Around 300,000 years ago, a family of early humans visited a lake bordered by open forest. We don’t know if they came there to drink, swim, or forage, but hunting the herds of giant beasts found there was probably not on their agenda. Their footprints not only record their presence, but place them in an ecosystem we can reconstruct from other clues.

The prints were found at the Schöningen Paleolithic site in what is now Lower Saxony, which was rescued by archaeological teams in the 1990s from an encroaching coal mine. As a new paper notes, without bones or teeth we cannot identify the species of the footprint makers with certainty. However, Homo heidelbergensis are known to have lived in Europe up to this time, while the presence of no other human species has been established in the area at the appropriate time.

Two of the three tracks at the Schöningen site are from individuals who were not fully grown, suggesting a family group coming to the lake together, and unlikely to be hunting. “Depending on the season, plants, fruits, leaves, shoots, and mushrooms were available around the lake. Our findings confirm that the extinct human species dwelled on lake or river shores with shallow water. This is also known from other Lower and Middle Pleistocene sites with hominin footprints,” said Dr Flavio Altamura of the University of Tübingen in a statement.

Stone tools and horse bones carved with sharpened stone have been found in the same area and dating to around the same time.

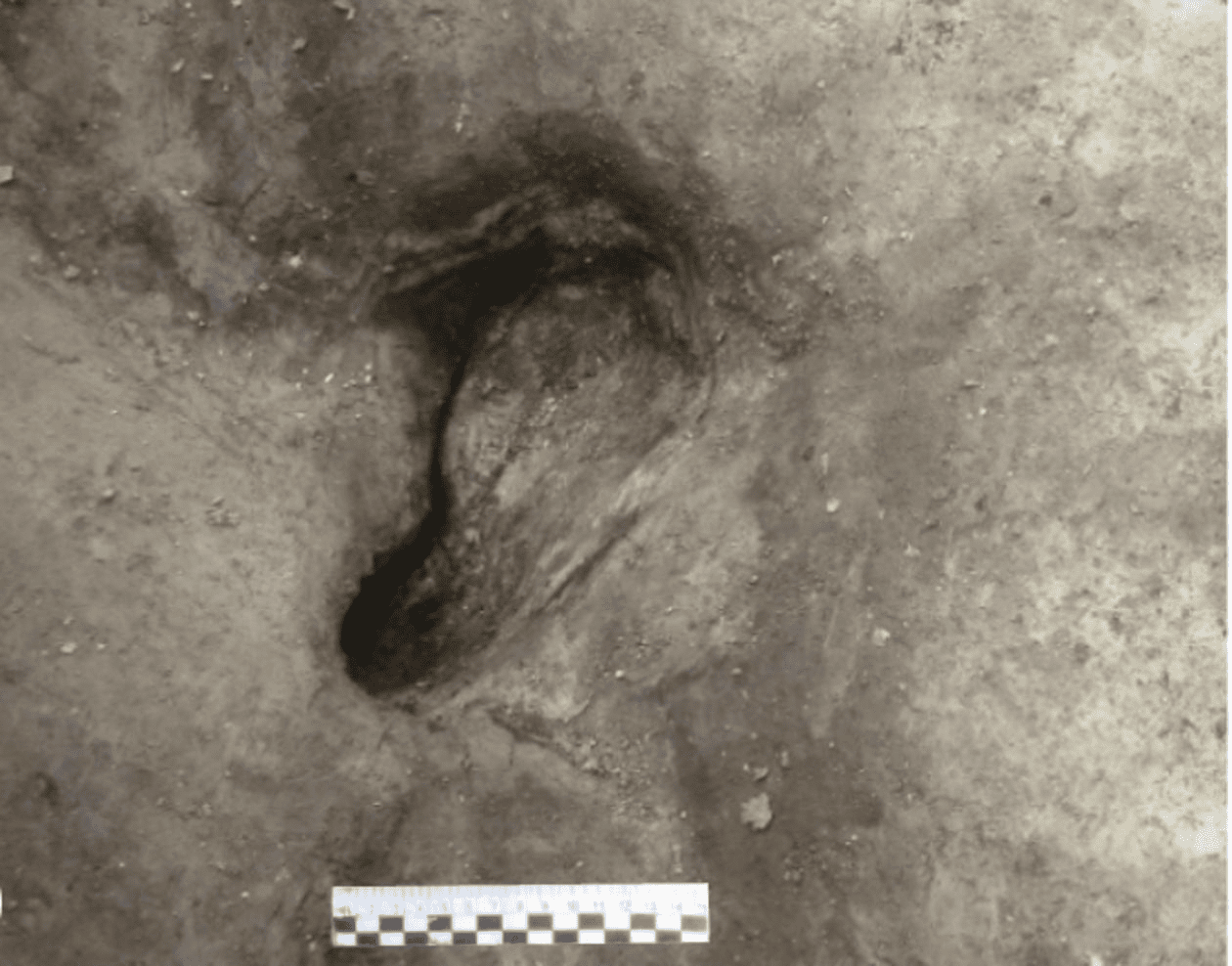

A distinctively human footprint, presumed to be H. heidelbergensis.

Image credit: Senckenberg/University of Tübingen

Other footprints at the site come from Palaeoloxodon antiquus, the straight-tusked elephant that grew to twice the size of a mammoth or African elephant. They are the most northerly Palaeoloxodon footprints ever found, and the first in Germany. We know Palaeoloxodon were hunted by Neanderthals. There is no evidence H. heidelbergensis had the same capacity, but the paper proposes an elephant found nearby had died of natural causes and been scavenged by humans.

“The elephant tracks we discovered at Schöningen reach an impressive length of 55 centimeters [22 inches]. In some cases, we also found wood fragments in the prints that were pushed into the – at that time still soft – soil by the animals,” explained Dr. Jordi Serangeli “There is also one track from a rhinoceros – Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis or Stephanorhinus hemitoechus – which is the first footprint of either of these Pleistocene species ever found in Europe.”

Fossil elephant track in Schöningen 13 II-2 with wood fragments in the footprint backfill. Much of the area was thoroughly trampled by the giant straight-tusked elephant.

Image credit: Senckenberg/University of Tübingen

Not surprisingly, such immense creatures left deep prints in the soft mud around the lake, and the authors have identified two trampling episodes, interleaved with thin peat deposits. They write, “Animal feet sunk in the peat, reaching or indirectly deforming the muddy substrate.” Much of the area is so trampled individual footprints have been lost, but in some cases tracks clear enough to identify the maker survive.

This may be hard to distinguish from an elephant print to the layperson, but it is really a rhino print of the Stephanorhinus genus.

Image credit: Senckenberg/University of Tübingen

Among these are three sets of tracks whose toes and curved foot identify them as human. One is of an adult, another a juvenile. The third is more ambiguous, and might not have been recognized as human without its proximity to the other two, but probably comes from another young individual, still some way short of fully grown.

The lakeside forests were a mix of birch, pine and grassy woodlands, providing the mixed ecosystems that suit adaptable humans seeking a mixed diet.

The paper is published in the journal Quarternary Science Reviews.

Source Link: Oldest Human Footprints In Germany Reveal Life In Saxony 300,000 Years Ago