A gold-plated pendant thought to date back to the late 12th century has been analyzed using a neutron-based imaging technique, revealing its innermost secrets for the first time. The painstaking work was conducted by a team from the Leibniz-Zentrum für Archäologie at the Technical University of Munich.

The ornately decorated pendant was first unearthed in 2008 in the German city of Mainz, in the remnants of a medieval rubbish dump. It was immediately obvious that the pendant had been designed to open like a locket – but, frustratingly, centuries worth of damage meant that revealing its contents would be no easy feat.

“Centuries of corrosion have heavily damaged the object as a whole and especially the lock mechanism; opening the pendant would have meant destroying it beyond all hope of repair,” said restorer Matthias Heinzel in a statement.

Not to be deterred, the team turned to two different techniques involving neutrons.

The first of these was neutron tomography. Similar to computed tomography (CT) scans that are used in medicine, this is an imaging technique that allows the internal structure of objects to be visualized. When conventional X-rays were not enough to know for sure what was inside the pendant, the restorers used this more advanced method.

The second technique is called prompt gamma-ray activation analysis (PGAA). A beam of neutrons is fired at the object being studied. Some of the neutrons are absorbed by the nuclei of the different chemical elements the object contains, in a process called neutron capture. Almost immediately (hence “prompt”), these new compound nuclei release a burst of gamma rays, which returns the elements to their previous state. The PGAA apparatus measures these gamma rays using a detector made of germanium, so researchers can determine the presence and amounts of different elements in the object.

The key thing with both of these techniques is that they are non-destructive, so the team could analyze the pendant in great detail without the risk of damage.

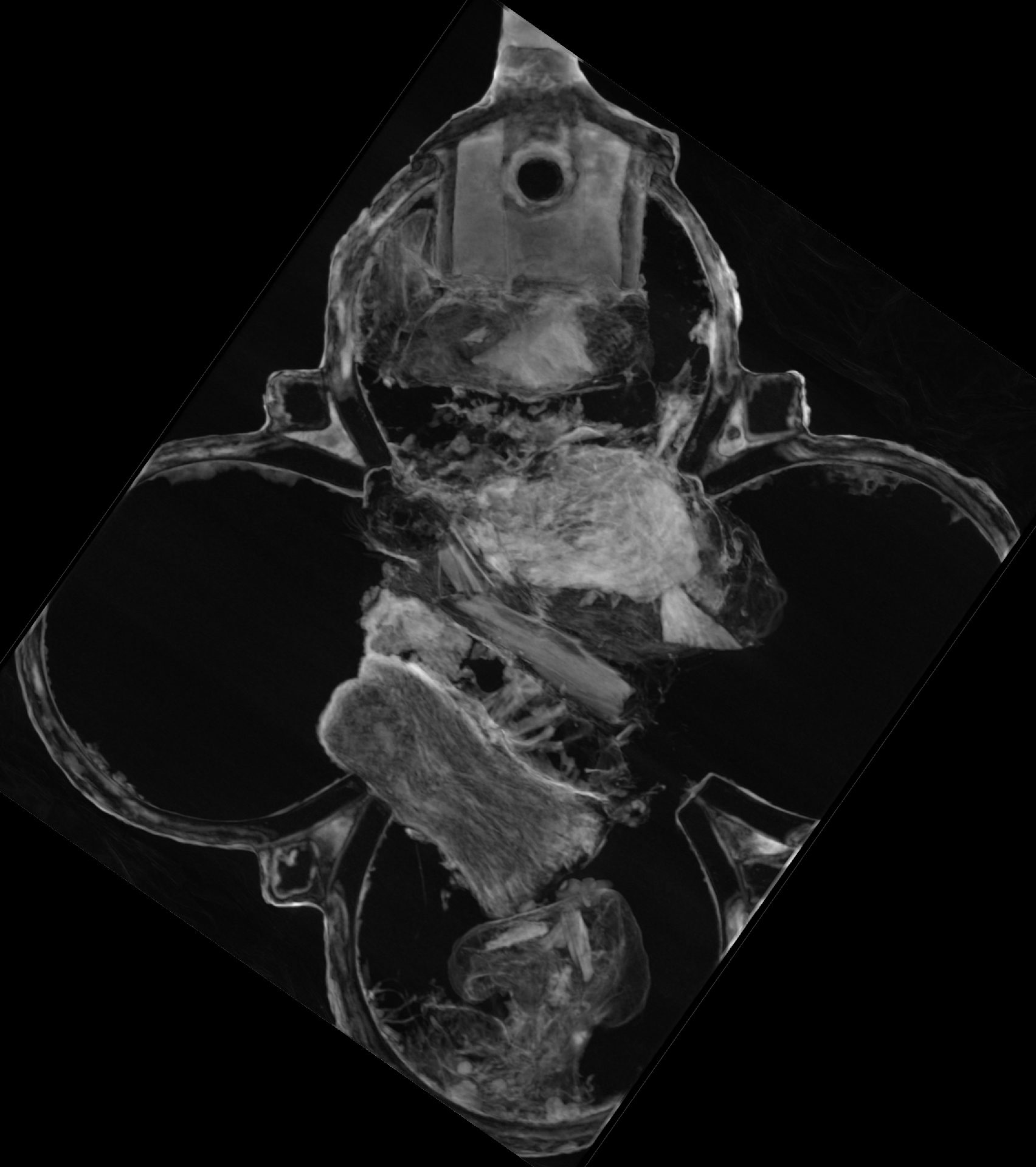

Heinzel first had to spend a staggering 500 hours cleaning up the artifact, which measures only 6 centimeters (2.4 inches) in height and width, and 1 centimeter (0.4 inches) in thickness. Neutron tomography and PGAA then revealed that there were tiny packages inside the pendant, containing fragments of bone.

The neutron tomography images revealed five packages inside the pendant. Image credit: Burkhard Schillinger, MLZ

Add to this the decorative images of Jesus and other Christian figures that adorn its outer surfaces, and the team suspects that the pendant may have been a reliquary – an object designed to carry materials of religious value.

“We can’t say whether or not these bone splinters are from a saint and, if so, which one,” explained Heinzel. “Usually relic packages contain a strip of parchment indicating the name of the saint. In this case, however, we unfortunately can’t see one.”

Archaeologists are only aware of three other such reliquaries from this time period. They are more properly known as phylacteries, and were designed to be worn on the body. In this case, the analysis revealed a fragment of silk, suggesting that the pendant could have been worn on a silk cord around the neck.

The 800-year-old pendant is currently on display at the Mainz State Museum – and, thanks to this interdisciplinary team and their non-destructive neutrons, it has been preserved for future generations to admire for many years to come.

The research was presented at The 10th Interim Meeting Of The ICOM-CC Metals Working Group, and subsequently published as a paper in the conference proceedings.

Source Link: Mystery Of Medieval Pendant Full Of Bones Solved Using Neutrons