We are so used to the oceans being blue we use it as a signifier everyone recognizes on maps. However, the color is not inevitable, and new evidence has emerged that green was the dominant color for a long time, perhaps billions of years. Blue might just be a passing stage on the way to something else. That means anyone trying to determine whether planets host life based on their colors needs to check their assumptions.

Like the sky, water scatters light so that more blue reaches our eyes than other colors. We know that pollutants or an abundance of lifeforms can change the color locally, but it would take a lot to transform 70 percent of the planet.

However, an attempt to reconstruct the world as it was around the time of the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) suggests that indeed happened, using clues left behind in the biology of cyanobacteria.

Oxygen is a very reactive element, and in the processes that formed the Earth it became bound up with other things, leaving an atmosphere almost entirely composed of nitrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide. Around 2.4 billion years ago, although the date is heavily debated, the GOE changed that, as cyanobacteria started using oxygen-producing photosynthesis as their dominant way of capturing energy from sunlight. This oxygen accumulated in the oceans and the atmosphere, opening the way for more complex life-forms that lived by breathing it.

Today, photosynthesis is mostly performed by plants or green algae, both of which use chlorophylls. However, the cyanobacteria that caused the GOE used molecules called phycobilins as well as chlorophylls to make oxygen and sugars out of carbon dioxide and water. Phycobilins absorb light at different wavelengths from chlorophylls, and the combination can increase the energy harvested.

A team led by Dr Taro Matsuo of Nagoya University wondered why this was. After all, an extra molecule comes at a cost, so conditions must have justified it. The possibility the oceans at the time were absorbing parts of the electromagnetic spectrum that are usually transmitted today struck them as a likely explanation. If so, the light that reached the cyanobacteria, aside perhaps from very close to the ocean’s surface, would be missing certain colors, making it hard for chlorophylls alone to extract the necessary energy.

We know the oceans at the time contained large quantities of ferric iron, which precipitates in water as rusty particles. Matsuo and colleagues tested the behavior of ferric iron in water, and concluded the particles would mostly be small enough to mix through the water column, rather than sinking, as larger particles would. Ferric iron in water absorbs both red and blue light, leaving only green to reach depths of 5-30 meters (16-100 feet) where most of the cyanobacteria dwelled.

“Genetic analysis revealed that cyanobacteria had a specialized phycobilin protein called phycoerythrin that efficiently absorbed green light,” Matsuo said in a statement. Phycoerythrin transferred the energy from the wavelengths it could absorb to the chlorophylls, allowing them to make oxygen with light they would not have been able to use otherwise. “We believe that this adaptation allowed them to thrive in the iron-rich, green oceans.”

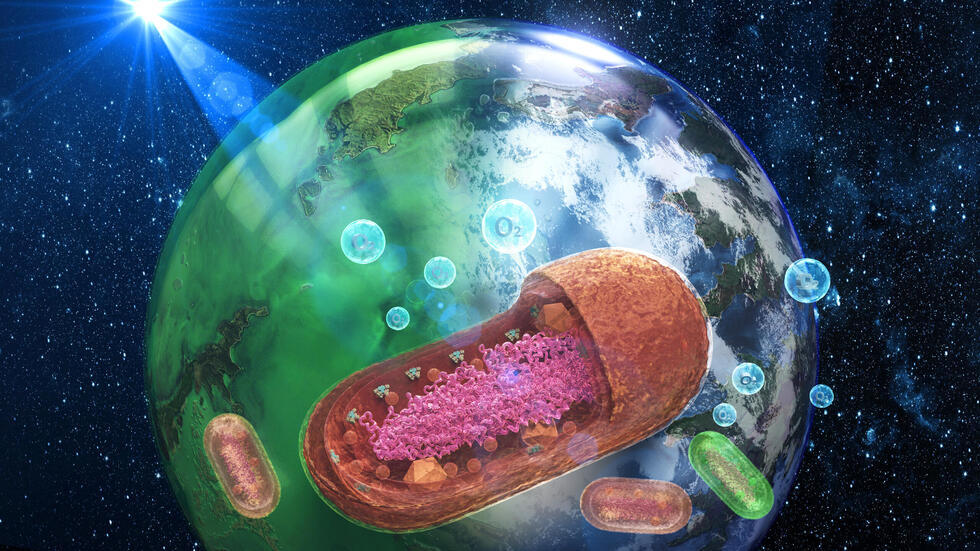

A representation of the Earth at the time of the Great Oxidation event and the cyanobacteria that were the main life-form of the time.

Image credit: Takashi Tsujino

The oceans of the day would not just have let green light in – they would also have reflected enough of it, while absorbing other colors, that an observer would have seen them as green.

“When I first had the idea that the oceans used to be green, back in 2021, I was more skeptical than anything else,” Matsuo said. “But now, after years of research, as geological and biological insights gradually came together like pieces of a puzzle, my skepticism has turned into conviction.”

Matsuo added that visiting waters off the Satsunan archipelago, iron-rich from nearby hydrothermal vents, proved particularly convincing. He and his team not only observed the bright green of the waters, but studied the light transmitted to depths and the cyanobacteria present, which Matsuo thinks are similar to those that drove the GOE.

In a Conversation article commenting on the paper, Professor Cédric John of Queen Mary University London noted other work showing that sulfur-rich oceans caused by a hotter Sun would be purple, something also considered likely for other low-oxygen planets. Today parts of the oceans are affected by red tides, as a result of extreme algal blooms, and under certain circumstances this might become a worldwide phenomenon, particularly if nitrogen pollution is not checked. A similar shade could arise from a different source if a hot and wet climate caused enough oxidized iron to be swept into the oceans.

We can’t be sure that even very Earth-like planets will go through the same processes. After all, if they orbit a slightly cooler star than the Sun, the light they receive will have less green and more orange or red. Nevertheless, it does seem likely that the sort of worlds we are most interested in will initially be rich in ferric iron, so there is a high chance that their oceans will have a similar shade for a time. We shouldn’t just be looking for more pale blue dots.

The study is published open access in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Source Link: Our Blue Oceans Were Once Green And Their Fate Could Be Purple Or Red