It may sound like the lair of a Bond villain, but at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, an instrument is being built to detect neutrinos. Before the vast majority of the detector has been built, its construction has been vindicated with the announcement of an ultra-high-energy neutrino, probably the most energetic ever detected.

Neutrinos are a triumph of theoretical physics. When certain sub-atomic interactions appeared to end up with less energy out than in, physicists knew this violated the law of conservation of energy. The solution they proposed was that there was another particle, exceptionally hard to detect, that was carrying away the missing energy either at the speed of light or very close to it. These were named neutrinos, and vast detectors have been built deep in old mines and in the ice at the south pole to find them, proving their existence and that their speed is not quite equal to light.

Neutrinos are staggeringly abundant in the universe, but they interact with matter very seldom, so trillions of them stream through your body every second without you noticing. When we can catch them, however, they tell us a great deal about the inner workings of the universe’s great explosions, beginning with 1987a, the last supernova in our local group of galaxies.

Since it is their capacity to carry energy that made us care about neutrinos, it’s not surprising that the most energetic ones particularly interest us. Ultra-high-energy neutrinos (those over 0.5 peta electron volts) have been a recent discovery, providing another window into the most powerful events in the universe.

At the Neutrino 2024 conference, held in Milan last week purely to discuss new developments in neutrino science, attendees heard about neutrinos from the Sun, supernovae, and cosmological sources, as well as those from human-made reactions.

Dr João Coelho of the French AstroParticle and Cosmology Laboratory gave a talk on the progress of ARCA, the Astroparticle Research with Cosmics in the Abyss observatory, being built 3,500 meters (11,500 feet) beneath the sea off Sicily.

Coelho ended his talk with a report on ARCA’s most exciting observation so far. Nature reports he said this one “really stands out, very far away from anything else.” Ultra-high energy neutrinos are not only thought to be much rarer than their less energetic counterparts, they’re also much harder to detect and distinguish from other particles.

Coelho wasn’t giving a lot away, saying the timing and direction of the neutrino would be published in good time. In doing so, he left his fellow particle physicists on tenterhooks, waiting to find out if a clear source for the neutrino can be identified. He did, however, reveal that the instrument picked up three large depositions of energy along the track of its muon daughter particle. More light was detected from this event than in simulations of a 10 peta electron volt neutrino, indicating the source was probably several times more powerful than that.

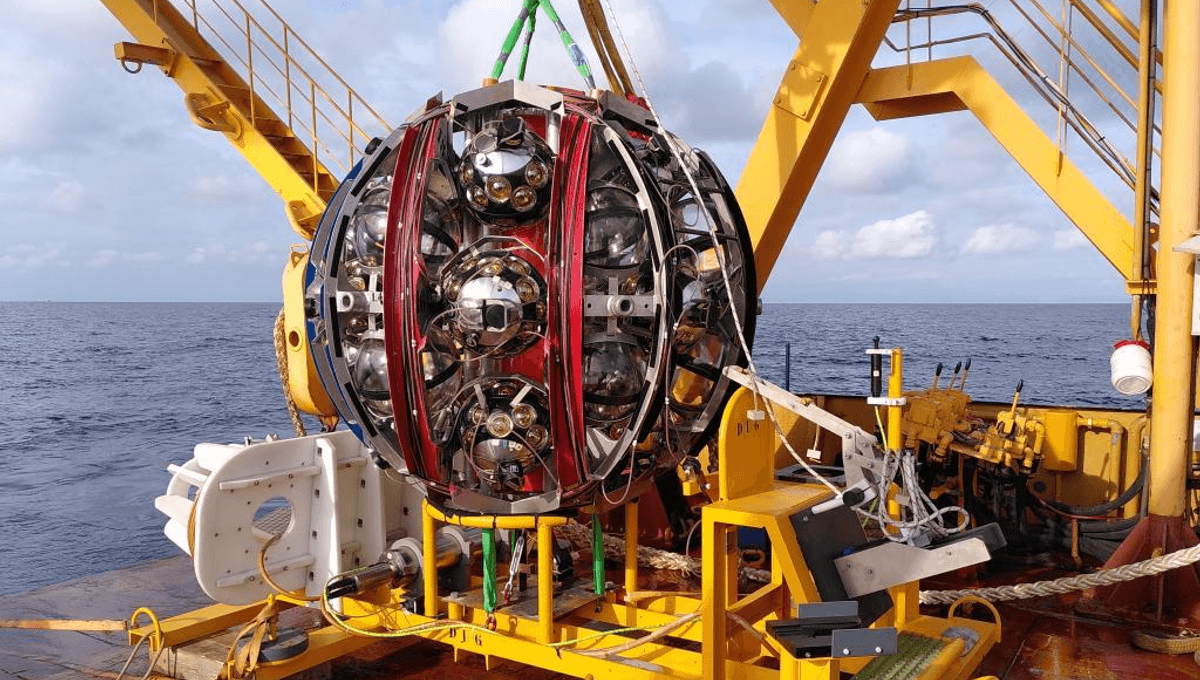

ARCA is composed of 800-meter (2,600-foot) long strings that sit on the ocean floor, dotted with detector units composed of spheres sensitive enough to detect just a few photons.

When energetic cosmic rays hit the atmosphere they produce showers of subatomic particles, which leave flashes of light when they pass through water. Close to the surface, this light is overwhelmed by other sources, but at the depths where ARCA sits, a set of near-simultaneous flashes indicate such a shower.

Although the consequences of cosmic rays are ARCA’s primary targets, it can also see the flashes produced when deep water muons produce a similar shower. Muons at these depths are produced by neutrinos striking molecules. The shower from a muon whose neutrinos came from above is almost impossible to distinguish from one produced by a cosmic ray.

Ordinary neutrinos, however, can pass through the Earth unscathed before producing a muon, so when we see a shower coming up, not down, it indicates a neutrino as the originator. Unfortunately, very high energy neutrinos, somewhat counterintuitively, are stopped by the bulk of the Earth that lets other neutrinos through.

Therefore, most of the ultra-high-energy neutrinos ARCA and similar detectors do pick up have directions that could equally be those of cosmic rays. Professor Elisa Resconi of the Technical University of Munich told Nature: “We have this narrow region in which we can see very clean signatures of these neutrinos.” The region covers neutrinos that come in nearly horizontal; one of the pieces of information Coelho was willing to reveal was that the neutrino in question was on an angle of about 1 degree above the horizon.

With ultra-high-energy neutrinos being so hard to detect, only by building a lot of detectors or waiting a very long time, will we find many more particles like this one. ARCA will do its bit – so far it has 28 detection strings, but that is planned to expand to 230. The conference heard four more observatories are already being built, or are under consideration.

The findings were presented at the Neutrino 2024 conference in Milan, Italy, on June 18.

Source Link: Most Powerful Neutrino Ever Seen May Have Been Identified By Unfinished Deep-Sea Detector