Science fiction writers once imagined Venus as a world of oceans or swamps underneath all that cloud. It’s possible they were not so much wrong as very, very late. Modeling suggests the planet closest to Earth in size and distance from the Sun may not only have oceans, but they could have survived for more than a billion years.

When large asteroids collide with a rocky body, some of the rocks they throw up escape into space, often eventually colliding with another planet or moon. The discovery of meteorites that originate from Mars, and evidence for ancient Martian oceans, has raised occasional speculation that life might have begun one planet out, transferring to what became a more hospitable home on Earth. For a brief period, Mars may have been the planet more suited to life.

Venus has greater gravity than Mars, and a much thicker atmosphere, so it would have taken a lot more to knock some rocks loose. Nevertheless, meteorite exchange is possible. What would make that really interesting is if Venus was once a place where life could have developed, rather than the hell hole it is today. A paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences concludes that might be unlikely, but not impossible, with potentially a large overlap with the era of life on Earth.

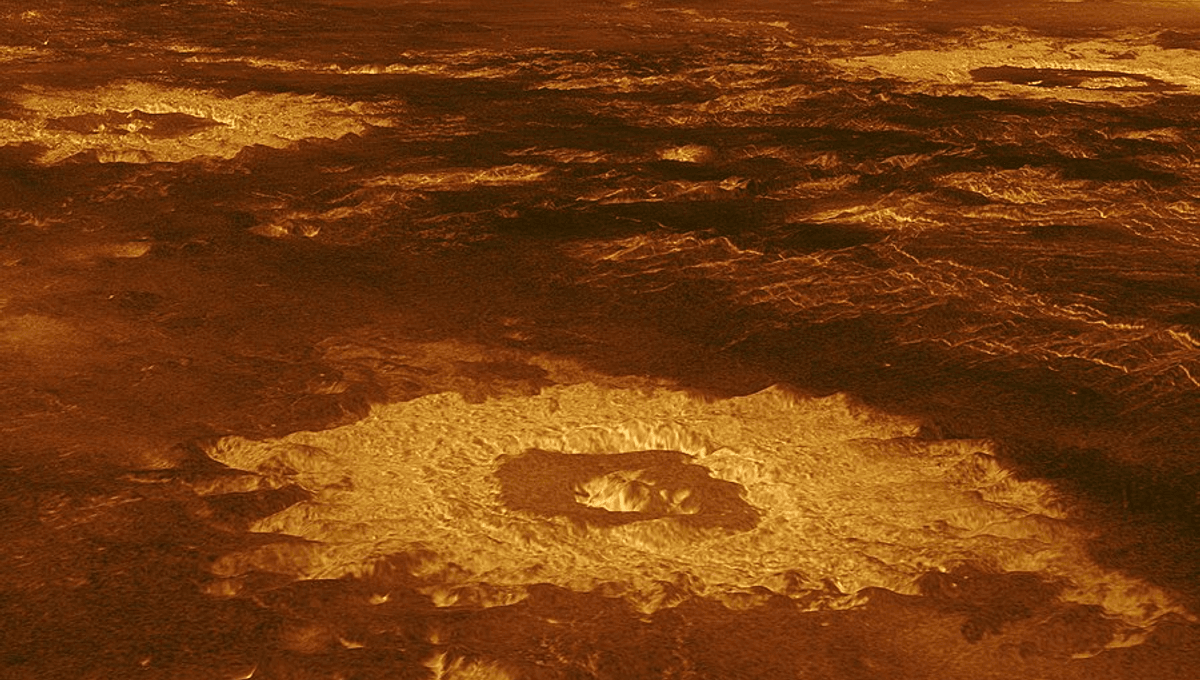

Venus is a hard place to study since the clouds block most observations from space and probes entering the atmosphere don’t last long in temperatures that can melt lead. Consequently, missions there have been few and far between. However, as University of Chicago PhD student Alexandra Warren and her supervisor Professor Edwin Kite note, that’s set to change in the next decade, and the driving reason is to find out if Venus also had a habitable period.

Warren and Kite get in first by considering the question of how much water Venus might once have had before its runaway Greenhouse effect made it so hot. They note one thing we have learned about Venus’s modern atmosphere is that it has a deuterium to hydrogen ratio 150 times that found on Earth.

Having been formed from the same material as Earth, it’s unlikely Venus started out with extra deuterium. Instead, the ratio presumably reflects the fact that hydrogen, being lighter, escapes much more easily from a planet’s atmosphere than deuterium. A ratio like that indicates Venus once had a lot of hydrogen, which was probably bound up in water.

Warren and Kite acknowledge the deuterium/hydrogen ratio doesn’t prove the water was all there at once – perhaps comets delivered a lot of both over time, and the hydrogen slowly escaped. However, they note the oxygen in Venusian water could not have escaped the same way – it must have been removed by reactions with surface rocks.

They used this fact to model various scenarios for the original amount of water on Venus and its rate of removal and see which ones match the modern atmosphere. Concentrations of argon provided a further constraint.

Of all the scenarios that the pair fed into their model, only 2.6 percent produced something that matches what we know. These provide a range of quantities of sizes for the initial ocean, if there was one, and its survival time. At maximum, they conclude Venus had enough water to cover its entire surface to a depth of 500 meters (1,650 feet) if it was smooth. Given how rough Venus is, that makes plenty of opportunity for large ocean basins and exposed land. These could have lasted until 3 billion years ago.

The figure is a maximum. It’s possible Venus was always dry, or that it had smaller oceans that disappeared quickly. Hopefully, future missions will be able to tell, but in the meantime, we can dream of a time when three planets in our solar system had oceans, and asteroids splashing down in one carried living organisms to the others.

The paper is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

[H/T: phys.org]

Source Link: Possible Oceans Of Venus Might Have Overlapped With Life On Earth