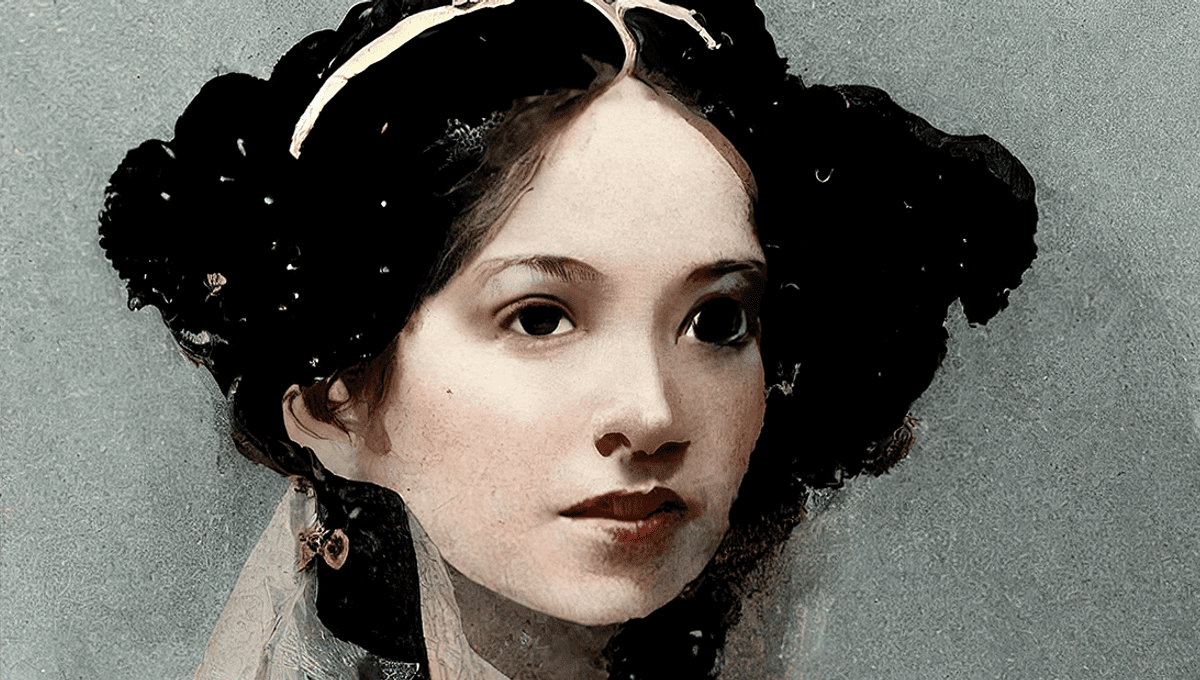

A letter from the world’s first computer programmer, Ada Lovelace, to her collaborator and creator of the first digital computer, Charles Babbage, has been widely shared on Twitter, due to its relatability regarding several paragraphs begging Babbage not to mess around with her math.

Polymath Charles Babbage is often hailed as the “father of computing”, basically because he was. The mathematician, engineer, and inventor designed the Difference Engine, which, though it was never fully built in his time, was a digital device, capable of storing and carrying out complex mathematical equations.

In the 1830s, he developed plans for the Analytical Engine, the real forerunner of the modern computer. The device, which was also not built in his time, was to be fully programmable using punch cards. In many ways, including planned storage space and the ability to use basic “if this then that” logic, it was ahead of computers that were built right the way up to the 1960s. When it was built in 2002, it was found to work as intended.

Mathematician Ada Lovelace met Babbage at Cambridge University, where he was a professor, and became extremely interested in his Difference Engine. They struck up a working relationship, and the two regularly wrote to each other and visited, discussing the Difference Engine and its successor.

Lovelace earned her (deserved) nickname as the first computer programmer through an odd route. When Babbage was attempting to finance his Analytical Engine, he gave a lecture in Turin in 1842. This was attended by the future Italian Prime Minister Luigi Menabrea, who transcribed the lecture to be published.

Lovelace, who was supporting Babbage in his attempt to get the engine financed, was asked to translate the lecture into English for publication in the UK. She did this, but while she was at it she also attached her own extensive notes, elaborating on the work. One of these notes went into detail on how the Analytical Engine could be used to calculate Bernoulli numbers, essentially writing the world’s first computer program to do so.

The two continued to correspond for 42 years, with him dubbing her the “enchantress of numbers”. She was less impressed with his numbers, as one correspondence shows.

The letter details that “note B” had taken her a lot of time and thought, because of minute considerations she had to make. Then Lovelace pivots, telling Babbage “I wish you were as accurate, & as much to be relied on, as I am myself”, adding that Babbage added to her trouble “not infrequently”.

“By the way, I hope you do not take it upon yourself to alter any of my corrections,” she continued.

“I must beg you not. They all have some very sufficient reason. And you have made a pretty mess & confusion in one or two places (which I will show you sometime), where you have ventured in my [manuscripts] to insert or alter a phrase or word; & have utterly muddled the sense.”

It’s not the first time Babbage sent his “corrections” to someone who didn’t necessarily want them. Sir, don’t mess with Lovelace’s math.

Source Link: Relatable Ada Lovelace Letter Shows Her Begging Charles Babbage Not To Mess With Her Math