Paleontologists are very confident that dinosaurs didn’t wrap their dead after removing their organs like the ancient Egyptians or Incas – nor did they attempt self-mummification, like certain monks from one Buddhist tradition. Despite this, we have found some dinosaur fossils described as “mummified” because at least some of the skin has survived.

Skin preservation is rare in fossils, and paleontologists have thought of it as requiring a remarkable combination of circumstances. However, recent discoveries suggest it’s not quite as rare as previously thought. Dr Stephanie Drumheller of the University of Tennessee–Knoxville and colleagues have presented an explanation for why there may be more dinosaur fossils with skin in the game than expected.

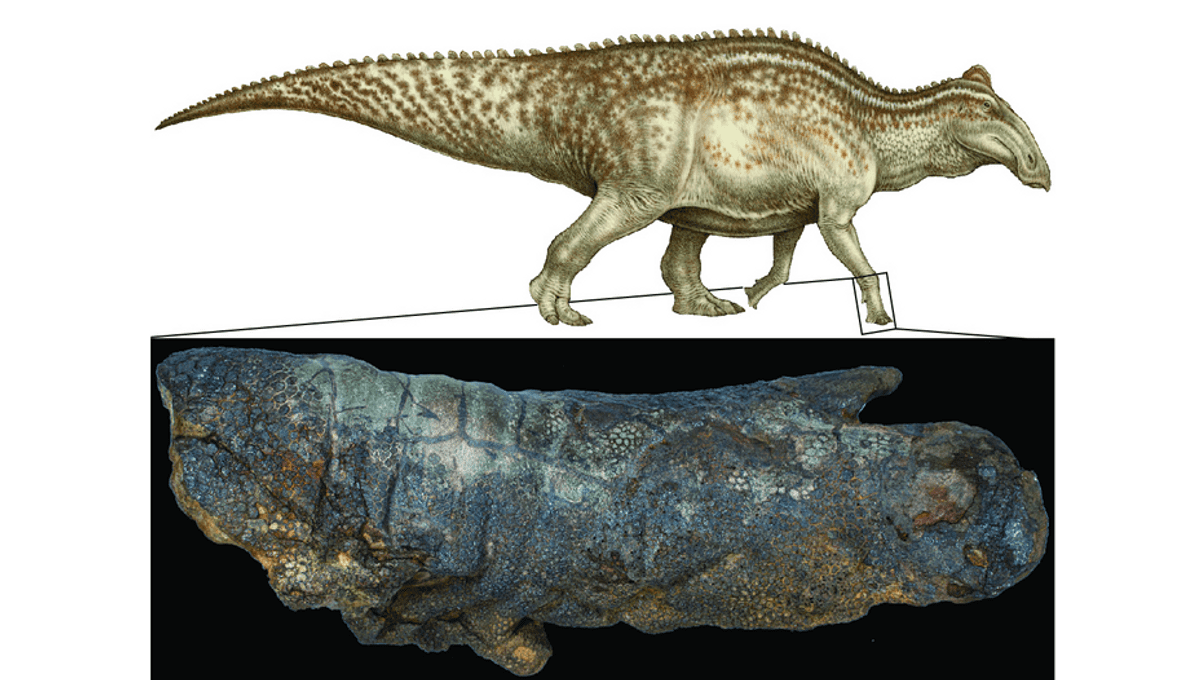

The traditional view of mummification holds that skin preservation requires the carcass to become desiccated and then buried so quickly that neither scavengers nor decomposing bacteria could get at it. So, the discovery of an Edmontosaurus called NDGS 2000 near Pretty Butte in the Hell Creek formation with bite marks on patches of surviving skin posed a problem. These are the first reported signs of carnivory on a mummified dinosaur.

Clearly, this specimen had not been protected by quick burial from scavengers – yet mummification had occurred nonetheless, even including degraded proteins to show the skin is original, not an infilled cast.

Drumheller’s explanation is that Edmontosaurus skin was not considered a delicacy in the late Cretaceous. Instead, the crocodile relatives feasting on this unfortunate individual wanted to get at its internal organs. The bite marks on the skin represented their efforts to remove an obstacle. Once the barrier was dealt with, they ate the tasty bits and left the skin and bones. The holes the carnivore made allowed “Gases, fluids and microbes associated with decomposition to escape,” the paper proposes.

The authors have given the process the catchy name “desiccation and deflation, and note it has been observed to preserve modern mammal skins. They are not suggesting all previous dinosaur mummies – including the astonishingly preserved hadrosaur currently being extracted – were made this way. Instead, they propose there are at least two paths by which dinosaur skin was transformed into something that could survive the ages.

Even were it not for NDGS 2000, the authors note there’s a problem with the conventional explanation of mummification since desiccation and rapid burial don’t really go together.

“Explanations for these conflicting preservational pressures are often speculative and unsatisfactory, as they rely on unrealistically rapid modes of desiccation or disregard the effects of smaller scavengers and decomposers,” the paper argues.

The problems are even greater for dinosaurs that died in wet environments, as was probably the case for this Edmontosaurus, given the climate in North Dakota at the time and the crocodyliform tooth marks on its bones.

Often only small patches of dinosaur skin survive, but that is not the case for NDGS 2000 – most of its back half’s skin has survived, along with its front right leg.

Co-author Dr Clint Boyd of the North Dakota Geological Survey noted in a statement; “Soft tissues like skin can … also provide a unique source of information about the other animals that interacted with a carcass after death.”

The paper is published open access at PLOS ONE.

Source Link: Mummified Dinosaurs Are Surprisingly Common, And Now We Know Why