More than a hundred volcanoes lie beneath the Antarctic ice, and the release of some of the weight upon them could spur them into life. According to a new study, the danger of this depends on the rate at which their icy burden lightens.

Human-induced hotter temperatures are making a variety of natural disasters worse – definitely fires, floods, droughts, and heatwaves, and possibly also hurricanes and even sudden cold snaps. At least earthquakes and volcanoes are safe, right? After all, these are driven by forces deep within the Earth, unrelated to our puny activities on top. Well most of the time perhaps, but not always.

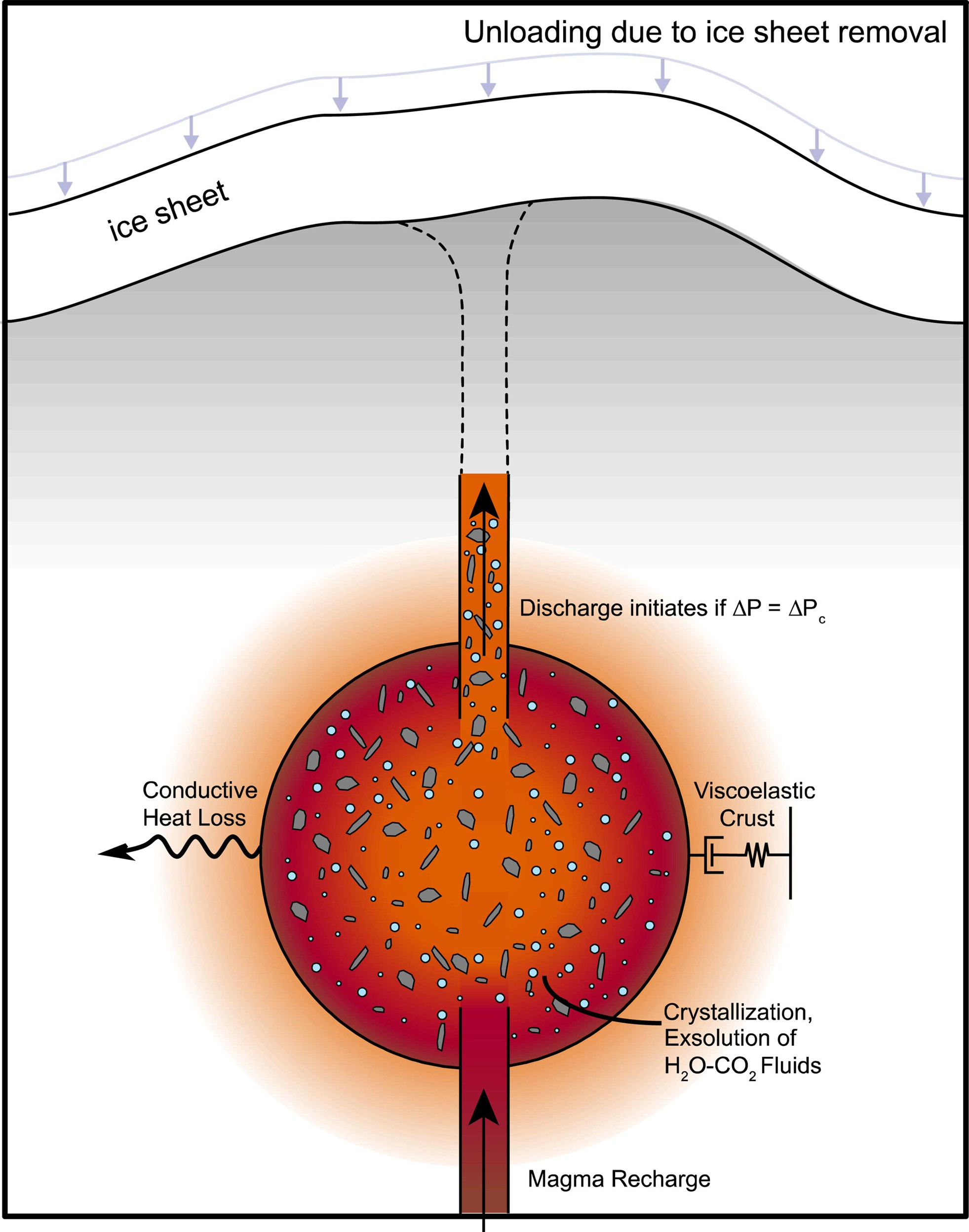

The ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland are so thick that their weight can significantly compress the ground beneath. Some regions are still rebounding after their glacial cover disappeared 10,000 years ago. That much pressure will affect the behavior of magma in chambers far below. However, as a new paper exploring the topic notes, “The effects of ice loss above volcanoes on the underlying volcanic activity are not well understood.”

Evidence that deglaciation of the Patagonian Ice Sheet triggered an increase in volcanic activity at the end of the last ice age aroused concerns this might happen again. However, when IFLScience explored the question late last year, there were hints of danger, but scientists expressed their uncertainty and the difficulty of research in the area.

Changing pressure, whether rising or falling, can cause ruptures in the Earth’s crust, through which magma can escape, particularly from shallow chambers. Moreover, below a certain downward pressure, water and carbon dioxide dissolved in the magma form bubbles, which raise the pressure within the magma itself, which can spark eruptions. However, while acknowledging the possibility, most volcanologists remained cautious about how much ice would need to melt to trigger such effects, and how likely this might be.

It’s hard to conduct practical experiments on something like this, given the forces involved, and experiments that may trigger volcanoes tend to annoy the neighbors. Instead, a team led by Brown University PhD student Allie Coonin turned to computer modeling of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), and the extensive volcanoes beneath. Although the WAIS is far smaller than its eastern counterpart, it’s more heavily studied because it is considered more vulnerable to collapse – “yet its position atop an active volcanic rift is seldom considered,” Coonin and colleagues write.

Beneath WAIS is the West Antarctic Rift System (WARS), one of the largest volcanic provinces on the planet, which began forming around the time things went bad for the dinosaurs. The authors point to previously published evidence the rift remains active.

Naturally there is a lot we don’t know about such an inaccessible province, but the authors modeled typical magma chambers using the known properties of basalt from the region, and assumed the presence of water and carbon dioxide.

As ice melts the authors found the associated pressure decrease in the magma chamber could lead to eruptions, but they add that “we demonstrate that the rate of unloading influences the cumulative mass erupted and consequently the heat released into the ice.” Things really get bad when the rate at which ice load decreases matches other important volcanic features, such as the recharge rate of magma in a chamber.

For example, if an ice sheet 1-kilometer thick (0.6 miles) melts in 300 years rather than 3,000, an extra 50 million tons of material escapes, the models suggest. Naturally, amounts that would have been released anyway erupt a lot faster.

Even a slow rate of melting will contribute to more eruptions, however. Indeed, the authors state, “Even if modern anthropogenic warming were curtailed immediately, the unloading that WARS subglacial volcanoes already experienced will still affect their behavior for hundreds to thousands of years to follow.”

Schematic representation of the model put forward in the study. The transparent arrows indicate unloading as ice melts over time, decreasing the thickness of the ice sheet.

Any increase in activity will release heat as well as lava and ash, which will cause the ice sheet to warm from below as well as up top and where it meets the ocean, causing still more melting. The authors anticipate around 3 million cubic meters of ice (100 million cubic feet) melting as a result of the additional heat released by a single typical magma chamber. This, of course, will set off more eruptions, and the cycle continues. The number of such chambers in the WARS is unknown, but thought to be about a hundred.

This, the authors add, is without considering the faster rate at which ice slides into the ocean if it melts at the bottom, reducing friction.

The study is published open access in Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems.

[H/T: Phys.org]

Source Link: Melting Ice Sheets Likely To Trigger Antarctic Volcanic Eruptions