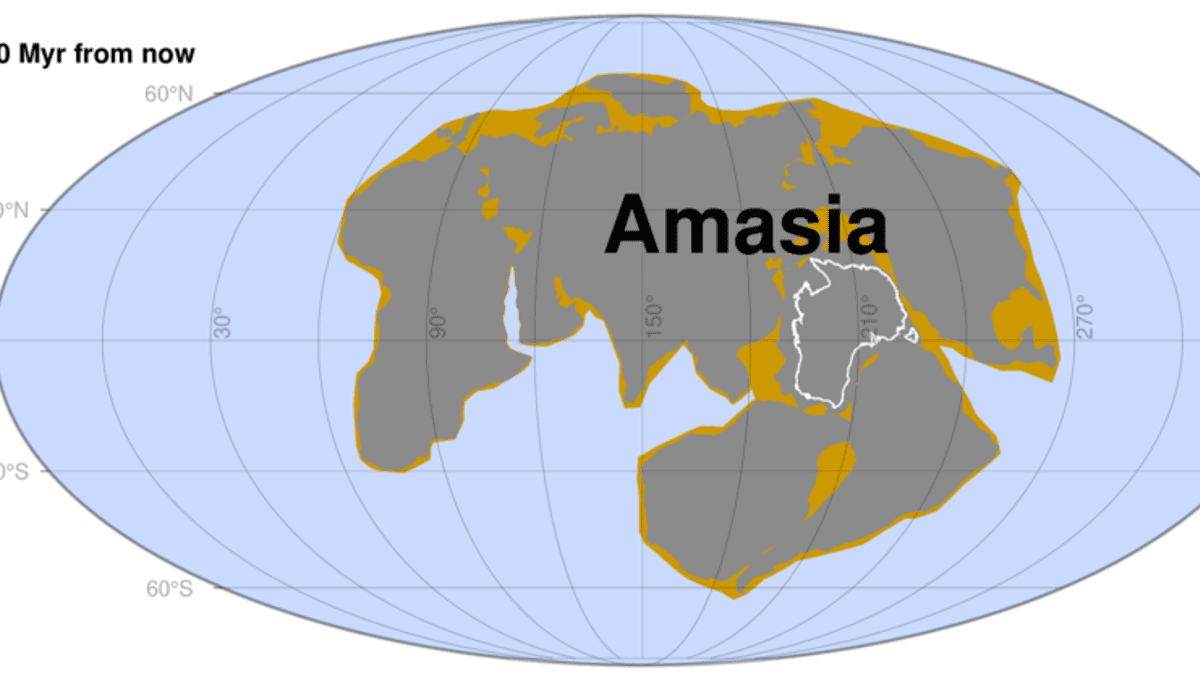

The Atlantic is currently growing at a rate of a few centimeters a year, while the Pacific is shrinking at a similar speed, so it’s easy to extrapolate the closure of what is now the world’s largest ocean basin. Geologists have done this previously, naming it Amasia, which, Li told IFLScience, will take 280 million years to form from the pieces of Pangea at current rates. However, in the past such trends have sometimes reversed, with the continents coming back together, concertina-like, to reclose the internal ocean.

That, the paper claims, is no longer possible. The authors’ modeling suggests continental movements depend heavily on the strength of the oceanic crust between them. Only when the crust is strong can continents change direction and reunite across young internal oceans.

Counterintuitively, as the mantle has cooled, the oceanic crust forming atop it has become thinner and therefore weaker. Li and co-authors found that around 540 million years ago, the Earth’s temperature cooled enough that the crust weakened to a point where reversals like this can no longer take place. Therefore Amasia – and indeed all future supercontinents – will be formed by passage across the external ocean.

Along with the Americas’ westward march and Asia’s eastward migration, Australia will move north until it collides with Indonesia and is carried into what is now the South Pacific.

Antarctica has long been anchored at the bottom of the world, but Li told IFLScience its future movements are “hard to tell”. Nevertheless, he considers it most likely it will also move into the Pacific, adding that a zone it can shift into “already seems to be forming towards New Zealand.”

Some previous predictions have suggested Amasia would come together around the North Pole, creating an enormous ice cap and cooling the planet. However, Li told IFLScience, the larger continents’ latitudes are unlikely to change. That doesn’t mean the Earth will remain as hospitable as it has been during our evolution.

“Earth as we know it will be drastically different when Amasia forms. The sea level is expected to be lower, and the vast interior of the supercontinent will be very arid with high daily temperature ranges,” Li said in a statement.

The work is published in National Science Review.

Source Link: Meet The World’s Next Supercontinent, Amasia