Despite being the closest planet to Earth, and all other planets in the Solar System, in fact, Mercury gets little in the way of attention.

It only has itself to blame, being an inhospitable scorched planet with temperatures reaching 430°C (800°F) in the 59-Earth-day-long Mercury daytime. Even ignoring its lack of atmosphere, it’s not exactly the planet you want to one day visit.

But it is, nevertheless, pretty interesting. Back in 1974, for instance, NASA’s Mariner 10 mission flew by the planet and discovered evidence that it was shrinking.

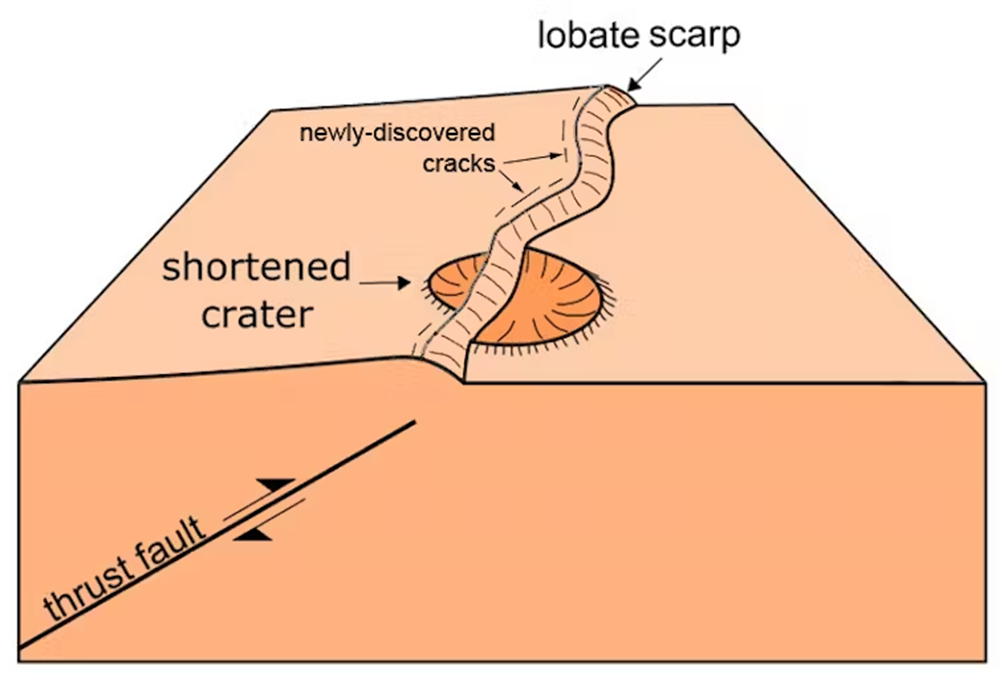

This evidence came in the form of kilometers-high slopes known as “scarps” all across the planet. These are caused by faults beneath the scarps called “thrusts” as the planet contracts due to thermal cooling.

“Because Mercury’s interior is shrinking, its surface (crust) has progressively less area to cover. It responds to this by developing ‘thrust faults’ – where one tract of terrain gets pushed over the adjacent terrain,” David Rothery, Professor of Planetary Geosciences at the Open University and author on a new paper exploring the planet’s contraction, explained in a piece for The Conversation. “This is like the wrinkles that form on an apple as it ages, except that an apple shrinks because it is drying out whereas Mercury shrinks because of thermal contraction of its interior.”

Shortened craters are a sign of the planet’s contraction.

In 2014 it was estimated that the planet had contracted around 7 kilometers (4.4 miles). On Mercury, we can get a pretty good idea of when this shrinking happened by looking at the many impact craters that cover its surface. While some of the craters have become shortened by the planet’s contraction (shown in the above diagram) there are also craters on top of scarps, meaning that the impact that caused them happened after the fault shifted the planet’s crust.

From this, astronomers concluded the scarps were around 3 billion years old. In the new study, however, the team found evidence that the planet’s contraction isn’t over yet, as Mercury continues to cool down.

On scarps, Open University PhD student Ben Man found “grabens”, where land had fallen down in between two faults, and a sign of stretching.

“Stretching may seem surprising on Mercury, where overall the crust is being compressed,” Rothery explained, “but Man realised that these grabens would occur if a thrust slice of crust has been bent as it is pushed over the adjacent terrain. If you try to bend a piece of toast, it may crack in a similar way.”

As these grabens had not been entirely covered by debris from impacts on the Mercury, the team was able to estimate that the stretching and collapsing took place less than 300 million years ago, evidence that the contraction of the planet is still taking place today.

The study is published in Nature Geoscience.

Source Link: Mercury Appears To Be Shrinking