Venus flytraps (Dionaea muscipula) can not only count, they do it better than a great many animals that can’t get past three or four. The evolutionary benefit is well understood, but how a plant achieves this feat is a mystery. Just as mice with a deactivated gene can teach us what that does for other members of their species, the discovery of a mutant D. muscipula lacking mathematical capacities could reveal where other flytraps get their skills.

In 2016, Professor Rainer Hedrich of Universität Würzburg revealed Venus flytraps can count to five but has followed up this week with an important exception explained in a new paper.

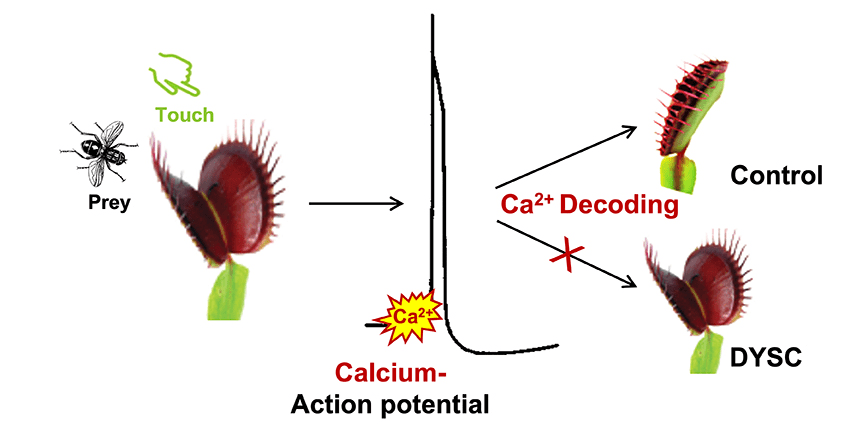

Venus flytraps have tiny hairs on the inside of their jaws, which when triggered provide electrical stimulation that induces calcium waves. The plant needs to be able to distinguish between potential prey and other triggers like a raindrop or a strong gust of wind, so it only closes after two rounds of stimulation in quick succession.

Hedrich’s previous work revealed that even after the trap has sprung shut the plant can’t afford to waste the jasmonic acid it uses to turn prey to goo on false alarms. Consequently, the hairs must be triggered three more times by a trapped insect’s struggles before the acid is released.

Dr Sönke Scherzer was a co-author on the previous research and subsequently attended a plant fair where a horticulturalist was displaying a flytrap whose jaws don’t close, let alone produce the jasmonic acid needed to turn prey into nutritious goo. Further investigation showed the traps are capable of closing, but the plant does not register the triggering mechanism.

“This mutant has obviously forgotten how to count, which is why I named it Dyscalculia,” Hedich said in a statement. Besides the plant, dyscalculia is the numerical equivalent of dyslexia, causing intelligent people to struggle with mathematics.

When stimulated by prey (or a meddling scientist) normal flytraps snap shut on the second touch, but Dyscalculia does not. Image Credit: Dr Ines Kreuzer/University of Wurtzburg

Hedrich confirmed Dyscalculia has the same capacity for touch perception as other Venus flytraps and could process insects the scientists treated with jasmonic acid and fed to it. The problem lies in between, with the plant lacking the capacity to count the number of calcium signals induced by insect touch to know when to snap the trap shut.

The team is focusing in on the parts of the flytrap genome related to calcium signaling in order to find what is different about Dyscalculia’s genes from other D. muscipula. They hope this will lead them to the genes responsible for the counting mechanism, and therefore how it is done.

A predatory animal that couldn’t work out when to shut its jaws on its prey would probably not live long enough for us to study it. However, flytraps get the bulk of their nutrients from the soil, air, and sunlight like other plants. Insects are just a supplementary meal to make up for the poor nutrient availability in their native Carolina wetlands, so when grown on a suitable substrate Dyscaculia thrives.

The study is published in Current Biology.

Source Link: Mutant Venus Flytraps Have Lost Their Ability To Count