Octopolis and Octlantis are the ingenious nicknames given to two sites off the coast of Australia where surprising discoveries were made. Here, researchers stumbled upon two sites where the gloomy octopus (Octopus tetricus) was found living in burrows with neighbors. It might not sound all that unusual until you take into account the fact that these animals were thought to be solitary, which could indicate they may be more social than we think. Then again, it could just be prime real estate.

The two communities were found separately with Octopolis arriving first being followed by Octlantis. While we’re all for fun names, the playfulness led to some coverage around the discoveries claiming that the “cities” were “built” by octopuses. Not so, say the researchers, but instead, it shows how these animals can act as ecological engineers.

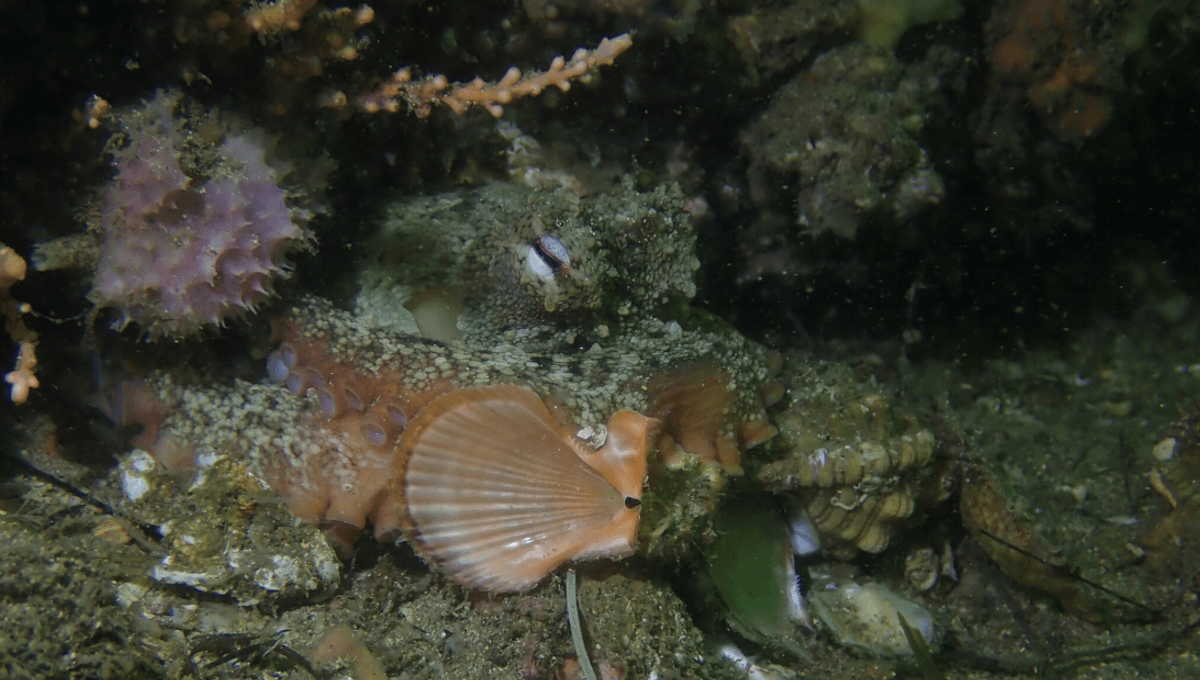

Octopolis and Octlantis are characterized by lots of burrows in a concentrated area, often reinforced with shells or anthropogenic materials like metal. The incredible intelligence of octopuses makes it easy to imagine they could design a vast, complex, shared habitat, but the bustling neighborhood is more likely an unconscious choice driven by the resources of Jervis Bay.

“This environment contains ample food for octopuses, but many predators and a paucity of good den sites,” wrote D Scheel et al. in a 2018 paper intending to set the record straight on the significance of the octopus settlements. “If one or a few good dens can be established, and these are used over years, scallop shells left at the site by foraging octopuses can accumulate and provide a better den-building material than the local soft sediment.”

“Other octopuses can eventually build dens using these shells, and those octopuses bring in still more scallops. Given the persistence of this behavior at one small location, the result is a site at which a dozen or more octopuses can build dens, and end up living in unusually concentrated circumstances.”

This kind of cumulative effect of animals interacting with and changing their environment is an example of ecological engineering. It’s not an intentional act O. tetricus studies for at college, simply a concept that can apply broadly to any organism that influences its environment.

The fairy-ring-creating Agaricus arvensis fungus was described as an ecosystem engineer for the way it fosters plant and microbial diversity in Mediterranean grasslands. It would be a push, obviously, to make out like the fungus had built a city as its influence was unconscious. While O. tetricus is a sentient creature, it’s possible their influence is equally accidental, much as we’d all like to imagine them swimming around with little hammers.

As Scheel and colleagues explained, it could well be a serendipitous form of engineering in which the octopuses’ natural behaviors and the litter they generate lend themselves well to carving out dens in the environment.

“The octopuses at Octopolis harvest the larger scallops among those available,” they explained. “While large shells could be better materials for den construction, larger scallops also provide a larger meal, and there have been large numbers of shells available at the site for quite a few years now. It is possible, therefore, that live scallops at these sites are viewed only as food, and the availability of the discarded shells for den building is a fortuitous byproduct.”

That these octopuses aren’t secretly practicing art and architecture is not a disappointing outcome, as it’s still an incredible discovery to see so many of a normally solitary animal living side-by-side. It is, however, true that it takes a bit more than a bunch of octopuses moving in together to make up a city.

“An aggregation of individual dwellings, even where each is intentionally constructed, is not a city,” concluded the authors. “A city is a center not just of population but of commerce, culture and design. Cities are cooperatively constructed and maintained communities.”

“We are not making this claim for Octopus tetricus.”

Source Link: Octopolis And Octlantis Were Created By Engineering Octopuses, But They’re Not “Cities”