Pterosaurs are intrinsically terrifying creatures, but a new discovery is more strange than frightening. Although possession of at least 480 teeth should probably make for nightmare fuel, the fact these resemble hair combs and were probably used to catch small crustaceans reorientates the picture.

While the rest of us are pondering whether the flying reptile would have been a threat were we suddenly transported back to the late Jurassic, paleontologists are more focused on how well-preserved the discovery is.

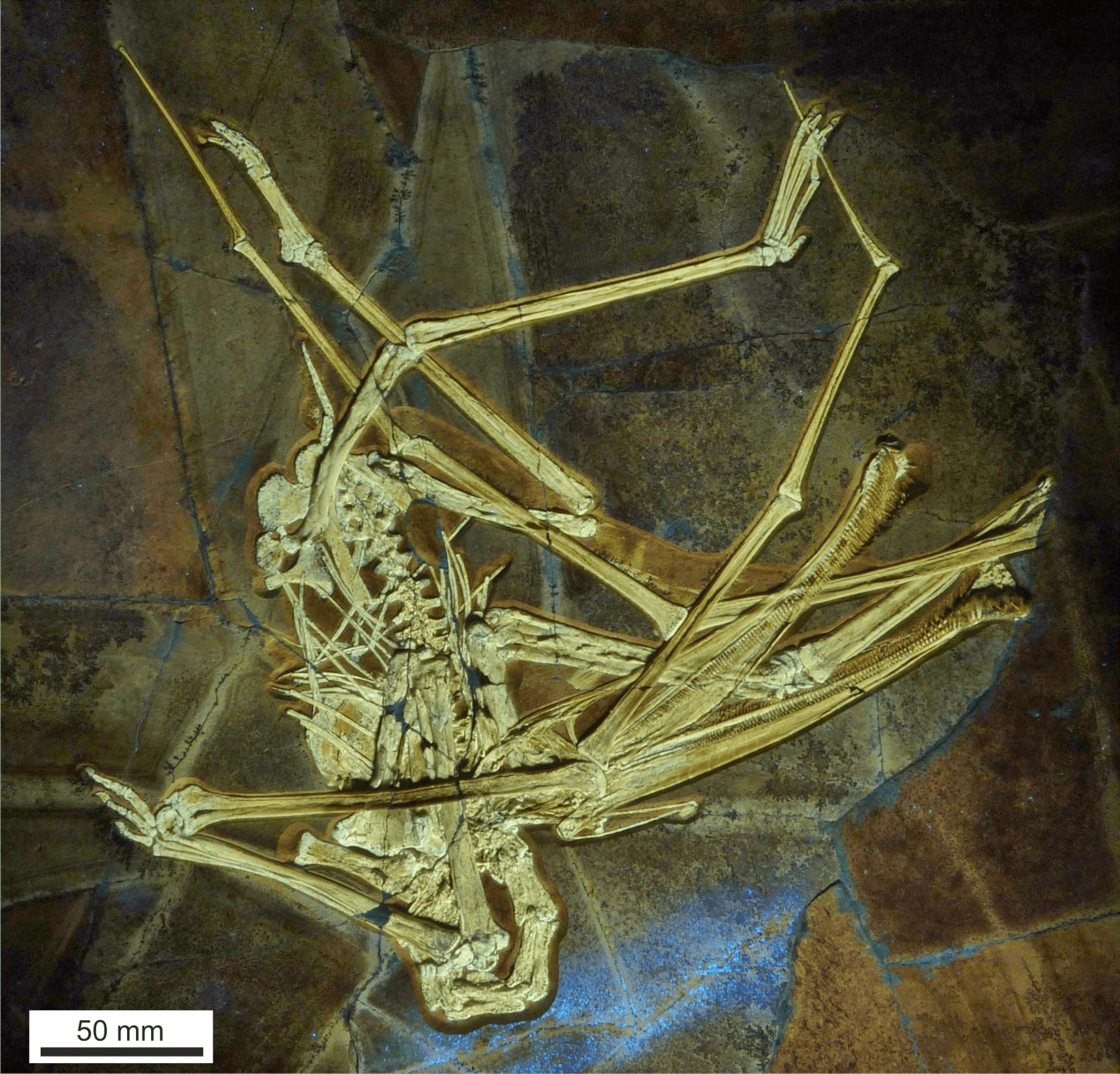

Pterosaur bones had to be light to allow them to fly, which meant they seldom fossilized well; in most cases, we have scrappy fractions of an animal. That’s not true for the creature that has been named Balaenognathus maeuseri in a new paper, where it has been identified as a member of the Ctenochasmatidae pterosaurs. The preservation is so good a small portion of the wing membrane survived.

“The nearly complete skeleton was found in a very finely layered limestone that preserves fossils beautifully,” said Professor David Martill of the University of Portsmouth in a statement.

“The jaws of this pterosaur are really long and lined with small fine, hooked teeth, with tiny spaces between them like a nit comb. The long jaw is curved upwards like an avocet and at the end it flares out like a spoonbill. There are no teeth at the end of its mouth, but there are teeth all the way along both jaws right to the back of its smile.”

Balaenognathus maeuseri got a little scrambled up over more than 100 million years, but most of it survived, most of the ribs aside. Image Credit: Martill et al/Paläontologische Zeitschrift

The preservation means we can see the diversity in the shape of the teeth, and Martill continued; “What’s even more remarkable is some of the teeth have a hook on the end, which we’ve never seen before in a pterosaur ever.”

Martill believes the Balaenognathus fed on small shrimp in shallow wetlands and the hooks were used to hold the crustaceans in the mouth prior to swallowing.

The team had no expectation of finding pterosaur bones when the discovery was made, instead opening a large limestone block that had crocodylomorph bones sticking out before it was quarried. Based on the preservation Martill believes; “It must have been buried in sediment almost as soon as it had died.”

The Bavarian limestone in which Balaenognathus was found has been a rich source of pterosaurs since 1784 when the order was first scientifically described.

Balaenognathus’s toothy grin was exceeded by Argentina’s Pterodaustro, but those were short on the top and long on the lower jaw, not symmetrical like Balaenognathus.

The long legs and shape of the beak are reminiscent of modern spoonbills, and Martill and co-authors think Balaenognathus filled a similar niche, wading or swimming through shallow lagoons and scooping up water to funnel out. Prey would have been trapped inside the mouth for consumption. Unlike spoonbills, Balaenognathus would have been unable to feed by pushing its bill through the water. Instead, it either relied on passive suspension feeding in fast-flowing creeks or tidal channels, or a pumping mechanism similar to some ducks.

Strange as Balaenognathus may look to our eyes, the authors place it as one of the closer members of the pterosaur family to the original Pterodactylus.

Balaenognathus means “whale mouth”, reflecting the similarity to the feeding strategy of baleen whales. The species name refers to beloved co-author Matthias Mäuser, who died before the paper was published. “Matthias was a friendly and warm-hearted colleague of a kind that can be scarcely found. In order to preserve his memory, we named the pterosaur in his honor,” Martill said.

The study is published open access in the journal Paläontologische Zeitschrift

Source Link: Newly Discovered Pterosaur Had More Than 400 Hooked Teeth