If you’d looked to the sky in the right part of Idaho back in the late 1940s, you might’ve been lucky enough to spot a parachuting beaver. The unconventional approach to wildlife management came in response to conflict that was emerging between native beavers in southwest Idaho and the increasing prevalence of an invasive species: humans.

We don’t always get on well with beavers owing to our love of trees and flowing water: two things beavers have a lot to say about. Felling trees allows beavers to build dams, transforming slipstreams into waterlogged wetlands, which they’re far better adapted for. Unfortunately, that goal clashes with humans who prefer drier dwellings.

As US residents migrated away from cities and farther into the wilderness, the Idaho Fish And Game Department (IFG) could see that the “beaver problem” they’d been managing since the 1930s was only going to get worse. However, exterminating the animals wasn’t a desirable option either as beavers provide valuable ecosystem services, engineering an environment that promotes water quality and biodiverse habitats, and reduces the risk of erosion.

Armed with nothing but some beavers, a dream, and a pocketful of parachutes, they hatched an idea.

In a 1950 document titled “Transplanting Beavers By Airplane And Parachute,” IFG employee Elmo Heter explained why more conventional methods of transplanting beavers had failed in the past, describing it as “arduous, prolonged, [and] expensive” with “high mortality among the beavers”.

After being packed on horses, beavers were exposed to direct heat from the Sun for days on end, which resulted in them being unable to eat, growing increasingly “belligerent”, and – too often – dying. “It was evident that a faster, cheaper, and safer method of transportation was a vital need,” he wrote. “The use of planes and parachutes has filled that need.”

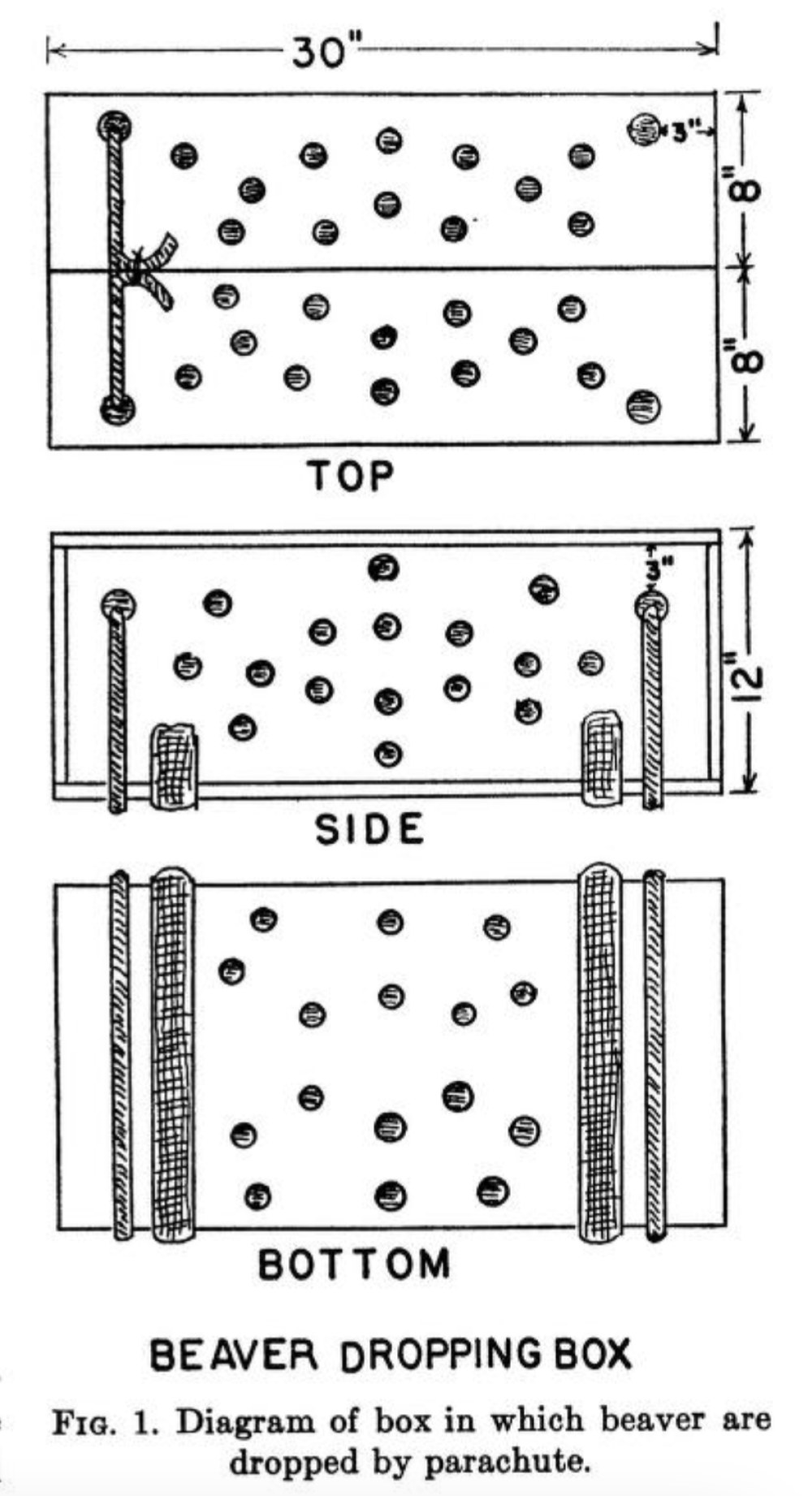

Before releasing their Navy Seal beavers, the IFG trialed dummy weights to establish that – serendipitously – a surplus of 7-meter (24-foot) rayon World War II parachutes were most satisfactory. It seemed the US state could deal with a surfeit of beavers and WWII parachutes in one fell swoop, pun intended.

Pairs of beavers were packed in boxes and carried by a single chute, which came with the benefit of needing half as many, while also reducing the chances of the beavers relocating the second they landed as having a buddy along seemed to encourage them to stick around.

Parachuting beaver boxes proved to be cheaper and less deadly than carrying them for days on horseback.

“One old male beaver, whom we fondly named ‘Geronimo’, was dropped again and again on the flying field,” wrote Heter. “Each time he scrambled out of the box, someone was on hand to pick him up. Poor fellow! He finally became resigned, and as soon as we approached him, would crawl back into his box ready to go aloft again.”

“You may be sure that ‘Geronimo’ had a priority reservation on the first ship into the hinterland, and that three young females went with him. Even there he stayed in the box for a long time after his harem was busy inspecting the new surroundings. However, his colony was later reported as very well established.”

Geronimo’s maiden flights paved the way for a payload of 76 live beavers to take flight in the fall of 1948, resulting in just one casualty that was – not to victim blame – possibly the beaver’s fault. After release, a cable came loose creating a small enough gap in the box for the beaver to stick its head through and escape onto the top of the box.

“Even so, had he stayed where he was, all would have gone well,” continued Heter, “but for some inexplicable reason, when the box was within 75 feet [23 meters] of the ground, he jumped or fell from the box.”

RIP.

The beaver drop method was later analyzed, where it was revealed that the parachute method was cheaper than the previous method at around $16 per beaver, while also reducing the number of beaver deaths and hours of manual labor needed to complete the journey.

And if you think that’s nuts, just wait until you hear why they started parachuting wolves in Michigan.

Source Link: Parachuting Beavers Were A Surprisingly Successful Conservation Strategy In The 1950s