Neighboring Neanderthal communities living in the Middle East some 60,000 years ago appear to have developed distinct butchering practices, suggesting that different families may have had their own culinary traditions. By examining cut marks on animal bones found at two nearby Neanderthal sites in Israel, researchers found that foodie culture varied from cave to cave, all of which adds to our understanding of the behavioral complexity of our extinct sister lineage.

“For a long time we had this idea of Neanderthals as being very focused on survival and not very culturally developed,” said study author Anaëlle Jallon. Only in recent years has this view started to change, with increasing evidence for localized Neanderthal culture.

If they were so focused on survival, we would expect to see that they just always used the most efficient way of butchering the same animals. But this turns out not to be the case.

Anaëlle Jallon

“For example, in the Levant you can see they had different ways of producing tools in different sites,” Jallon told IFLScience. “And now we can see it in a behavioral aspect that is as important for survival as butchering meat and eating.”

“If they were so focused on survival, we would expect to see that they just always used the most efficient way of butchering the same animals. But this turns out not to be the case,” she explained.

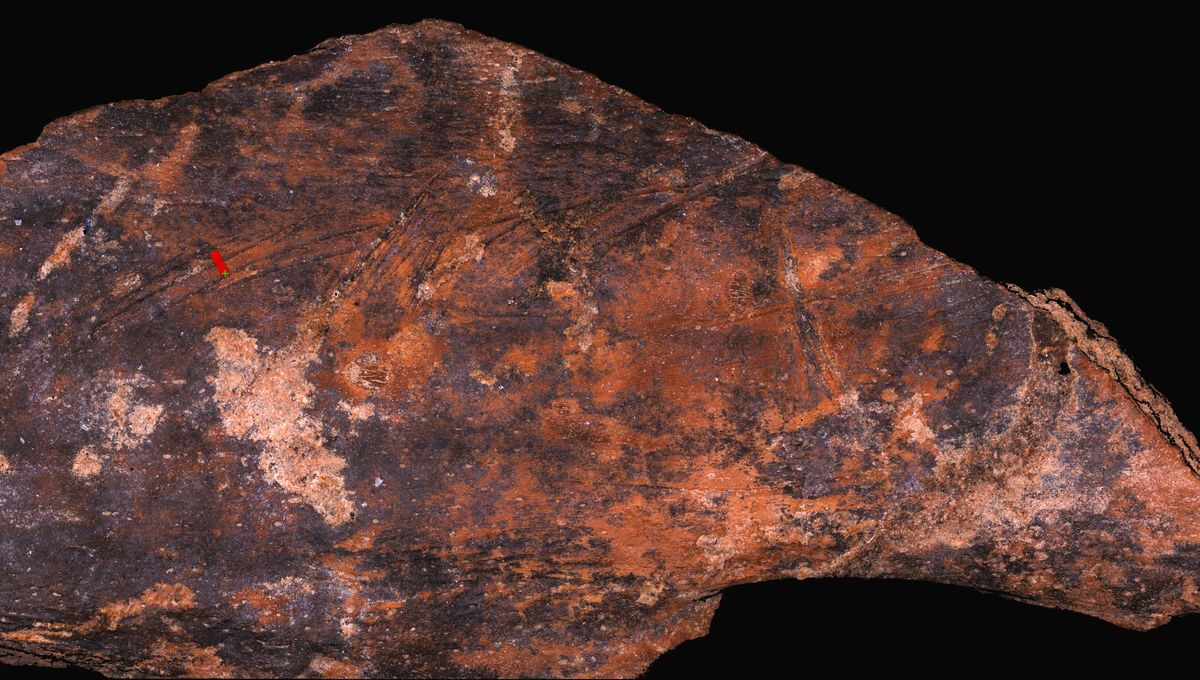

To learn about Neanderthal butchering habits, the study authors conducted microscopic and macroscopic analyses of cut marks on 344 animal bones found in the Amud and Kebara caves, which are about 70 kilometers (43 miles) apart from one another. Both were occupied by Neanderthals between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago, and the communities in the two caves would have consumed the same prey and used the same tools.

Surprisingly, however, the study authors write that “the broadly contemporaneous groups of Neanderthals that occupied Amud and Kebara caves exploited similar communities of ungulates in nuancedly different ways.”

For instance, Jallon says that when the team looked at the long bones of smaller mammals like gazelles, they found that the assemblage at Kebara typically consisted of large fragments featuring “little clusters of not so many cut marks, and a lot of isolated cut marks.” In Amud, meanwhile, she explained that “what we have are very small fragments covered in cut marks that are all overlapping each other in all directions.”

Based on practical experiments, the researchers conclude that these differences can’t be explained by varying levels of butchery skill, nor are they caused by different tools or other resources. Instead, the contrasting cut mark patterns appear to be the result of cultural preferences in the two caves.

“We don’t have a lot of other sources of data to explain what these differences were exactly, but it could be in the way that they organized the group,” says Jallon. “Maybe in Amud, everybody cut themselves a little piece of meat, creating a lot of different cut marks everywhere, while in Kebara there was one person designated to cut everything properly,” she speculates.

“That could be one explanation, but they could also have had different ways of preparing the meat. If they dried it or let it decay in Amud then it would be more difficult to cut, so it would leave different patterns of cut marks.”

Regardless of the specific butchery practices employed at each site, it’s important to note that these behaviors remained constant over numerous occupation phases, spanning thousands of years. This suggests that certain food processing techniques were taught and passed down from generation to generation, hinting at cultural transmission within Neanderthal communities over long periods of time.

The study is published in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology.

Source Link: Neanderthal Butchers From Different Caves Had Their Own Specialities