A giant planet twice the mass of Jupiter has been detected after previous searches failed to find it. The planet was predicted to explain swirling arms within the protoplanetary disk around a very young star, but was missed because its light is at unexpectedly long wavelengths. Just as the planet’s discovery solves the spiral arms mystery, its redness creates a new one, with some interesting possible explanations under investigation.

Point a powerful enough telescope at the sky and sometimes you will find an object with a bright center surrounded by spiral arms. Normally this will be a galaxy with a structure like that of our own Milky Way. If you’re operating in the infrared, however, you might be looking at a star so young it’s still surrounded by its protoplanetary disk, the gas and dust from which its planets will eventually form.

Of the 29 suitably young stars close enough for detailed study, eight have distinct spiral arms within their disk. These have been attributed to the gravitational influence of giant planets that formed before the rest of the system coalesces. Proving this has been difficult, however, including for MWC 758, a star system 500 lightyears away in Taurus. Now, however, a paper in Nature Astronomy announces the discovery of MWC 758c.

The arms of spiral galaxies form without any giant gravitational fields to shepherd them, but models of protoplanetary disks indicate apparently similar structures should require a planetary initiator. This then influences the way smaller objects coalesce – Jupiter probably shaped the Earth and other inner planets this way. A possible planet, MWC 758b, was discovered in 2018, but subsequent observations failed to confirm it. The lack of a shepherding planet has been such a troubling problem that several papers have been written trying to work out where it is lurking after a decade of observations.

The discovery was finally made using the Large Binocular Telescope (LBT) Interferometer at Mount Graham, Arizona. The LBTI is unusual among Earth-based telescopes in that it can see well into the infrared, as well as at optical wavelengths.

In visible light, a planet like this one is so outshone by its star we have little hope of seeing it. However, in the infrared, the difference is less dramatic. This has allowed us to spot a number of newly-formed giant planets still hot from their formation.

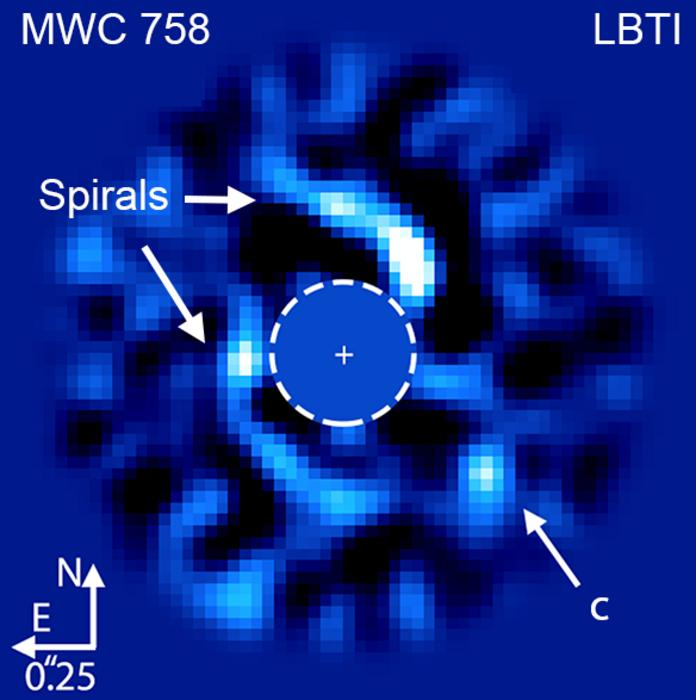

Large Binocular Telescope Interferometer (LBTI) image of MWC 758 system in infrared wavelengths. C points to the suspected planet MWC 758c, thought to be driving the formation of at least one of the spiral arms.

Image Credit: K. Wagner et al.

To see MWC 758c, however, the authors had to look at longer wavelengths than has been required for other such emerging planets. It doesn’t get bright until even further into the infrared than any planet we have seen before, and its discoverers want to know why.

“We propose two different models for why this planet is brighter at longer wavelengths,” said Dr Steve Ertel of the University of Arizona in a statement. “Either this is a planet with a colder temperature than expected, or it is a planet that’s still hot from its formation, and it happens to be enshrouded by dust.” Dust absorbs shorter wavelengths more than longer ones, and makes objects look redder than they are.

If MWC 785c is cold (relatively speaking, the light is consistent with being about 200°C (392°F)) it would upset much of what we think we know about planet formation. It might also offer a chance to study carbon chemistry in a planet cold enough to have water clouds in its atmosphere.

Being surrounded by dust would be less surprising, but interesting in a different way. Some of the encircling dust might end up settling on MWC 758c and making it larger, but some could go into forming moons like Jupiter’s big four. It would be exciting to be able to watch the process in action.

Time has been granted on the JWST in 2024 to look at MWC 758 and hopefully settle the question.

The paper is published in Nature Astronomy.

Source Link: Reddest Planet Ever Seen Explains Newly Forming Star System’s Spiral Arms