The Northern Hemisphere’s summer was a scorcher, pushed off the charts by a combination of global heating and El Niño. Given the much higher baseline today, and how exceptional it was, some people speculated last summer may have been the hottest for 100,000 years, if not longer. That’s not a claim that can currently be tested, but new evidence shows summer 2023 was the hottest at least since the time of Jesus, and the 1.5°C (2.7°F) target agreed on in Paris nine years ago may be well behind us.

The further back we look in time, the hazier our estimates of global temperatures become. We have less than 50 years of satellite data covering the entire globe. There’s a bit over a century of records from widespread weather stations, and if we extrapolate from limited parts of the planet, we can go back to about 1850.

That doesn’t mean, however, that we have no capacity to compare modern temperatures with those of the past. Climate proxies such as the growth rings in trees, isotopes from air bubbles in ice, and limestone cave structures all tell us something useful. Professor Ulf Büntgen of the University of Cambridge is part of a team that used the summer proxies to put last year in context.

“When you look at the long sweep of history, you can see just how dramatic recent global warming is,” Büntgen said in a statement. “2023 was an exceptionally hot year, and this trend will continue unless we reduce greenhouse gas emissions dramatically.”

Büntgen and colleagues relied on tree rings to reach this conclusion. Growing conditions are reflected in the width of tree rings laid down in a specific year. In temperate and sub-polar zones where water is usually not a limiting factor, this generally reflects the warmth of the spring and summer. Individual trees’ growth may be affected by specific local factors, but with a large enough sample, it’s possible to gain an estimate of temperatures that tracks closely with measurements since they have been available.

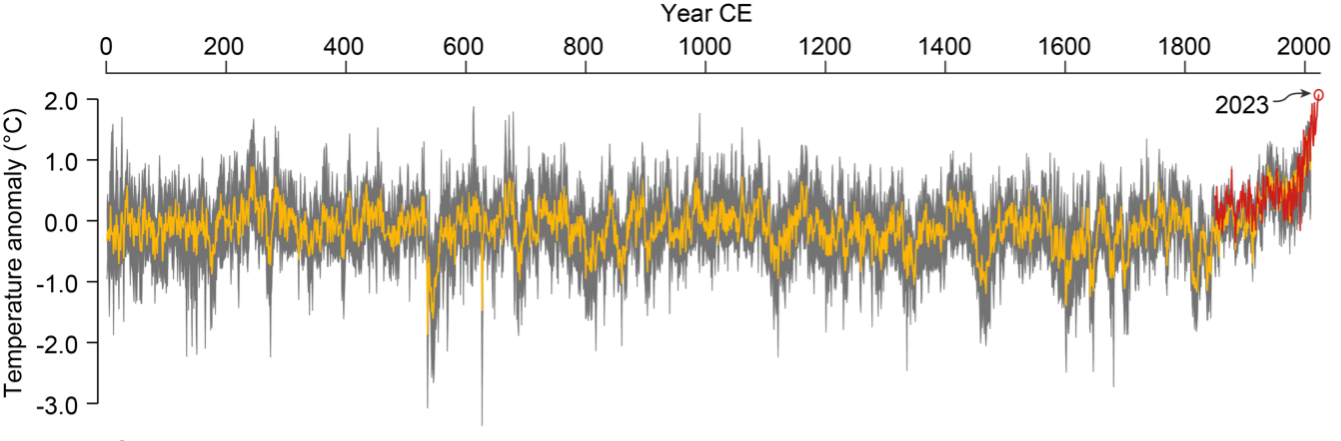

Instrumental summer land temperatures (red) shown together with the tree ring reconstruction mean (yellow) and 95% uncertainty range derived from the variance among tree ring members (grey).

Image credit: Esper et al 2024

Data is sparse for the Southern Hemisphere, and in the tropics factors besides temperature can be the dominant drivers of tree growth. To increase the accuracy of their estimates, Büntgen and co-authors restricted their analysis to areas between 30° North and the pole.

The work didn’t just prove 2023 was exceptional, it allowed the researchers to compare it with average conditions over 2,000 years, as well as with the coldest summer during that time. That was the year 536, when a “volcanic winter” worse even than the “year without a summer” hit. The growing season in Büntgen’s study area averaged 3.93°C (7.07°F) colder in 536 than last year.

Frequency distributions of the observed and reconstructed temperatures anomalies (0°C = 1850-1900 CE mean) with exceptionally cold and warm summers highlighted.

Image credit: Esper et al 2024

Prior to the point where human activity moved the climate into new territory, the hottest northern summer of the period was in 246, but even this was more than a degree (1.19°C or 2.14°F to be precise) cooler than 2023. The authors provide uncertainty ranges for the extreme years, but even the highest error bar doesn’t reach last year.

The research was informative for more than just extreme years. Comparing the tree ring data with the instrumental records available for a few locations from 1850 to 1900, the authors concluded we have over-estimated summer temperatures in the late 19th century by a few tenths of a degree. Recalibration makes 2023’s northern summer 2.07°C (3.73°F) above the 1850-1900 average.

This allowed a re-estimate of temperatures further back, placing last summer 2.2°C (3.96°F) above the pre-1850 average. “Such offsets fundamentally question the calculation of temperature ranges considered in the 2015 Paris Agreement using observational data,” the authors write.

“It’s true that the climate is always changing, but the warming in 2023, caused by greenhouse gases, is additionally amplified by El Niño conditions, so we end up with longer and more severe heat waves and extended periods of drought,” said Professor Jan Esper of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. “When you look at the big picture, it shows just how urgent it is that we reduce greenhouse gas emissions immediately.”

The study is published in Nature.

Source Link: Not Only The Hottest On Record, Summer 2023 Was Hottest For 2,000 Years