Certain genes in the human brain are active in 12-hour cycles, a new study has demonstrated for the first time. By studying the brains of patients with schizophrenia, the researchers discovered that many of these rhythms are altered or missing in these individuals, which could help explain some of the clinical features of the condition.

We’re more used to thinking of the human body operating on a 24-hour cycle, what’s known as the circadian rhythm. It’s not just humans who keep to this schedule – it’s common throughout the animal kingdom, and even bacteria have been found to make use of predictable daily changes.

However, it’s long been suspected that certain aspects of human physiology may instead operate on a 12-hour cycle. These shorter rhythms have already been observed in nature, notably in marine mammals that are affected by the movement of the tides. Now, for the first time, a study led by Madeline R. Scott of the University of Pittsburgh has found evidence of these 12-hour rhythms in the human brain, making some crucial links between this rhythmic activity and schizophrenia.

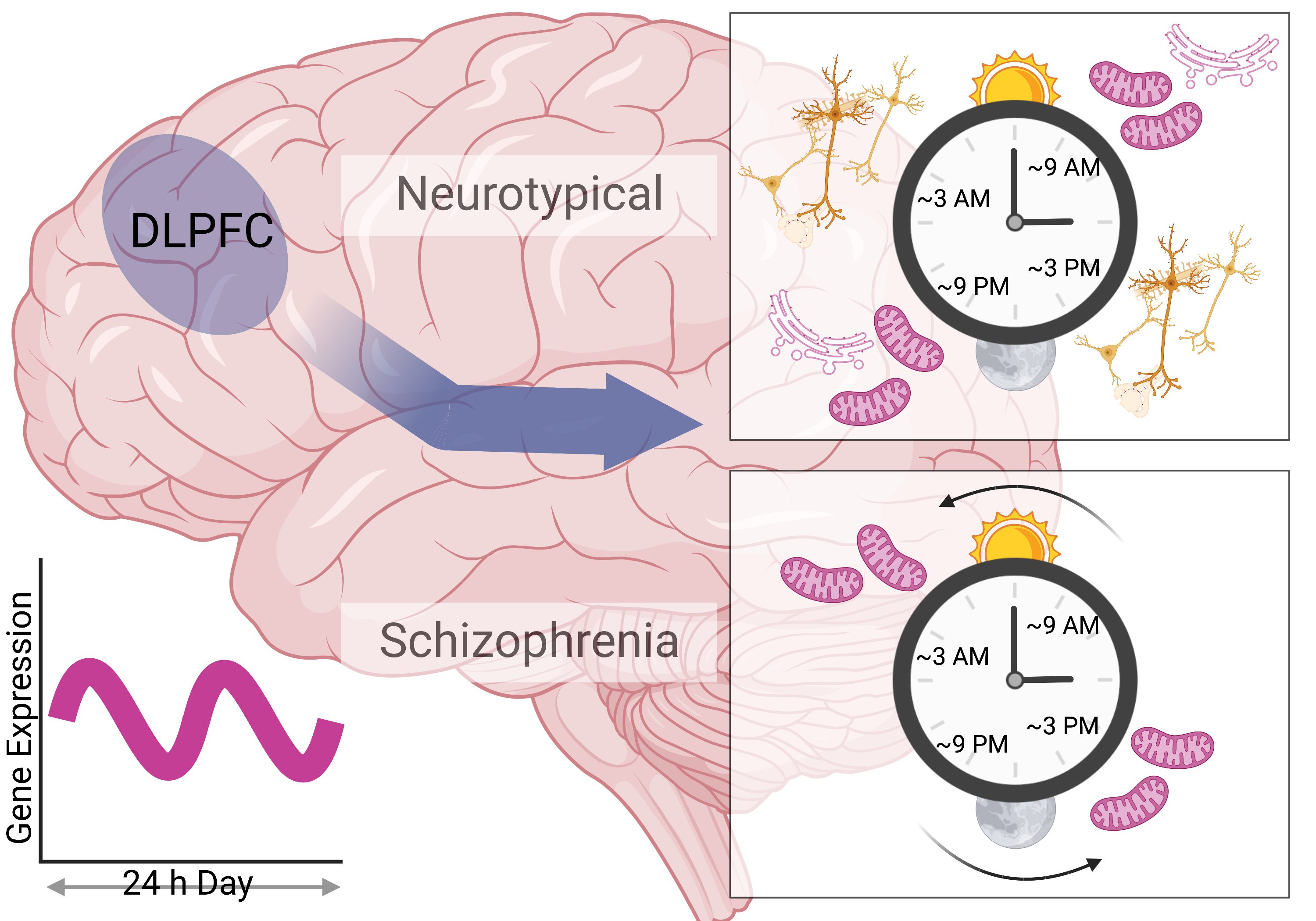

Disruption of the circadian rhythm is often among the first signs of schizophrenia. Patients often report sleep disturbances, such as being unable to fall asleep or only sleeping for short periods. Previous studies have also shown abnormal gene expression in a region of the brain called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), which is associated with some of the cognitive symptoms that people with schizophrenia experience.

Since it’s not possible to measure gene activity in the brains of living people, the researchers used post-mortem brains donated by people with and without schizophrenia.

Focusing on the DLPFC, they identified several genes that usually work on a 12-hour cycle. Genes associated with building connections between nerve cells were more active in the afternoon and during the night. Genes associated with the energy supply to cells peaked in the morning and evening.

When these findings were compared with those from the brains of patients with schizophrenia, the difference was stark. The rhythmic activity in the genes associated with building bridges between nerve cells was lost entirely. In the genes related to energy, the 12-hour cycle was still present, but the peaks in activity had shifted to abnormal times.

“We find that the human brain has not only circadian (24 hour) rhythms in gene expression but also 12-hour rhythms in a number of genes that are important for cellular function and neuronal maintenance,” summarized study author Colleen A. McClung, in a statement. “Many of these gene expression rhythms are lost in people with schizophrenia, and there is a dramatic shift in the timing of rhythms in [cellular energy]-related transcripts.”

McClung added that this could mean that brain cells are not functioning at their best “at the times of day when cellular energy is needed the most.”

It’s unclear whether these abnormal rhythms are themselves the cause of some of the symptoms of schizophrenia, or whether they could have arisen from, for example, medication use or disturbed sleep. More studies will be needed to investigate this, but these findings have provided the vital first steps.

The study is published in PLOS Biology.

Source Link: Schizophrenia Linked To Disrupted Or Missing 12-Hour Gene Cycles In The Brain