Infrared goggles are out, replaced by contact lenses that turn wavelengths too long for our eyes into those we can see, while letting through ordinary light at the same time. Remarkably, there’s no need for a power source, and slightly creepily, they’ve even been made for mice.

Night-vision goggles rely on the fact that living things, and many machines, produce heat at wavelengths far too long for the human eye to see. By capturing these wavelengths and emitting photons within the human range of vision, the goggles allow us to see in the dark, at least making out many important targets.

New contact lenses do the same thing, but by operating on a vastly smaller scale, they avoid the need to carry around heavy equipment. Moreover, because they’re highly transparent at optical wavelengths, wearers can see things they can normally, and the modified infrared signals at the same time. That combination could potentially become quite confusing, but no one said having superpowers was easy.

Many materials can absorb electromagnetic radiation in one part of the spectrum and release it at longer wavelengths. That’s why so many mammals’ fur, among many other things, glows under black lights; the ultraviolet is converted to the narrow window of light we can see.

Shifts in the other direction, known as upconversions, are a great deal harder, since each photon released has more energy than those absorbed. However, Professor Tian Xue of the University of Science and Technology of China has taken advantage of nanoparticles that do just that, by combining the energy of two or more into one. These particles can collect 800-1,600 nanometer photons and re-release light in the 400-700 nm range our eyes have evolved to capture.

By embedding the nanoparticles in flexible polymers, Xue and co-authors created miniature contact lenses for mice. Although the mice couldn’t tell the authors what they were seeing, their behavior revealed their new powers of vision. Given a choice between a dark box and one lit up in infrared, the contact-wearing mice chose the dark option, whereas their normal-sighted counterparts couldn’t see a difference. Removable contacts seem preferable to injecting the particles into their eyeballs, as has been done previously.

The contacts were then expanded to human size, and the team tested the effect first under conditions without visible light.

“It’s totally clear cut: without the contact lenses, the subject cannot see anything, but when they put them on, they can clearly see the flickering of the infrared light,” Xue said in a statement. “We also found that when the subject closes their eyes, they’re even better able to receive this flickering information, because near-infrared light penetrates the eyelid more effectively than visible light, so there is less interference from visible light.” Sounds great, if you’re not trying to sleep.

Contact lenses might give this technology the maximum sci-fi feel, but they don’t produce high-resolution images, as the light particles scatter so close to the retina. Indeed, at the moment, wearers can’t make out an infrared source like body heat.

The demonstrations were only successful using infrared LEDs, which not only emit a lot of photons, but produce them at a specific wavelength, rather than a spectrum. The use of these narrow wavebands probably made it much easier for people trying to interpret the dual inputs of ordinary light and upconverted infrared at the same time.

Glasses made out of the same material can produce sharp images of infrared sources, however. (If this has been done with mice, we have been deprived of the photos of them wearing infrared glasses). As with any prototype, the creators see scope for improvement.

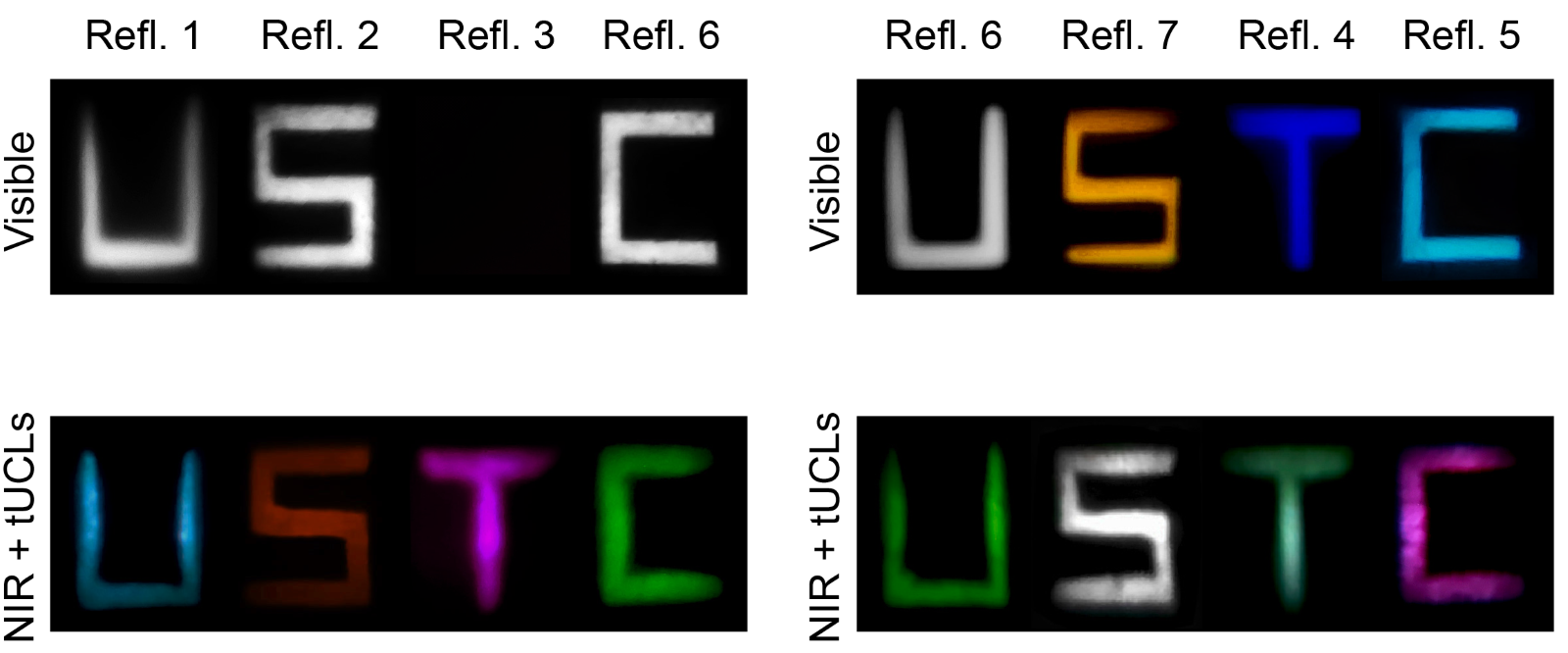

The simplest version of the lenses only produced monochrome images, with all infrared light out to 1,600 nm looking the same. However, the team found they could do better. By tweaking the nanoparticles and embedding the lenses with multiple versions, they translated 980 nm photons to blue light, 808 nm to green, and 1,532 nm to red.

In real-world situations, that could make for a somewhat distorted experience, because green is triggered by the shortest infrared radiation, rather than the one in the middle. The paper does not explain this counter-intuitive choice, but reports that participants wearing the lenses successfully adjusted lights combining red, green, and blue until they matched the ratios they were seeing from the upconverted infrared. They could also recognize patterns formed from differently colored infrared sources.

Patterns that appear faint, and in most cases monochrome, are revealed in different colors when specific infrared wavelengths are converted to particular colors.

Image Credit: Yuqian Ma, Yunuo Chen

“In the future, by working together with materials scientists and optical experts, we hope to make a contact lens with more precise spatial resolution and higher sensitivity,” Xue said.

Besides a large market from novelty seekers, and potential applications on night patrol, Xue sees potential for helping color-blind people. Instead of converting infrared to visible light, one shade of visible light could be converted to another, helping people recognize colors they currently can’t.

The study is published in Cell.

Source Link: New Contact Lenses Give You Infrared Vision Even With Your Eyes Shut