It was October 1963, and France was in love. With whom? A young explorer and aviatrix, named Félicette, who had just made history as one of the very first non-US, non-USSR astronauts to get out to space and come back again.

It was the kind of story that seems almost perfectly designed for the silver screen: she was living on the streets when the French space agency found and recruited her; she beat out a dozen competitors for the job, and it wasn’t even public until she got back that she had been a girl the whole time. And best of all? She did the whole thing in a tuxedo.

Why? Because Félicette was a cat.

The training of C341

Félicette was far from the first animal in space – but she was the first cat. It was an odd choice by France’s Centre d’Enseignement et de Recherches de Médecine Aéronautique, or CERMA; depending on which side of the iron curtain you stood, the preferred species to shoot off the planet was either capitalist apes or comrade dogs.

But cats came with an advantage. “The cat was one of the animals widely used for neurophysiological studies at the time, particularly for the study of sleep and attention,” explained Michel Viso, former head of exobiology at the Centre national d’études spatiales, or CNES, in 2017. “Civilian and military scientists therefore naturally chose an animal whose physiological characteristics were very well known to test its behavior during space flight.”

They also were, frankly, easy to acquire: CERMA was able to “recruit” 14 feline hopefuls simply by scooping up strays on the rues and boulevards of Paris. None were named – it was thought that by giving the kitties ID numbers instead, the scientists involved would be able to maintain a clinical distance from their charge.

The clowder was taken to a kind of puss-in-bootcamp. They were confined in small spaces to simulate the cramped conditions of a spacecraft – probably not fun for previously semi-wild animals – and subjected in a loud centrifuge to G-forces almost twice those experienced by the Apollo astronauts on their way to the Moon. Only six cats made it through to the final round.

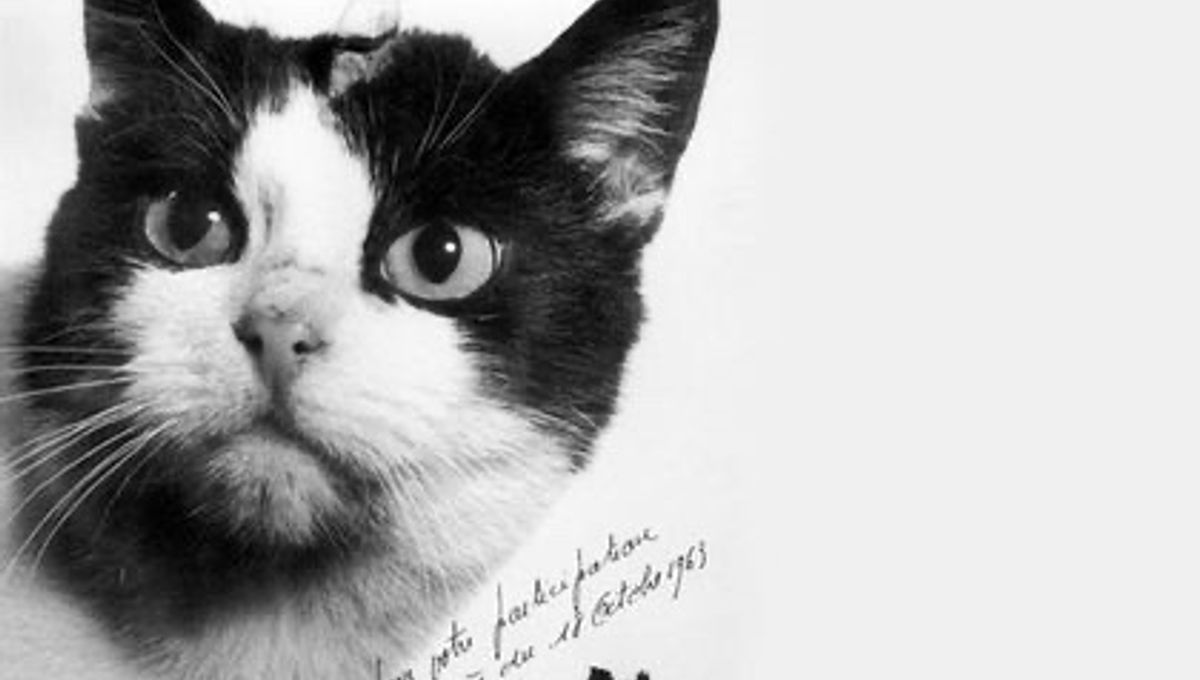

Eventually, that number was whittled down to just one: a small, black-and-white moggy labeled C341.

Where no cat has gone before… or since

On October 18, at 8.09 am local time, a Veronique rocket was launched into space from France’s first space launch and ballistic missile testing facility, the Centre Interarmées d’Essais d’Engins Spéciaux in Hammaguir, an Algerian village in the northwest corner of the Sahara Desert. On board: the world’s first ever feline astronaut.

Okay, it sounds cooler than it was. The Veronique looked, to put it gently, more like an oversized dart than anything else; it weighed less than a modern SUV, and an average height person could have wrapped their arms completely around it. They were “sounding rockets,” Viso explained, and “not powerful enough to put capsules into orbit.”

Nestled inside the craft, blithely unaware of her impending place in the history books, was C341. She had been hooked up cyborg-style: there were nine electrodes implanted on her skull and more on her legs; she was wearing microphones to monitor her breathing, and other devices recorded her heart rate throughout the mission. She spent the whole time being regularly electrocuted.

It can’t have been fun. But “the goal of all this was to understand how animals function in microgravity and to draw general conclusions about physiology, the set of physicochemical interactions that occur within an organism,” Viso explained.

“At that time, microgravity analyses offered a new window on the mechanisms regulating major functions such as blood circulation, respiration, reproduction, and coordination of movements.”

It took 42 seconds of rocket engine burning – and 9.5g of acceleration on poor little C341’s body – for the cat to slip the surly bonds of Earth. Her little craft made it almost 157 kilometers (98 miles) away from the ground – 57 kilometers (35 miles) past the accepted “edge of space” – before its return.

More acceleration, a parachute deployment, and a few minutes of hanging upside-down with her butt in the air waiting for rescue, and C341’s mission was over. In total, she’d been “in space” for only about five minutes, and she never even got to enjoy the view.

But now, she was a hero.

Becoming Félicette

The project had been a success; the astronaut had survived; it was finally safe to alert the press. They took the story and ran with it, dubbing the pint-sized traveler “Félix” after the famous cartoon character – but CERMA protested. Félix wouldn’t do, they pointed out: this lady was Félicette.

Unfortunately, though, the conclusions of stories about animals in space are rarely happy – and Félicette’s is no exception. Two months after her safe return, she was euthanized so that scientists could examine her body for any physiological or anatomical damage from her flight – an effort that they would later admit had provided no useful information at all. No more cats would ever make it into space, and all but one of Félicette’s fellow recruits were put down (the last one, Scoubidou, became a mascot for the agency after suffering complications from the electrode surgery. Every cloud has a silver lining, it seems).

But there is a light at the end of this tunnel. While animals are still pretty routinely sent into space, there are much more stringent rules around doing so – making such missions more comfortable and less fatal than what Félicette and her contemporaries had to endure.

“In the 60s, scientists and engineers were primarily concerned about how dangerous it might be for a human to be in a capsule in outer space, and most animal space flights were undertaken to see if they suffered or their lives were threatened by the weightlessness or increased radiation or other effects they might experience up there,” astronomer Jake Foster, from the Royal Observatory Greenwich, told The Guardian in 2023.

But “modern missions are less concerned about testing the dangers of space and focus more on researching the long-term effects of living in space,” he explained. “That, in turn, reflects an interest in developing long-term missions such as trips to Mars.”

As for Félicette – well, her story was mostly forgotten. But visit the International Space University at Strasbourg, and you might see a small monument to her sacrifice: a bronze statue, depicting her perched on top of the Earth, looking up toward the sky. It may have taken the best part of six decades and an online Kickstarter campaign to get there, but Félicette finally got the recognition she deserved.

“It’s crazy to think a video I put online almost two and a half years ago has resulted in this,” Matthew Serge Guy, who created the campaign, wrote in 2020. “The internet’s an alright place sometimes.”

Source Link: Remembering Félicette, The Only Cat To Ever Go To Space