A treasure trove of fossilized eggs were the subject of a recent study that discovered a curious specimen among the clutch: an egg-in-egg, or ovum-in-ovo, whereby an egg is found to contain another egg. The quirk of ovulation has only previously been reported in birds, not reptiles, and so it may be that these dinosaurs had a similar laying pattern to their feathered descendants.

The 256 fossilized eggs were spread across 92 clutches in the Lamenta Formation that’s tucked in the Narmada Valley of central India. The region is famous for the Late Cretaceous specimens it’s been found to conceal, including the preservation of prehistoric eggs.

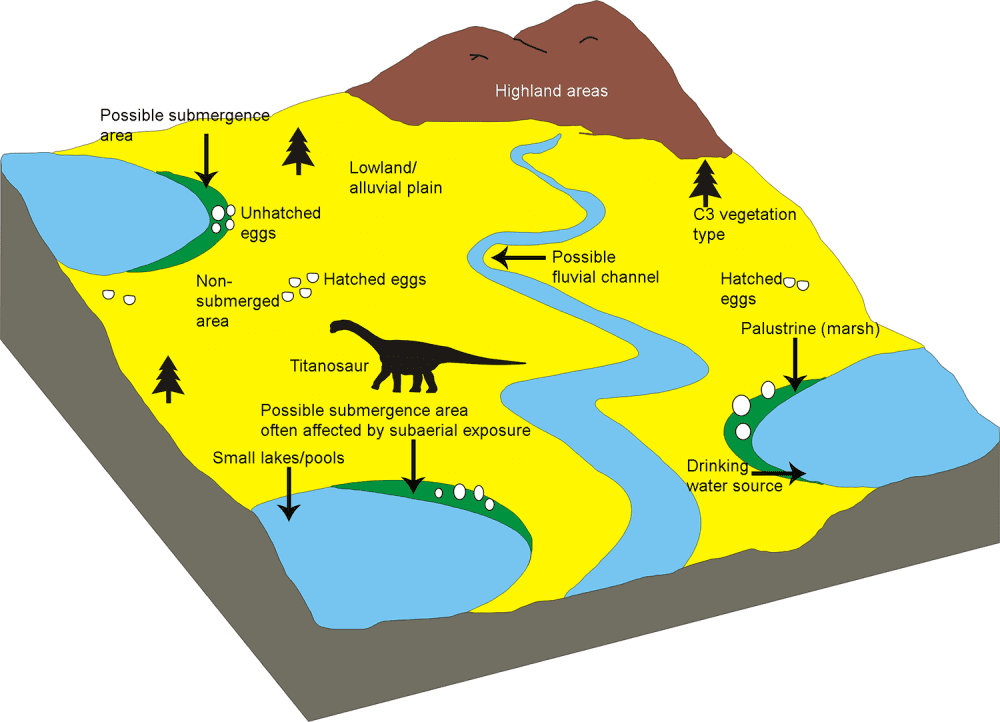

Breaking into the fossil record isn’t easy for eggs – being fragile and defenseless puts you at a high risk of being trampled or eaten. Any eggs that do so were usually helped along by a swift burial after being laid and landing in the right environment.

Those that do survive have enormous potential, academically speaking, telling us about the parental strategies of dinosaurs, the evolution of egg-laying, and past environmental conditions. The researchers on this particular study were also treated to a rare shiny of fossilized eggs.

“The most surprising discovery was of a pathologic egg called ‘ovum-in-ovo‘ where an egg within an egg was observed,” study author Dr Harsha Dhiman told IFLScience. “Such eggs have not been reported from reptiles but only from birds. This discovery has led us to hypothesize that titanosaur sauropod dinosaurs may have laid eggs in a sequential manner as is the case with birds.”

Another bird-like discovery was the sheer number of nests in one area, comparable to the colonial nesting behaviors seen among many groups of modern birds. However, the burial of the eggs in shallow pits was more reptile-like, mirroring the behavior of modern crocodiles.

The pattern in which they were laid also tells us about the possible parenting strategies of these dinosaurs.

“Some of the nests were found within a close distance of each other,” continued Dhiman. “This may point to lack of parental care since maneuvering around the eggs by the parents would have trampled the eggs considering the size of an adult titanosaur sauropod. Moreover, lack of parental bones in association with fossil eggs may also indicate that parental care was not involved.”

The authors identified six different egg species among the 92 clutches. This came as somewhat of a surprise as it paints a picture of biodiversity in the region that hasn’t been reflected by the skeletal remains dug up here.

The discovery points towards an extensive hatchery of titanosaur sauropod dinosaurs in the Narmada Valley, making it a treasure trove of specimens and academic insights that could teach us new things about what conditions favor nest preservation and how these dinosaurs reproduced.

Dhiman and colleagues certainly aren’t done with the field study site just yet:

“We hope to carry out more field work in the area in order to look for any potential sites that may have preserved fossilized adult or juvenile bones for a precise taxonomic identification of the eggs and for understanding the preservational milieu. We also aim to do CT scans of some potential eggs to look for preserved embryos or hatchling bones.”

The study was published in PLOS ONE.

Source Link: Over 250 Fossilized Dinosaur Eggs Found In India, Including Rare Egg-In-Egg