A woman depicted in the section of the Sistine Chapel relating to Noah’s flood has one healthy breast and one showing signs of disease. A forensic pathologist has teamed up with doctors and art experts to diagnose the fictitious woman five centuries after one of history’s most revered works was painted. Although modern medicine arrived far too late to treat those Michelangelo may have seen with the disease, perhaps recognition may encourage viewers to get checked.

In the 16th century, the capacity to represent the human form accurately was highly prized, and this did not just include representations of ideals, such as Michelangelo Buonarroti’s other most famous work, David. The Sistine Chapel frescoes include images of people in all stages of life, including signs of disease.

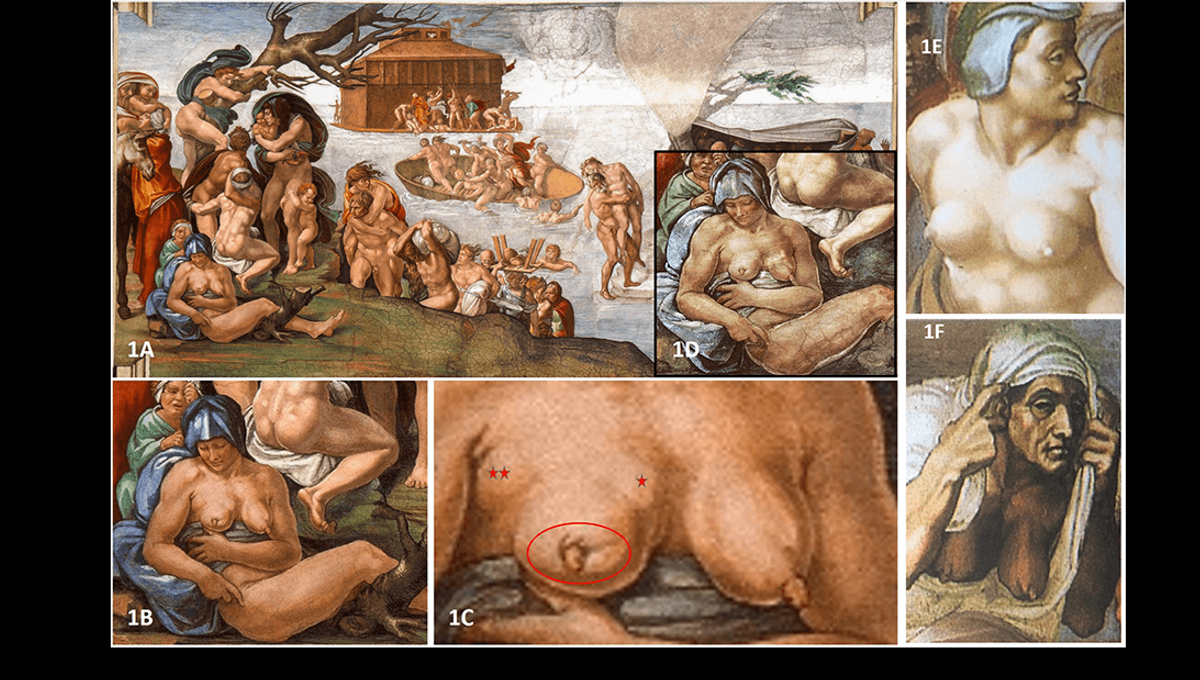

The differences between the two breasts of one woman at the front of the Sistine Chapel fresco The Flood are obvious enough to have clearly been deliberate, even if the work had been by a lesser artist. As part of an expanding discipline known as iconodiagnosis, Professor Andreas Nerlich of Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich has sought to identify the disease affecting the unfortunate woman’s right breast.

The Flood was among the first of the Biblical frescoes Michelangelo posted on the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling. As Noah’s ark floats in the background, the doomed rest of humanity flees the rising waters. Although it has not become anything like as famous as his Creation of Adam, it forms an important part of one of the most famous artworks of all time.

With so many mostly naked figures present, many may have over- (or should we say under-) looked a single breast. But in Renaissance painting there was usually a meaning to everything. The woman’s blue headscarf, for example, indicated to viewers of the day that she was married, and her healthy left breast’s shape indicates she suckled a child. It’s unlikely the form of the right breast was a whim.

Nerlich and coauthors propose the two lumps visible in the upper part of the breast represent enlarged nodes, and the retracted skin of the areola is also indicative of disease. However, they think a slight discoloration on one side of the breast is an artistic effect, rather than a symptom.

Renaissance Europe was prey to many diseases the rich world has largely banished, such as tuberculosis. The authors note the resemblance of the image to the nodular form of tuberculosis mastitis, but conclude this would have been rare even then, while other possibilities do not match the age of the woman and her weeping child.

Consequently, they argue, by far the most likely condition Michelangelo would have encountered that produced visible symptoms like this would have been a carcinoma of the breast.

Another artist might have been faithfully portraying the breast of a model, but the authors note, “Michelangelo did not resort to a living model (or living models either male or female) when depicting the story of the Genesis. No realistic portraits are presented in the scene.” On the other hand, he had assisted with autopsies at age 17 to learn anatomy, and the diseases he saw influenced him. In-keeping with lingering Medieval practice, sinners in art were marked by illness, deformities, or distorted expressions.

Some of the figures in The Flood are considered to be representations of the seven deadly sins, but it is less clear whether the afflicted woman belongs to this group, perhaps as lust.

Despite those who want to attribute all cancers to modern lifestyles, the disease has been with us at least since the Triassic, although until recently it was overshadowed as a cause of death by infectious diseases.

Although breast cancer most often occurs among women older than the one depicted in the scene, the BRCA1 gene can often trigger it at younger ages. BRCA1 has been traced to the Tuscany region, where Michelangelo was born, starting 1,300 years before the painting.

Fourteen years later, Michelangelo again may have depicted breast cancer in his sculpture The Night, but the authors of this paper think his symbolic meaning was different, referring to “fate, not punishment”.

The study is published open access in The Breast.

Source Link: Michelangelo May Have Painted An Unusual Cancer Case In The Sistine Chapel