Using satellite images and aerial photography, archaeologists have uncovered a network of previously unknown and huge Bronze Age sites at the heart of Europe. The team believe these newly identified structures could explain how contemporary megaforts, the largest prehistoric constructions made before the Iron Age, came into being.

The research was led by archaeologists from University College Dublin and colleagues in Serbia and Slovenia, who “stitched together” the images and photos to give an impression of the prehistoric landscape of the southern Carpathian Basin. Through this work, they were able to find over 100 sites that belonged to a complex ancient society.

It is likely that their use of defensible enclosures served as precursors to the large hillforts that have become iconic examples of Bronze Age construction.

“Some of the largest sites, we call these mega-forts, have been known for a few years now, such as Gradište Iđoš, Csanádpalota, Sântana or the mind-blowing Corneşti Iarcuri enclosed by 33 km [21 miles] of ditches and eclipsing in size the contemporary citadels and fortifications of the Hittites, Mycenaeans or Egyptians,” lead author Associate Professor Barry Molloy, UCD School of Archaeology, said in a statement.

“What is new, however, is finding that these massive sites did not stand alone, they were part of a dense network of closely related and codependent communities. At their peak, the people living within this lower Pannonian network of sites must have numbered into the tens of thousands.”

All the sites discovered by this work were located in the hinterlands of the Tisza river, a major river in Central and Eastern Europe, which now extends through several national boundaries. As such, the previously unknown communities of people who lived at these sites are being collectively referred to as the Tisza Site Group (TSG).

The Tisza Site Group (TSG) are thought to have been a sophisticated community that lived and cooperated along the banks of the Tisza river.

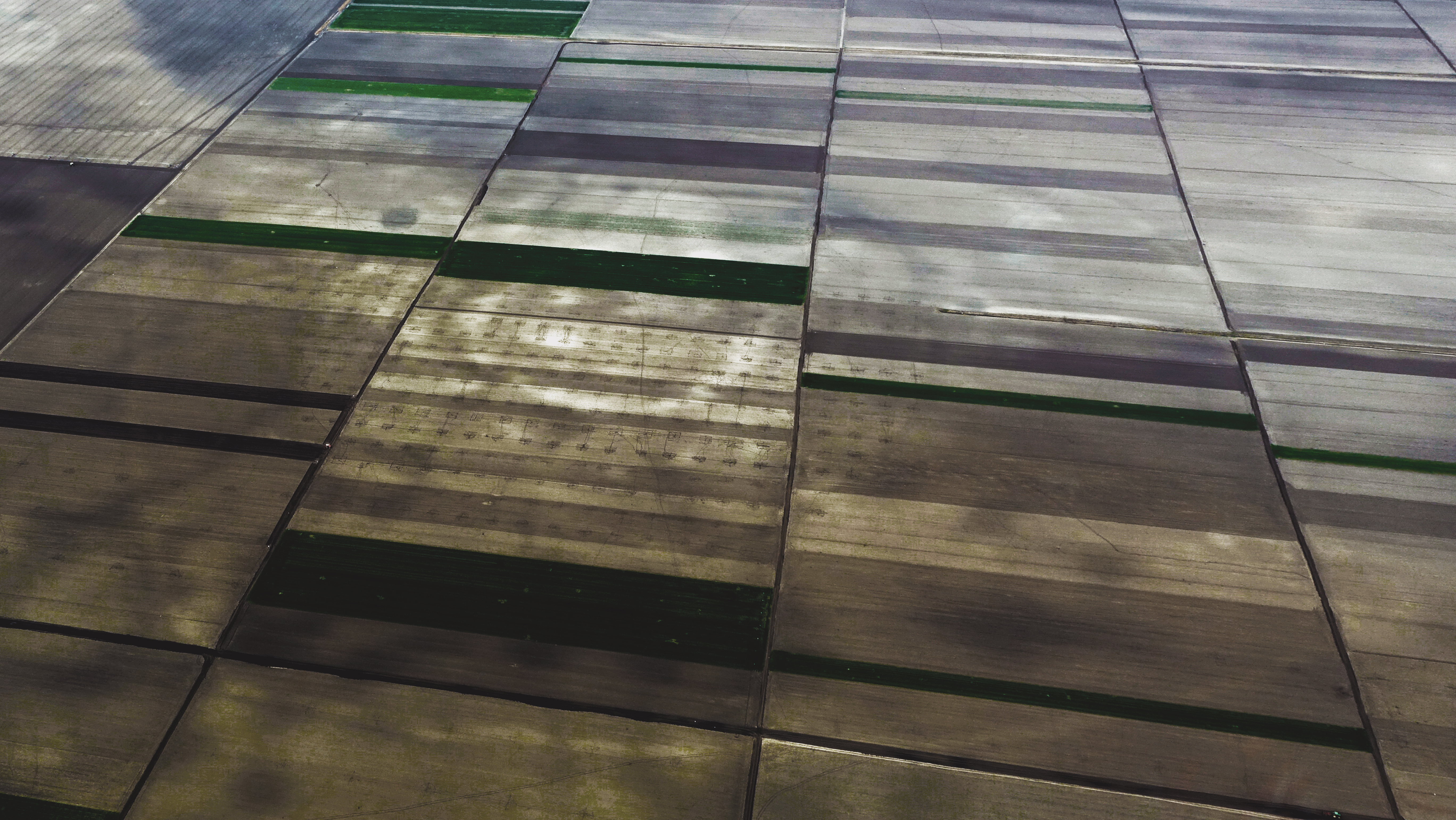

Image courtesy of Professor Barry Molloy, University College Dublin

Almost all of the TSG sites are within 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) of one another and lie along a river corridor created by the Tisza river and the Danube. This has led the archaeologists to believe that the communities were likely cooperative, allowing them to spread out like this.

Interestingly, the research indicates that the TSG were important centers of innovation in prehistoric Europe and functioned as a major hub for the region at a time when the Mycenaeans, Hittites, and New Kingdom Egyptians were at their height – around 1500 to 1200 BCE.

This is commonly regarded as a major turning point in prehistoric Europe’s story. During the second millennium BCE, so it appears, the advanced military and earthwork technologies of the society spread across Europe once they collapsed around 1200 BCE. The importance of this group of people now helps explain why material culture and iconography from across Europe was so similar at this time.

“Our understanding of how their society worked challenges many aspects of European prehistory. It would be extremely unlikely for each of these 100+ sites to have been individual chiefdoms competing with each other,” Molloy added.

“Uniquely for prehistoric Europe, we are able to do more than identify the location of a few sites using satellite imagery but have been able to define an entire settled landscape, complete with maps of the size and layout of sites, even down to the locations of people’s homes within them. This really gives an unprecedented view of how these Bronze Age people lived with each other and their many neighbours.”

“However, this was no peaceful time of plenty. Major innovations in warfare and organised violence took place at this time. The scale of this society indicates it was relevant and powerful on a European stage and between force of arms and major defensible features at settlements, they were well equipped to defend their gains.”

How it’s done

Archaeology is more than just trowels and holes. To identify these new sites, the team used a barrage of cutting-edge imaging technologies to map out this ancient landscape.

Armed with the findings from the satellite images, the team could begin their excavations on the ground.

Image courtesy of Professor Barry Molloy, University College Dublin

“We tested the findings from satellite images on the ground using survey, excavation, and geophysical prospection,” Molloy explained. “The vast majority of sites were established between 1600 and 1450 [BCE] and virtually all of them came crashing down around 1200 [BCE], being abandoned en masse.”

“1200 [BCE] was a striking turning point in Old World prehistory, with kingdoms, empires, cities, and whole societies collapsing within a few decades throughout a vast area of southwest Asia, north Africa, and southern Europe.”

“It is fascinating to discover these new polities and to see how they were related to well-known influential societies yet sobering to see how they ultimately suffered a similar fate in wave of crises that struck this wider region.”

The paper is published in PLOS ONE.

Source Link: New Satellite Images Reveal Europe’s Hidden Bronze Age Megastructures