A series of footprints once attributed to a “swimming brontosaur” has a far more likely explanation, new research has found. Although the work focuses on a single famous case, it has implications worldwide for tracks that bafflingly only show front, or rear, prints from large four-legged sauropods. Despite this, the lead author of the research thinks these mighty beasts probably could swim, but didn’t leave us handy signs.

ADVERTISEMENT

Dinosaur footprints are far more common than their bones. Often when we find them all we have is a single print, but there are also plenty of trackways around the world, providing useful information such as the length of the maker’s stride. When the dinosaurs responsible are theropods, these are naturally of the hind feet only, but for sauropods, we’d expect to get both front and back prints, and usually we do.

There are, however, a few places around the world where a series of prints, apparently from a single animal, can be seen, and these include either front or back feet, but not both. Possibly the most famous of these is in South Texas on land that is now part of the Mayan Dude Ranch. When Roland Bird, one of the most prolific finders of dinosaur relics of the mid-20th century, uncovered the tracks he proclaimed that the dinosaurs were walking on their hands.

Improbable as the idea of beasts many times heavier than elephants engaging in such shenanigans might seem, Bird had an explanation. The dinosaurs were partially wading through chest-high water, their legs floating out behind them as they hauled themselves forward with their giant front feet, Bird proposed. One partial hind print was also found, but Bird explained it as the maker “kicking out” to change course.

The idea has been taken up to explain similar tracks elsewhere. Some of these have sauropod rear prints instead, suggesting a different swim/wade style, perhaps with a sort of breaststroke replacing the kicking motion one can imagine at the Dude Ranch.

Dr Thomas Adams of the Witte Museum, San Antonio, and colleagues gained access to the tracks from the current owners of the site and have studied the tracks in more detail than Bird did. They’ve also used the tracks as an opportunity to train their students, gaining extra eyes in the process.

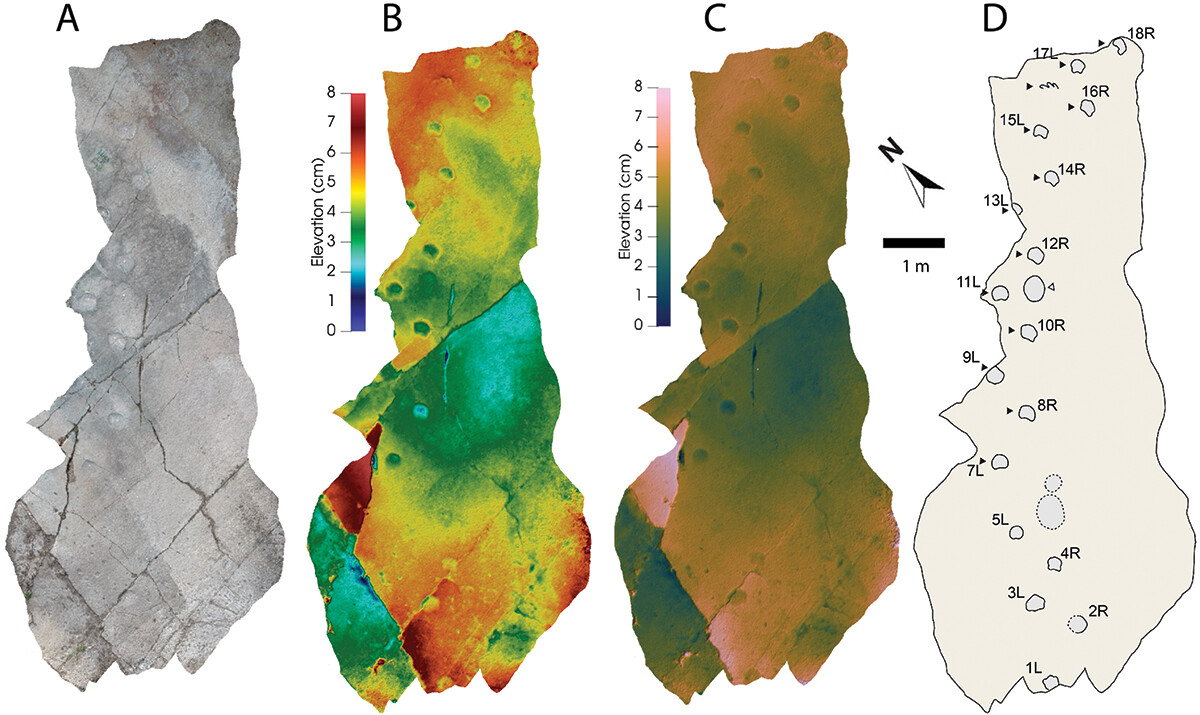

This trackway, discovered in 1940 sparked the belief giant sauropods waded on their front feet. It’s shown here in ordinary light, two color schemes where color indicates depth and outline.

Image Credit: Adams et al., 2025, Historical Biology

“This project has a lot of people involved with it,” Adams told IFLScience. “We get to work with people from several universities, including experts in many different fields, and they are bringing their students, giving them experience.” Because the site is relatively handy to San Antonio, it’s an opportunity most wouldn’t normally get until later in their careers.

Besides the trackway Bird found, the team discovered two other trackways, which, Adams says, are “all on the same layer, despite the distance between them.” Consequently, the researchers are confident it was deposited at the same time, with calcium carbonate crystalizing in what Adams told IFLScience is “a very fast process.” That makes it unlikely that some of the tracks could have been made when the area was deep underwater, with others made in shallow water or none at all.

In that context, it’s very relevant one track is from a theropod too small to have been able to walk if the water was chest-deep to a giant sauropod.

Meanwhile, hind prints have been revealed in the second sauropod track, although not as deep or clear as the forefeet prints. This proves the second sauropod was walking normally. If there were only a few days between the making of the two tracks, Adams doesn’t consider it plausible the water height could have changed that much in between. The process by which the sediments turned to stone is also indicative of being under at most a meter (3 feet) of water.

The second sauropod track, which has marks from both the front and hind feet.

Image Credit: Adams et al., 2025, Historical Biology

Why then are there no hindprints on the original trackway? Adams and co-authors argue the maker, whose exact species is unknown, carried their mass forwards, so these legs had more weight on them, and the footprints went deeper.

“If you are walking along over soft sediment, as your foot displaces the sediment it goes in multiple directions, including down,” Adams said. If, after it hardens, the top layer is less resilient than those below, the upper layers can be eroded away. All that is left is where the print pushed through to lower sedimentary layers, known as an “undertrack”. With somewhat less weight on the rear, the hind prints might not make it through to the lower levels, and when the top layers are lost, those prints go with them.

These theropod prints were made in the same layer as the two sets of sauropods, and are also inconsistent with it being deep underwater at the time.

Image Credit: Adams et al., 2025, Historical Biology

This is easy to understand but raises the question of trackways composed of sauropod rear tracks elsewhere. Sometimes, Adams told IFLScience, this is because the hind foot lands on top of the front print, erasing it. More often it’s a matter of evolution. “Jurassic sauropods’ forelimbs were shorter,” Adams said, and most of their mass was further back, making rear-only prints possible. By the early Cretaceous, when these tracks were made, the big sauropods had more mass on their front limbs, so it was these feet that went deeper. This could be a rare case of Jurassic Park being scientifically accurate.

Sad as it may be to lose hope that the largest beasts to ever walk the Earth sometimes got around on two legs, Adams thinks they probably did swim.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Most animals can swim,” he told IFLScience. “I can’t think of any good examples of animals that can’t swim if they have to.” Elephants are the closest modern equivalents for size, and, as Adams points out, “they can move from island to island,” acknowledging they have a “built-in snorkel.”

Bird’s work may no longer stand (at least not on two legs), but Adams says the site remains “a cultural resource for Texas” as well as a training site for students. The trackway is a reminder of both ancient history, and significant steps forward for its interpretation in more recent times.

The study is open access in Historical Biology.

Source Link: Sadly, Famous Dinosaur Tracks Were Not Made By Sauropods Walking On Their Hands