Face blindness – perhaps, like one participant in a new study, you “didn’t know it was a thing”. But prosopagnosia, to use its medical designation, is a real condition that affects someone’s ability to recognize faces, even those most familiar to them. To try to understand its impact, researchers have now surveyed 29 UK adults with prosopagnosia to get to grips with the question: What’s it like to live with face blindness?

The 29 participants (19 women and 10 men) had previously contacted the team, seeking to get involved in research because of their own face recognition difficulties. These difficulties were confirmed using objective testing – all of these people really did have prosopagnosia, to varying degrees.

It’s not known precisely how many people have developmental prosopagnosia, but the prevalence is thought to be somewhere around 2-2.5 percent.

It’s been observed to have a hereditary component, and it can co-occur with other neurodevelopmental conditions like autism. There are also acquired forms of the condition that happen as a result of injury or brain damage – one study even suggested it could be linked to COVID-19 in a small number of cases. But currently, there’s no genetic test or other diagnostic biomarker that can reliably diagnose it.

In fact, the authors point out in their paper, “In the UK, and much of the rest of the world, it is almost impossible to obtain a diagnosis of [developmental prosopagnosia] from a medical professional.”

For people living with prosopagnosia, it can have a very significant impact. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke suggested it can be “socially crippling”. In an effort to understand their experiences better, the study authors conducted in-depth surveys with the participants about how their condition affects their everyday lives; they believe this is the first study of its kind.

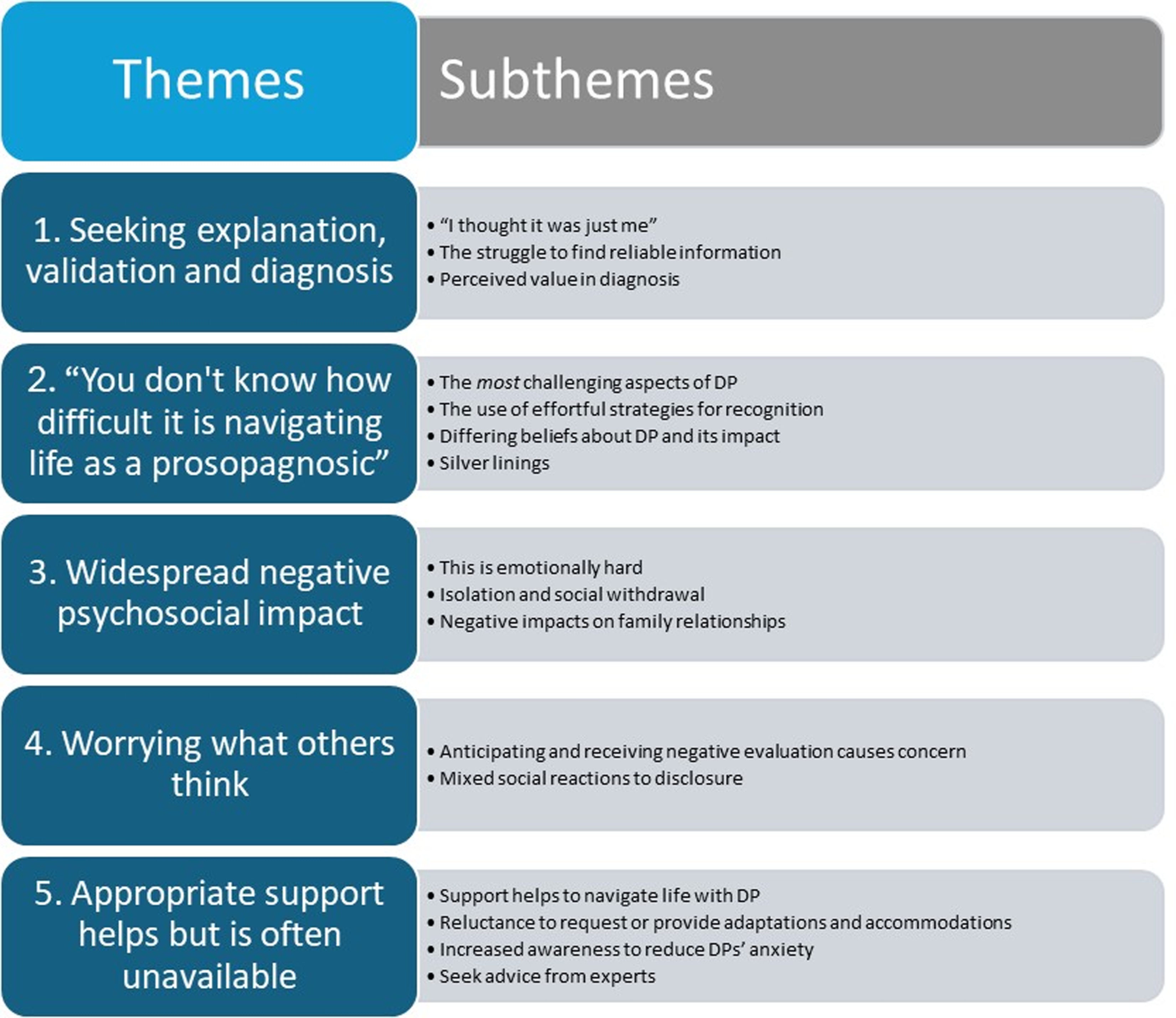

Five main themes emerged from the responses, touching on the experience of seeking a diagnosis and support, the difficulties of living with prosopagnosia, and concerns about the reactions of others.

The themes and subthemes that emerged from the participants’ responses.

Many of the responses give moving accounts of the difficulties prosopagnosia can cause when it comes to forming relationships, even with those closest to us.

“Forty-one percent of participants reported that they were unable to reliably recognise their three closest friends out of context, and around 35 percent reported being unable to recognise immediate family,” the authors report.

“Whilst I see faces and their features, they do not stay in my mind and I cannot easily see their face in my mind until it has permanently imprinted on my brain. I can just about recall the faces of my children but that is all. Everyone else has a blank face in my mind,” one of the participants described, when asked if they can recognize close friends and family.

“My husband who I have been married to for 20 years, surprised me at the airport and I didn’t recognise him,” said another.

Participants were largely reluctant to discuss their face recognition difficulties with doctors, colleagues, and even family members. Some said acquaintances and relatives had been dismissive when they had tried to explain their condition, while others spoke of the support they had received: “There’s this one colleague who understands and says ‘Hello, it’s [his name]’ every single time we meet – and every single time I am grateful. This is too awkward for most people.”

Only 34 percent of the participants had sought formal testing or diagnosis, and many believed that this would not be worthwhile. Only one person had received a diagnosis from another researcher prior to the study, while three others had been told they met the criteria for developmental prosopagnosia.

As well as describing their experiences, participants were asked what areas they would prioritise for future study. Key themes that emerged included improving awareness in the general public and increasing access to diagnosis.

One possible recommendation the authors put forward is for prosopagnosia itself to be recognized as a form of neurodivergence.

“Get it recognised by HR professionals as on a par with neurodiversity and provide advice on how they can get managers to understand the condition and what people need at work – and that they are not stupid or rude when not recognising anyone,” said one participant.

It’s clear that the experience of living with prosopagnosia differs massively between people, and that we still have a lot to learn about this condition.

“I could easily walk past pretty much anyone I knew except possibly my husband and children,” one participant explained. “It is isolating and exhausting living in a world of strangers.”

The study is published in the journal PLOS One.

Source Link: Prosopagnosia: What’s It Like To Live With Face Blindness?