A new explanation has emerged for why Homo sapiens survived in Europe and North Asia when the apparently better-adapted Neanderthals did not. A variety of approaches, including ochre sunscreen and tailored clothes, may have saved them from skin cancer and weakened immune systems when a weaker magnetic field let in more radiation.

During the Earth’s history the direction of the magnetic poles has flipped at least 180 times. Never having observed it with modern technology, we don’t know exactly what happens around these flips, but there is evidence they are accompanied by a weakening of the Earth’s magnetic field and dramatic migrations of the magnetic poles. Sometimes similar weakening and movement can happen without a flip, the most recent example being known as the Laschamps excursion.

Such changes to the Earth’s magnetic field could increase exposure to radiation from space that currently gets funnelled harmlessly towards places few animals and fewer humans live. Some people like to predict catastrophe the next time such a flip occurs. However, efforts to tie past extinction events to such weakening have largely failed. A possible exception involves the Neanderthals, who appear to have gone extinct (aside from their legacy in our genes) 40,000 years ago. That coincides with the peak of the Laschamps excursion, 41,000-39,000 years ago, during around 300 years of which the magnetic field appears to have been extremely weak.

Researchers from the Engineering and Anthropology departments at the University of Michigan combined with colleagues from Finland, the UK, and Germany to explore the possible association. Their modeling indicated that during the Laschamps excursion, the magnetic north pole wandered over Europe, compared to its current location in the Arctic Ocean. This would have brought spectacular auroras to many parts of the world that had seldom seen them before.

More important than the sky lights at night, however, was what would have happened during the day. The modeling also indicates the field strength fell by around 90 percent, exposing the ozone layer to a bombardment of cosmic rays at all hours. The destruction these would have wreaked, like a more extreme version of late 20th century chlorofluorocarbon emissions, would have prevented the layer from blocking carcinogenic UV light from the Sun.

Exposed skin would have become a health risk. Excessive UV radiation exposure is associated not only with skin cancers but weakened immune systems and folate deficiency that can cause birth defects.

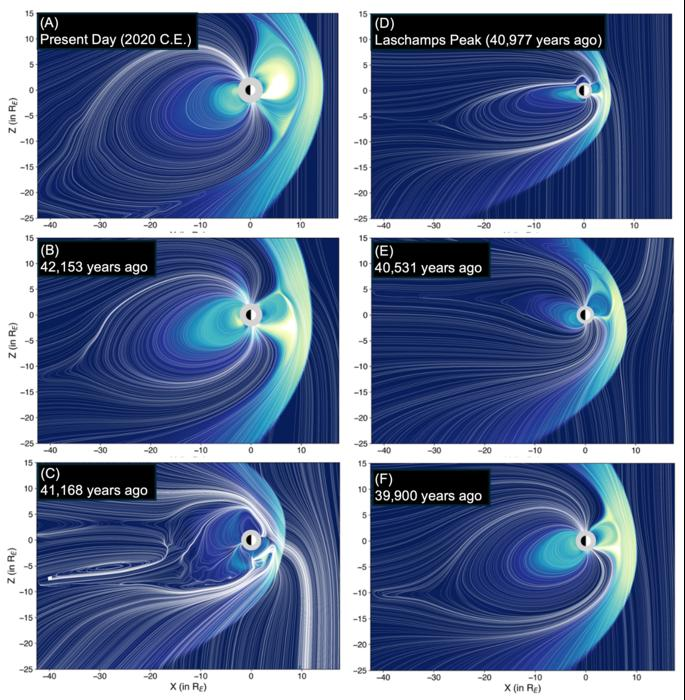

Forty-two thousand years ago (C) the Earth’s magnetic field was much like today (A), but in between it took a major dip.

The authors noted that the timing coincides with changes in H. sapiens fashion, with tailored clothing taking off. Meanwhile, this is the period when use of ochre became widespread for cave art, and possibly human adornment. Ochre provides protection against UV radiation, and is still used for that purpose in some areas, although today colorless alternatives are more popular.

“In the study, we combined all of the regions where the magnetic field would not have been connected, allowing cosmic radiation, or any kind of energetic particles from the sun, to seep all the way in to the ground,” said lead author Dr Agnit Mukhopadhyay in a statement.

“We found that many of those regions actually match pretty closely with early human activity from 41,000 years ago, specifically an increase in the use of caves and an increase in the use of prehistoric sunscreen,” Mukhopadhyay said.

Given the effect we and our ancestors have had on many species when we arrived in their territory, it was natural to suspect the first H. sapiens wiped out Neanderthals through war or competition for food. However, have learned that H. sapiens arrived in Europe around 56,000 years ago, almost 100 generations before the Neanderthals’ extinction, forcing anthropologists to seek another explanation.

“What some of the differences are between these species, between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans, that might account for that disappearance has been a major anthropological question for decades,” said Dr Raven Garvey (whose previous paradigm challenging we covered) .

More advanced clothing and a fondness for body paint might be at least part of the answer. Neanderthals wore clothes, but having been in the far north much longer than the relatively new arrivals from Africa, they probably needed them less. That might explain why needles and awls for sewing have been found at the sites of H. sapiens dwellings, but not those of Neanderthals. Whether people realized it or not, making clothing to fit would also have meant less skin exposure to sunlight, and therefore greater safety. Slip, slop, slap has an ancient history.

The authors are joining dots with this suggestion, rather than providing any direct evidence. However, at least some of their work can be tested, albeit not at a time of our choosing. The modeling of the effects of the Laschamps excursion in radiation exposure can also be used to predict future such events. It may take thousands of years, but if humans have not gone the way of the Neanderthals, and our records are intact, we will learn if the modeling used here was right.

Irrespective of how you feel about our survival prospects, we’ll need to do a good job of preserving scientific papers for that to happen. “If such an event were to happen today, we would see a complete blackout in several different sectors,” Mukhopadhyay said. “Our communication satellites would not work.” Archivists thinking about long-term preservation might want to include this paper, assuming they’re resourced for scenarios like this.

The study is published open access in Science Advances.

Source Link: Our Ancestors Knew To Wear Sunscreen – It May Be How They Survived