If you are of the sort of human who follows science news, you are probably aware that lately there has been a lot of discussion of tails lately, courtesy of our latest interstellar visitor comet 3I/ATLAS.

That comet has developed a tail and a rare (but perfectly normal) anti-tail during its brief tour of our Solar System. But comets are not the only objects that develop tails. As the good people at EarthSky recently highlighted, the planet Mercury has a tail. This got us wondering; maybe people are unsure whether the Earth has a tail as well? The answer short answer is yes, and it stretches at least 2 million kilometers (1.2 million miles) into space behind our planet.

Let’s start with the easy one. Mercury has a razor-thin atmosphere, but it does contain small amounts of sodium within it, which can be pushed around by the dauntingly close Sun.

“Scattered sunlight gives the sodium a bright orange glow. This scattering process also gives sodium atoms a push – this ‘radiation pressure’ is strong enough, during parts of Mercury’s year, to strip the atmosphere and give Mercury a long glowing tail,” NASA explains. “Someone standing on Mercury’s nightside at the right time of year would see a faint orange similar to a city sky illuminated by sodium lamps!”

That’s Mercury out of the way, now onto Earth’s tail. This one is a little less obvious than the sodium tail, but is nevertheless there, tailing behind us on the Earth’s night side.

Every macro object, from actual magnets to bizarre Antarctic animals which can live for 11,000 years, is a little magnetic thanks to the spin of their electrons generating magnetic dipole moments, like teeny tiny magnets. In most materials these spins are not aligned and cancel each other out, leaving you with little net magnetic charge. But in magnetic materials they can align in the same direction and the result is a magnet, with a magnetic field and north and south poles.

Earth has its own magnetic field, powered by geodynamic processes in the outer core, and the movement of molten iron and nickel.

“The region laced by Earth’s magnetic field, called the magnetosphere, dominates the behavior of electrically charged particles in space near Earth and shields the planet from the solar wind,” NASA explains, adding that the magnetosphere traps plasma, or electrified gas.

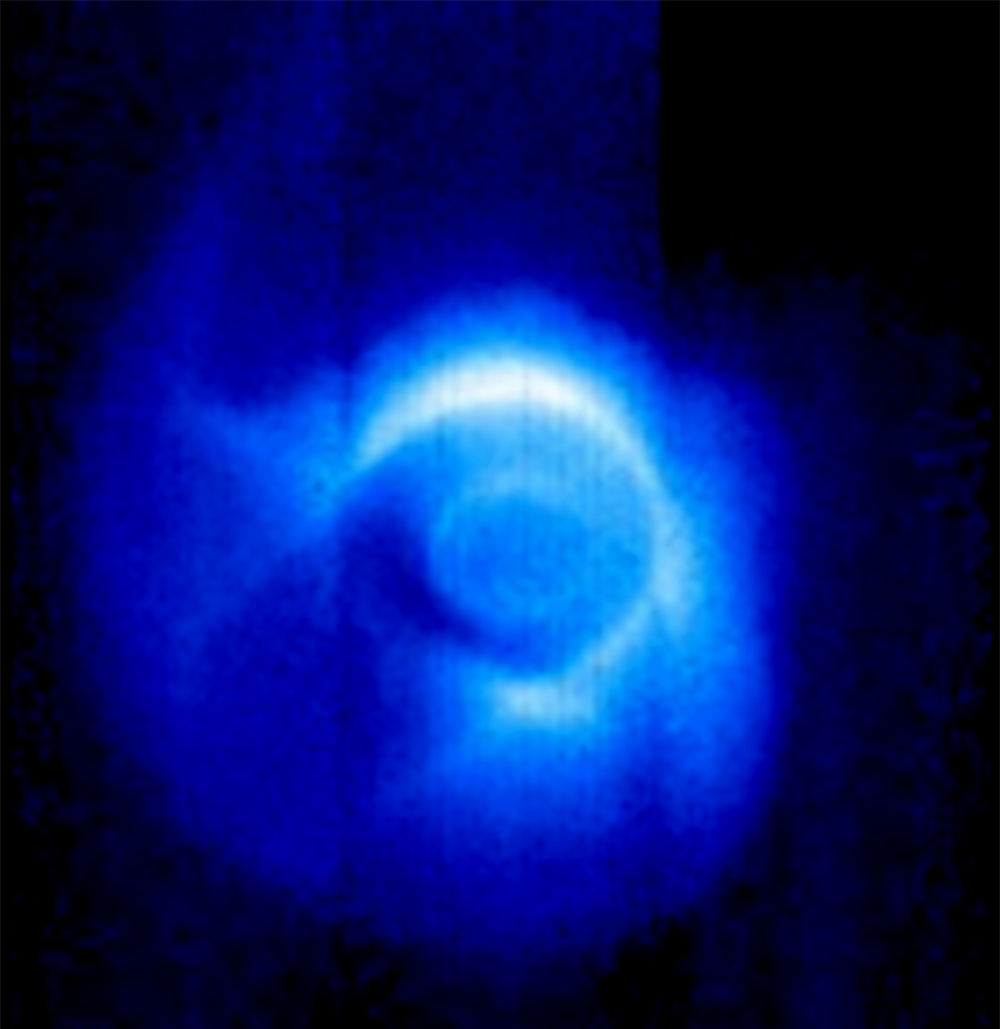

Full view of Earth’s plasma tail, captured by NASA’s Imager for Magnetopause to Aurora Global Exploration (IMAGE).

The Earth’s magnetosphere traps electrified gas, called plasma, and it is this which forms the Earth’s tail as some of the plasma streams towards the Sun.

“The tail structure is believed to be a return flow of plasma that occurs when the solar wind (a plasma flow ejected continuously from the solar surface) buffets the magnetosphere and distorts its shape. For example, at first a falling raindrop is roughly spherical. As it falls and gains speed, air resistance causes the droplet to change shape as water is dragged from the bottom (head) to the top (tail). Surface tension prevents most of the water from simply dispersing from the tail, so it is forced to flow within the raindrop and return to the head,” NASA adds.

“The solar wind distorts the Earth’s magnetosphere in a similar way, compressing it on the Earth’s day side, like the head of a raindrop. The region is stretched on the night side, like the raindrop tail, forming a teardrop shape.”

The Earth’s tail is known as the “magnetotail”. Though it is generally a permanent feature, it is at the whims of the solar wind; in April 2023, for example, a particularly strong coronal mass ejection (CME) knocked Earth’s tail off, replacing it with Alfvén “wings”.

“The Earth typically moves in the magnetized solar wind with super-Alfvénic speeds, generating a bow shock, magnetosheath, and a windsock-like magnetosphere with a tail,” a paper on the effect of that CME on Earth explains.

“Occasionally and especially in the strong magnetic fields of the Sun’s coronal mass ejections, the Alfvén speed exceeds the solar wind speed (sub-Alfvénic). MHD simulations have shown that during long duration (>1 hr) sub-Alfvénic solar wind, Earth’s magnetosphere transforms into Alfvén wings.”

Though there is flux in the size and shape of the magnetosphere, it is thought that the solar wind drags out our magnetotail to possibly 1,000 times the Earth’s radius. It remains pretty difficult to know exactly how far it extends.

“Although our Earth’s tail has been explored by numerous spacecraft over the past few decades, many mysteries remain,” the European Space Agency explains. “This is mainly because the magnetotail is so large – it stretches at least two million kilometres into space on the night side of the Earth. Single spacecraft cannot hope to discover the secrets of this vast region.”

Source Link: People Are Just Now Realizing That The Earth Has A Tail, Stretching At Least 2 Million Kilometers