Even when humans don’t drive animals to extinction, our footprint on this planet is so deep we often change the species around us. The latest example is the rhinoceros. Several species and subspecies teeter on the brink of annihilation. Others are doing better, but they’re less well-endowed in the horn department than their ancestors, possibly storing up trouble for the future.

Oscar Wilson, then at the University of Cambridge measured the lengths of horns in 80 photographs of rhinoceroses taken between 1862 and 2018 and housed on the Rhino Resource Center website. The five different species varied in their horn length from the beginning, but Wilson and co-authors report in the journal People and Nature that the horns of all five have shrunk over this period, although the Javan sample of just five is probably too small to rely on. The shrinkage occurred both in absolute terms, and relative to the size of the rhino.

Although hard to prove, the explanation is almost certainly that poachers will go to much greater lengths to kill a rhino with a large horn. Smaller-horned beasts have therefore become more likely to survive and pass on the trait to their offspring.

The observations had to be made using photographs because few horns are available for study – if they haven’t been stolen for sale they’re too closely guarded to access. “We were really excited that we could find evidence from photographs that rhino horns have become shorter over time,” Wilson said in a statement. “They’re probably one of the hardest things to work on in natural history because of the security concerns.”

Wilson’s findings match those from other species. Half the female elephants in Mozambique have given up on tusks altogether, to escape poaching. That process seems to have occurred primarily in the 15 years the nation suffered a civil war, which allowed poachers to operate virtually unchecked, so 156 years of rhino hunting could certainly have an effect.

Nevertheless, horns are not just rhinos’ hood ornaments. They use them to fight off more traditional threats such as lions, as well as in conflicts over mating. Some even use their horns to bring food to their mouths. Hunting pressure operated against forces favoring the survival of well-horned rhinos. For some rhinos, the loss of horn length could prove a problem at species level, whereas those populations engaged in zero-sum battles for social dominance may collectively lose nothing.

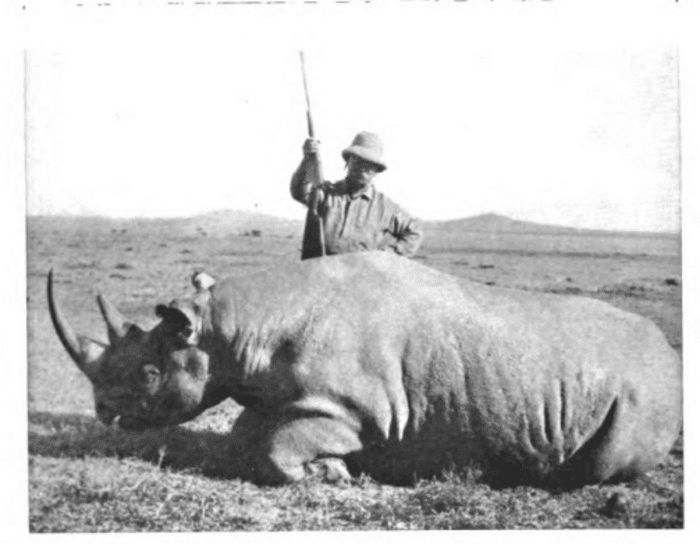

Ironically, Wilson was only able to conduct this study because hunters once proudly posed with the animal they had slain. Today, hunting is more likely to be done in secrecy by poachers whose sole goal is a share of the wealth the horn brings in certain Asian markets.

After leaving the White House, Theodore Roosevelt spent a lot of time hunting, his equivalent of golf. He’s pictured here standing over a black rhino he shot in 1911. Image credit: Public domain via Rhino Resource Center

The study also included analysis of drawings and photographs of rhinoceroses dating back as far as Albrecht Dürer’s famous 1515 woodcut to see how people have perceived rhinos over that time.

These show a sharp movement around 1950 from seeing rhinos as something to kill, to a creature to be valued alive. Pre the transition, those images that didn’t portray vanquished rhinos presented them as terrifying, which probably helped legitimize the killing. The shift to more positive art may have contributed to the fact that four of the five species are recovering, albeit often from very low bases.

The study is open access and published in People and Nature.

Source Link: Rhino Horns Are Shrinking And Poaching Is Probably To Blame