On the evening of November 2, 1988, in a quiet computer lab at MIT, a student majorly screwed up. Robert Tappan Morris, a 23-year-old computer science student at Cornell University, had written 99 lines of code and launched the program onto the ARPANET, the early foundation of the Internet. Unbeknownst to him, he had just unleashed one of the Internet’s first self-replicating, self-propagating worms – “the Morris Worm” – and it would change the way we saw the Internet forever.

But why would a nerdy college kid unleash this beast? Even after 30 years, a criminal trial, and countless retellings of his story, it remains unclear.

Morris claimed it was a harmless exploit to gauge the size of the Internet. However, the fact he released the worm from MIT, not his own college of Cornell University, often raises questions among Morris’ detractors.

“Speculation has centered on motivations as diverse as revenge, pure intellectual curiosity, and a desire to impress someone,” according to the official report on the incident by Cornell University from 1989.

Regardless of motive, Morris made a serious blunder. Within its relatively simple programming, he made the worm far too quick, too aggressive, and too obvious.

The program snaked onto computers by asking them whether there was already a copy of the program running. If the computer responded “no,” then the worm would copy itself onto the computer. Morris wanted to avoid infecting the same machine multiple times, so the program could slip onto more computers before drawing unwanted attention. If a computer responded “yes” to the question, the worm would only duplicate itself and install another copy every one in 7 times.

However, things quickly got out of hand. The program spread quicker than Morris anticipated and his “1 in 7 safeguard” proved to be ineffective. Computers all around the globe were quickly installing hundreds and hundreds of copies in an endless loop, eventually overwhelming them through masses of unnecessary processing.

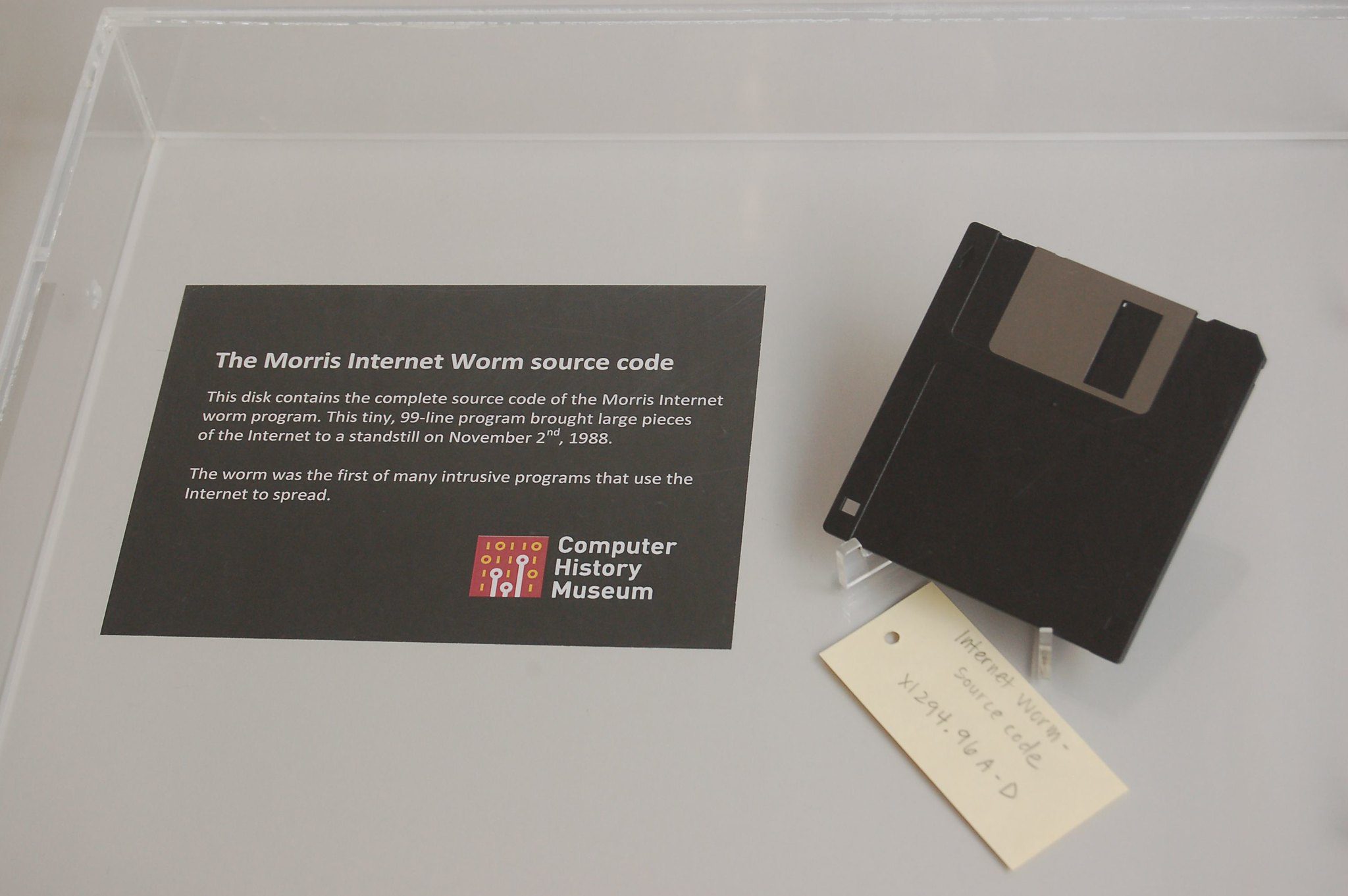

The Morris Worm source code on a floppy disk was on display at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California, US. Image credit: Intel Free Press/Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

By the morning of November 3, an estimated 10 percent of the world’s Internet-connected computers were down. MIT’s computers were hit first and hardest, but the worm quickly spread throughout the US, with reports of it reaching as far as Europe and Australia.

Needless to say, even at a time when there were just 60,000 computers, this cost a lot of cash. Estimates of the damage vary massively, but figures started at $100,000 and go upward to tens of millions.

News spread quickly that was the work of Russian hackers – after all, the Cold War was still clinging on. The papers and cable news channels lapped the story up, not least because Morris’s father was a senior figure in the computer security arm of the National Security Agency (NSA).

After the panic and confusion fizzled out, Morris was caught and charged under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. He pleaded “not guilty” – but the jury thought otherwise, sentencing him to three years of probation, 400 hours of community service, and a fine of $10,050.

In 1990, just after his sentencing, the New York Times wrote: “It did scare the wits out a lot of people who run computer systems.”

If anything, that’s an understatement. By the end of November 1988, DARPA had put forward funding for the Computer Emergency Response Team in direct response to the Morris Worm. From here on out, the Internet was no longer viewed as a placid network of wires – it was a network of ungoverned alleys filled with shady people and open doors.

“This was not a simple act of trespass analogous to wandering through someone’s unlocked house without permission but with no intent to cause damage. A more apt analogy would be the driving of a golf cart on a rainy day through most houses in a neighborhood,” the Cornell Commission report concluded in 1989.

As an ending fitting for the start, Morris returned to MIT’s computer technology department to build a career as a renowned professor. Better the devil you know, I guess.

The original version of this article was published in January 2018.

Source Link: One Evening In 1988, A College Student's Prank Broke The Internet