Saber teeth such as those that belonged to apex Ice Age predators were superbly shaped for puncturing prey and subduing them, a new study has found. In one sense that is unsurprising, since many different mammalian carnivores evolved similar shapes independently. On the other hand, it raises the question of why none of the species that possessed these weapons survived far into the Holocene, but the authors have some insight into that question as well.

Smilodon, also known as the saber-toothed cat or less accurately the saber-toothed tiger, has earned a place among the past’s most terrifying hunters, along with T-Rex and Megalodon. If Pleistocene Park ever becomes a movie franchise, not a crowd-funded research project, Smilodons will probably have star billing for the visceral fear those long upper canines instill in us all. However, they were just the more recent of at least five mammal and mammal precursor families that evolved similar teeth – the first in the Permian before dinosaurs appeared – despite not being closely related to each other.

Dr Tahlia Pollock of the University of Bristol and colleagues were intrigued by this convergent evolution, combined with their owners’ extinction. It’s clear that anything that long and sharp could be very handy for subduing prey. On the other hand, the longer and thinner a tooth becomes, the greater the danger of it breaking.

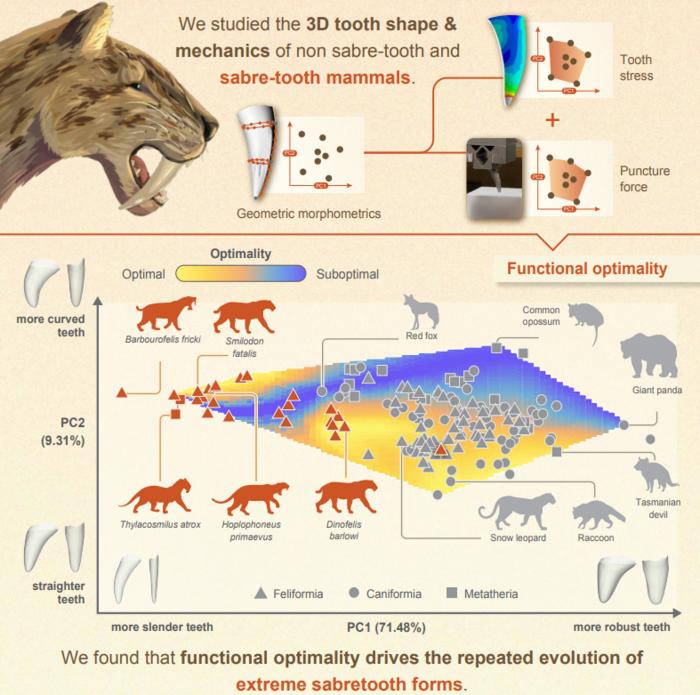

To test if struggling bison or bouncing kangaroos put too much strain on Smilodon or Thylacosmilus’s teeth, Pollock and colleagues made 3D-printed steel replicas of teeth from 25 saber-toothed species and conducted biting experiments on gelatin blocks. They also ran computer simulations to see where strains would be highest. Results were compared with teeth belonging to 70 other species of carnivorous mammals.

“Our study helps us better understand how extreme adaptations evolve – not just in sabre-toothed predators but across nature,” Pollock said in a statement. “By combining biomechanics and evolutionary theory, we can uncover how natural selection shapes animals to perform specific tasks.”

The work indicated that the teeth superbly balanced the sharpness required for puncturing prey’s often tough hides while being thick enough to resist breaking, however hard victims struggled. The exact shape of each species’ teeth varied. Previous work had divided saber-toothed predators into straight “dirk-toothed” and curved “scimitar-toothed” categories, but Pollock and colleagues found that like most binaries, this was an illusion. Instead, ancient saber-toothed animals had a spectrum of curvatures. Sometimes several different saber shapes overlap in time and place, perhaps suggesting differing preferred prey among their owners.

Although a range of saber-tooth shapes work well, there is a suboptimal valley that may have caught some species.

Image Credit: Tahlia Pollock

As well as targeting different species, the variation in shape may have reflected different killing styles, with slender teeth suited to ripping into the softer but harder-to-reach parts of prey. Meanwhile, species that preferred a “clamp-and-hold” approach familiar from documentaries of modern-day big cats evolved more robust teeth.

While these findings answer the question of why this shape keeps emerging, they increase the need to explain what went wrong for their owners.

The authors think the most likely explanation is that the teeth made predators highly specialized in their prey. Not only were saber teeth, in general, unsuited to catching smaller prey, but the thinner and more curved shapes may have only worked against one or two available species.

Specialization would have been an advantage under consistent conditions. When the climate changed, or new arrivals such as humans made certain animals rare, saber-toothed species were less able to make do with alternatives than hunters with less fearsome mouthparts. Even if newly available prey were well-suited to saber-toothed attack, sometimes the best design was one that had been outcompeted long before.

The study is published in Current Biology

Source Link: Saber-Teeth Are Perfect For Biting So Why Are Their Owners All Extinct?