Archaeologists from the Université Bordeaux have constructed a continent-wide database of personal ornaments worn by Europeans 34,000-24,000 years ago, a period known as the Gravettian technocomplex. Combining the locations at which these were found with genetic data revealed nine distinct cultures. “We demonstrate that Gravettian ornament variability cannot be explained solely by isolation-by-distance,” the authors write.

Humans have been adorning our bodies with items such as shells for at least 140,000 years. Over time, the range of the items used grew, and around 45,000 years ago, there was an explosion in the diversity of types of beads made from bones, shells, ivory, and stones, among other raw materials.

At this point, the authors of the study note, jewelry became a useful cultural marker for modern archaeologists. “The idea behind this approach,” they write, “is that personal ornaments are a communication technology used to convey privileged information on group affiliation and social status.”

Items buried with someone may carry an extra significance – if nothing else, the fact that the culture engaged in burial, which was not universal at the time.

Some archaeologists have used differences in jewelry styles to distinguish cultures of the era. Others have disagreed, however, arguing that these reflect isolation by distance in an era when all travel was on foot. If seashells were not used far inland, for example, it might not represent a cultural discontinuity, but rather the difficulty of importing them.

It should be possible to test these two competing explanations, the authors of the latest study note. If the second interpretation is correct, the differences in styles will be determined by distance. On the first view, factors such as language, environment, and ethnic differences would also play a role. When looking back 30,000 years, we may not be able to measure some of these, but others will have left their mark.

To test which is correct requires a large database of ornaments and their locations, and that is what first author Jack Baker built for his PhD thesis, using examples from 112 sites.

Even by this time, shells were the most common ornaments, with 79 examples found, compared to 26 teeth and 29 made from other items. Although 13 of the shells could have originated inland, either being from freshwater species or made from fossils deposited in parts of Europe that were once underwater, the majority must have been brought from the coast, often far away.

Along with the raw materials, the study identified differences in the ornaments’ styles between locations. As Baker told Science Magazine: Gravettian culture was not “one monolithic thing”.

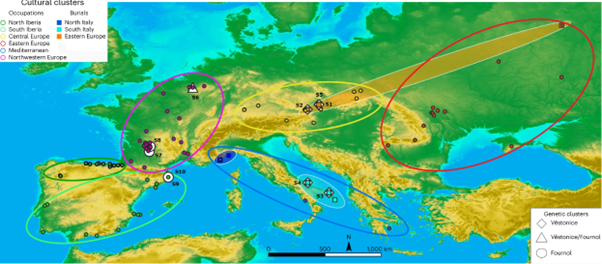

Although geographical distance was certainly a factor in the variation found between sites, the authors concluded it was far from the only one. They identified nine clusters of sites marked by commonalities in what was found at each. Three of these were composed of burial sites and six of places of occupation.

The location of the Gravettian cultural clusters on a map of modern Europe (sea levels at the time were 100 meters lower). Note the intriguing similarity between Europe and Greece, despite the sea between.

Image credit: Baker et al., Nature Human Behavior 2024

It’s not just the adornments that reveal cultural differences. In Eastern Europe, all the burial sites are from the Early and Middle Gravettian periods, with the practice apparently stopping for some reason thereafter. On the other hand, it was only in the Middle and Late Gravettian that burials appear to have occurred in Italy. Perhaps once they learned the Italians were doing it, Eastern Europeans cooled on the whole burial idea.

“Our results are consistent with the view that when choosing their personal ornaments, Gravettian hunter-gatherers followed, at least to some extent, conventions dictated by their sense of belonging to a cultural group, and that slightly permeable cultural boundaries existed between groups,” the authors write.

The recent ability to extract DNA from Ice Age humans has led to populations being identified by their genetic group rather than cultural items, as in the past. Baker and colleagues note evidence of a genetic discontinuity between western Europe at the time and central and southern parts of the continent, but clearly this was not the only cause of cultural divisions.

Professor Peter Jordan of Lund University, who was not involved in the research, told Science Magazine that in this study, “The archaeology strikes back, showing that we can generate new narratives that also use a very rigorous, quantitative approach to the study of material traditions.”

Much as genetic analysis has proven popular as the shiny new thing, Baker and co-authors note we have DNA from only a small number of individuals in the era, with much of the continent not covered.

The study is published in Nature Human Behavior.

Source Link: Nine Distinct Cultures Of Ice Age Europe Revealed By The Style Of Their Jewelry