New research is opening a window into the brain’s prediction machinery, showing how two brain regions work together when something unexpected happens. As well as offering a deeper insight into how our brains constantly work to fill in the gaps and guess what’s coming next, the findings could really help people experiencing difficulties with perception and sensory processing.

“I was deeply fascinated by the fact that our brain functions as a prediction machine,” first author Dr Shohei Furutachi told IFLScience. “It uses prior knowledge – what neuroscientists call an ‘internal model’ stored in the brain – to anticipate sensations and the outcomes of our actions.”

But what about when those predictions turn out to be wrong?

“When there’s a discrepancy between what’s expected and what actually occurs, referred to as a prediction error, the brain uses this information to update the internal model and direct our attention to unexpected events,” Furutachi told us.

As important as this process undoubtedly is, very little was known about it, which inspired Furutachi and the team to embark on their research.

The team put mice into a virtual reality environment after they had trained them to run continuously while receiving a periodic reward of a lick of strawberry milk. As the mice ran along the “corridor”, the experimenters were able to manipulate the environment to introduce unexpected images on the walls.

While the mice jogged through their virtual world, a technique called two-photon calcium imaging was used to record activity from neurons in the primary visual cortex, the first stop for information from the eyes.

They discovered that when the mice encountered an unexpected stimulus, the brain selectively boosted the activity of neurons that were most attuned to that stimulus. It’s not a general “something is wrong” signal – more like the brain drawing attention to specifically what in the visual environment was outside of its predictions.

With optogenetics – using light to activate or silence groups of neurons – the team was able to narrow things down to two distinct groups of cells that are key to this prediction error signal.

Historically, this area of study has seen much debate and has even been humorously dubbed the ‘grave of ambitious PhD students’

Dr Shohei Furutachi

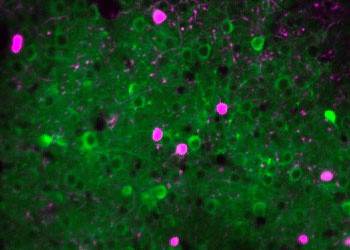

“The most striking finding from our study was the synergistic interaction between the neocortex and the higher-order thalamus,” Furutachi told IFLScience. “We discovered that when specific inhibitory interneurons in the neocortex, known as VIP neurons, are inactive, thalamocortical input suppresses cortical activity. However, when these neurons are active, thalamic input enhances cortical responses.”

“Essentially, VIP neurons act as a switchboard, activated by sensory prediction errors, to dictate how thalamic inputs interact with the neocortex.”

Mouse visual cortex neurons, with the VIP neurons highlighted in magenta.

Image credit: SWC Hofer Lab

The neocortex and thalamus are known to be closely connected and even evolved together, but precisely how they interact has been difficult to pin down. “Historically, this area of study has seen much debate and has even been humorously dubbed the ‘grave of ambitious PhD students’ due to its complexity and the controversial nature of its research findings,” Furutachi told us.

“Our discovery of this synergistic interaction may resolve some of these longstanding contradictions and provides a clearer understanding of how these critical brain regions interact.”

The study was limited to mice, but “since the neural circuits we studied in mice are conserved in humans, we anticipate that these findings could indeed translate to humans,” Furutachi said. “Future studies could corroborate our results using advanced techniques that allow neuroscientists to study sensory processing of humans at the level of individual cells, utilizing non-invasive or minimally invasive methods.”

This type of research could be very important for understanding conditions and disorders that affect perception, such as schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSD).

“SSDs may involve incorrect internal models of the world due to diminished prediction error signaling, leading to incorrect sensory perception even in the absence of sensory input – hallucinations,” Furutachi explained.

Conversely, in autistic individuals, differences in error signaling could explain the sensory hypersensitivity that many experience: “overly precise predictions or the inability to correctly update predictions could result in excessive prediction error signals and therefore hypersensitivity to sensory stimuli, making it hard to ignore irrelevant details.”

Furutachi and the team now plan to investigate two of the key components of these prediction error signals: how the brain makes its predictions in the first place, and how it computes the errors.

“By shedding light on these underlying mechanisms,” Furutachi told IFLScience, “we aim to provide a foundational understanding of how we effectively perceive the world.”

The study is published in the journal Nature.

Source Link: Newly Discovered Brain Mechanism Helps Us Handle Surprises