The complexity of our languages is one of the things that distinguishes humans from other animals – but for most of that time, people may not have thought too hard about the structure of speech that evolved organically. Sometime between the 6th and 4th century BCE, the Indian scholar Dakṣiputra Pāṇini wrote down some rules describing the workings of Sanskrit. Over 2,000 years later, his work was read by Europeans and helped establish the science of linguistics for all human languages.

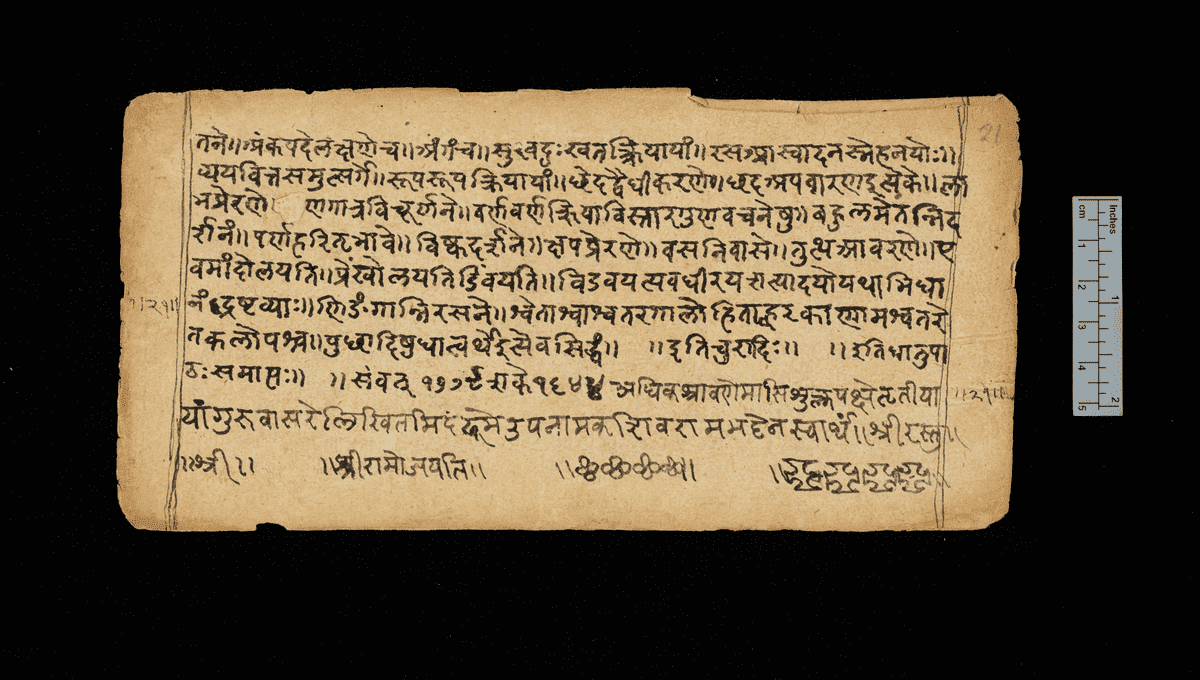

Pāṇini wrote almost 4,000 verses describing rules of what are now fields of knowledge such as syntax and semantics. His work is particularly noted for the study of how words are formed and relate to others from the same language, now known as morphology.

He described a “language machine”, an algorithm that has been compared to Alan Turing’s early computers, to construct grammatically correct Sanskrit words. Much of Pāṇini’s technique is applicable to other human languages, but those who came after him struggled to follow some of these rules even in the original.

Now, University of Cambridge PhD student Rishi Rajpopat claims to have decoded the language machine in his thesis, published today by his university. Rajpopat says his work allows the correct application of the machine, possibly for the first time since Pāṇini died – and it could have implications for teaching computers to understand human speech.

The problem subsequent scholars have found with Pāṇini’s work is that sometimes more than one of his rules could be applied at a particular stage of word building, with no obvious way to determine which to use. It would be like putting together a piece of Ikea furniture only to find that two pieces both fit, and the instructions didn’t tell you which will result in the outcome you seek…as if that would ever happen.

Rajpopat argues the fault lies not with Pāṇini, but with those who have sought to follow his instructions. Pāṇini provided a metarule to determine which rule was applicable where multiple options apply, but Rajpopat claims this has been misinterpreted, possibly since the beginning.

Part of what made Pāṇini so effective was the way he provided an order for grammar. Scholars have interpreted his metarule as instructing; “In the event of a conflict between two rules of equal strength, the rule that comes later in the grammar’s serial order wins.”

Rajpopat says the instruction was meant to reflect not the serial order, but the left and right side of the word, with rules that applied to the right side of the word given precedence, that is, later in the word not the order. When he applied this metarule, Rajpopat claims it almost always produced grammatically correct results.

Creating grammatical tools for a language that has not had any native speakers for thousands of years may not seem like something that will affect many people’s lives. However, Sanskrit remains influential both as the sacred language of Hinduism and a parent tongue to some of the most widely spoken languages today.

Moreover, with Pāṇini’s work having inspired the linguists’ approach to other languages, the successful application of his machine could inspire a search for equivalent algorithms in other languages. It could also prove important in how humans and machines communicate. “Computer scientists working on Natural language Processing gave up on rule-based approaches over 50 years ago,” Rajpopat said in a statement. That may now change.

Source Link: Mystery Of Instructions Left By The “Father Of Linguistics” Finally Decoded After 2,500 Years