The Grotte Mandrin cave has overturned anthropological thinking about the arrival of Homo sapiens in Western Europe. A new paper attempts to build a new picture that puts the Mandrin discoveries in context of human activity in Asia. The author concludes modern humans arrived in three waves, only displacing the Neanderthals with the third.

Until last year it was thought H. sapiens didn’t reach Western Europe until 43,000 years ago, and all cultural artifacts from before that time must be the work of Neanderthals. The discovery of a child’s tooth at the cave in the Rhône Valley, France, disproved that idea. However, the same dig revealed teeth from six different Neanderthals in the cave, some in more recent layers than 54,000 year-old deposit where the human tooth was found.

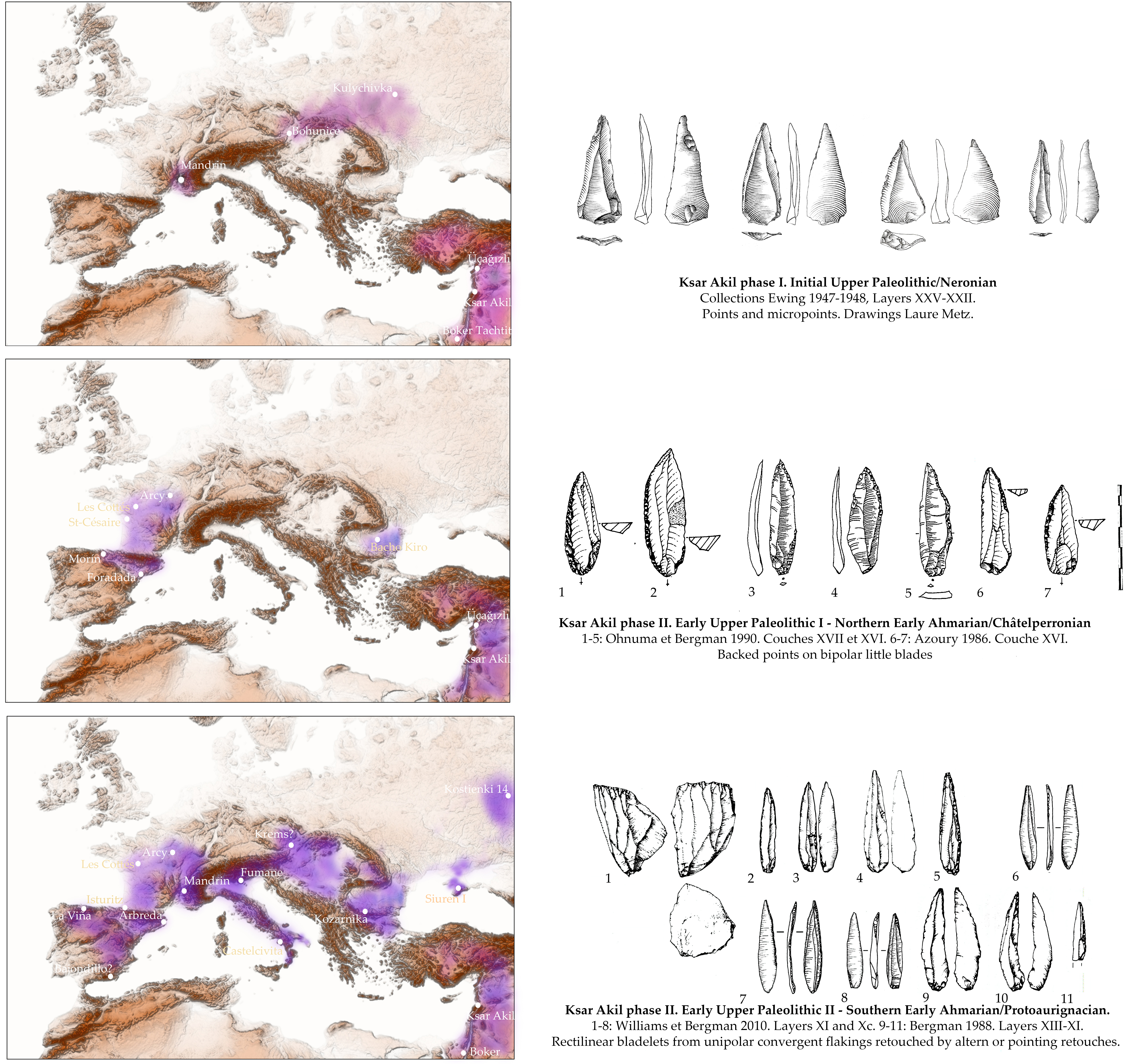

More recently, hundreds of artifacts, including bows and arrows, have been reported in Mandrin’s Layer E, where the crucial tooth was found, representing the largest known collection of so-called Neronian items. These have offered us some insight into the first H. sapiens to occupy Mandrin, but the subsequent long absence of Sapiens from the record left things looking very murky. In the new paper, Dr Ludovic Slimak of the Universite de Toulouse III has attempted to clear that up by comparing the style of tools found in Mandrin in and above Layer E with those found at Ksar Akil, Lebanon.

When the first sapiens arrived at Mandrin, Neanderthals had occupied the cave at most a year before. Whether they left peacefully or were displaced through violence, we may never know. It’s certainly possible that this was one of the times Neanderthal DNA got into our genome, so the two peoples may have shared accommodation as well as bodily fluids. However, it seems like the first H. sapiens arrivals in the area did not stay. No evidence of their presence has been found at other sites that far back, and soon afterward Mandrin was home to Neanderthals again.

When H. sapiens returned to the area their toolmaking had changed. Slimak argues that the technologies seen in Western Europe are “precise technological and chronological counterparts” of those found at Ksar Akil. If so, it seems that H. sapiens, having established a large presence in what is now the Middle East, developed new toolmaking styles, which then swept into Europe.

Ksar Akil is an outstandingly rich resource; almost 18,000 artifacts have been found there, providing detailed tracking of humanity’s technological development over thousands of years. Slimak argues the Neronian style found at Mandrin and elsewhere in the Rhone Valley “technically represents a perfect replica of the Levantine phase” from Ksar Akil.

Slimak draws a similar link between later styles of toolmaking from Ksar Akil and the Western European cultures known as the Châtelperronian and Protoaurignacian. Back when all travel was on foot, passage between the two took generations. Nevertheless, Slimak claims; “No distinction can be made here between these technical systems, even though they are located at opposite ends of the Mediterranean.” Slimak even suggests the immigrants may have taken shortcuts over water.

In this chronology Neanderthals reclaimed the territory after the first, abortive, wave. They probably co-existed with H. sapiens through the second before being overwhelmed by the third.

Slimak’s reasoning is based on features such as the shape of points on spearheads and cutting tools. There is inherent subjectivity in weighing the similarities and differences of such items, and Slimak’s interpretation contradicts conclusions other anthropologists have reached about the relationship between Paleolithic technologies.

In particular, Châtelperronian tools are usually considered to be the work of Neanderthals, not H. sapiens. Yet the makers of the style Slimak considers equivalent at Ksar Akil were definitely members of our species. Consequently, the claims are likely to spark furious debate, as is so common in palaeoanthropology.

The study is published open access in PLOS ONE.

Source Link: Modern Humans Reached Europe In 3 Waves Starting 10,000 Years Before Previous Estimates