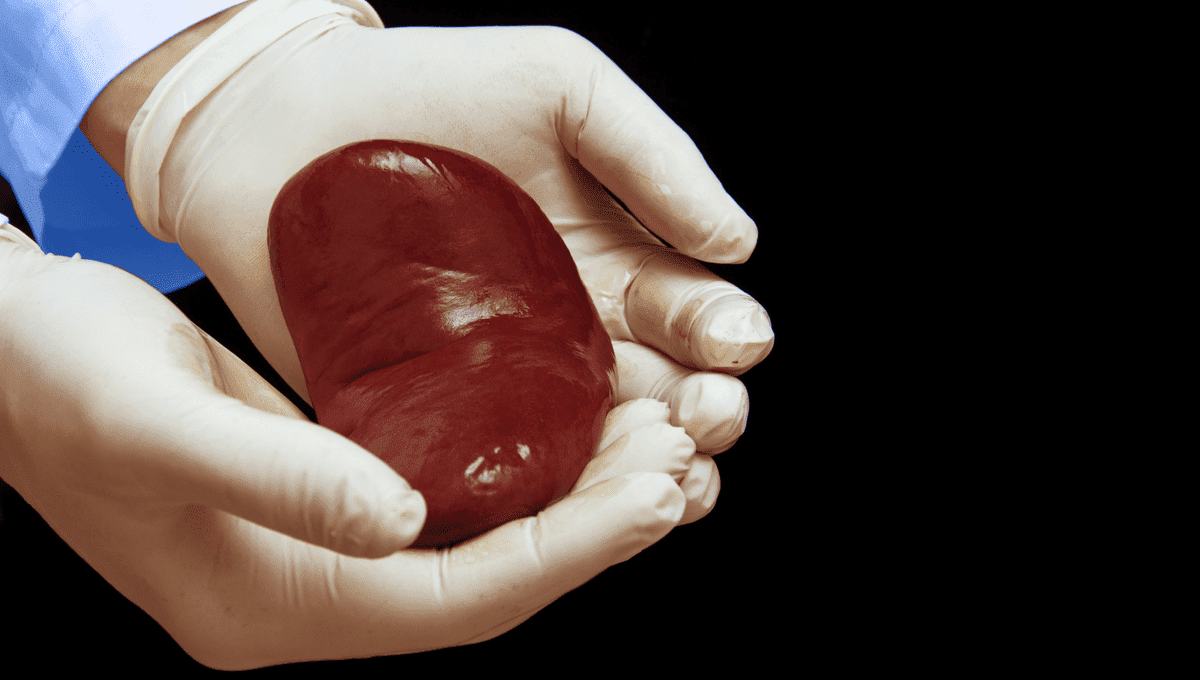

In a breakthrough described as “game-changing” for patients in need of kidney transplants, researchers have discovered a way to change the blood type of a donor kidney – thus making it suitable for transplant into just about anybody who needs it. Not only is this an impressive feat in its own right, but it also has the potential to tackle long-standing inequalities, providing vital healthcare to thousands of people disadvantaged by the current system.

Have you ever wondered why organ and blood donation services are always after more ethnic minority donors? It’s to improve the chances of success for ethnic minority recipients – while it’s far from impossible for an organ donor and recipient to have different ethnicities, people with rarer immune markers are just more likely to match better with someone from their own background.

The majority of transplanted organs, though, come from white donors – meaning that patients from other ethnic groups are often left waiting for their life-saving treatments, sometimes for double or triple the times experienced by their white peers.

“One of the biggest restrictions to who a donated kidney can be transplanted to is the fact that you have to be blood group compatible,” explained Mike Nicholson, the professor of transplant surgery who led the project, in a statement.

“The reason for this is that you have antigens and markers on your cells that can be either A or B. Your body naturally produces antibodies against the ones you don’t have.”

It’s the same reason you can’t just swap blood with Jeff from down the street – and, more seriously, why some people require anti-D injections during pregnancy to stop their body from aborting the fetus: if cells with the wrong blood markers enter our systems, they will be attacked by our bodies’ natural defense mechanisms, and the “intruder” will be rejected.

There’s one exception: type O negative blood, also known as the “universal donor.” This type has neither A nor B markers, and no RhD antigen either. It’s perfect for transplants and transfusions because there’s nothing in it that can provoke an antibody response.

Unfortunately, type O negative is also fairly rare: only about one in every 15 Americans fall into this category. That’s 11 times as many as those with type AB negative blood – the rarest of all – but for comparison, more than one in three people in the US are thought to be O positive.

That’s only the broad picture. “Blood group classification is also determined via ethnicity,” pointed out Nicholson, “and ethnic minority groups are more likely to have the rarer B type.”

In lieu of recruiting more donors from ethnic minority backgrounds – which can be difficult due to cultural or religious taboos – the dream would be to find a way to “convert” organs from one blood type to another. And that’s exactly what the researchers did.

Using a normothermic perfusion machine – a device that passes oxygenated blood through human kidneys to help preserve them for future use – the team flushed blood infused with a particular enzyme through a deceased kidney.

This enzyme acted like “molecular scissors,” the researchers explained, snipping away the markers within the blood vessels of the kidney that defined the organ’s blood type. The result: no more antigens – or in other words, a brand-new type O kidney.

“Our confidence was really boosted after we applied the enzyme to a piece of human kidney tissue and saw very quickly that the antigens were removed,” said PhD student Serena MacMillan, who worked on the project with Nicholson.

“After this, we knew that the process is feasible, and we just had to scale up the project to apply the enzyme to full-size human kidneys,” MacMillan explained. “We saw in a matter of just a few hours that we had converted a B type kidney into an O type.”

With the project a success, the next step is to see whether the technique can be used in a clinical setting. If it can, it would be “potentially game-changing,” according to Dr Aisling McMahon, executive director of research at Kidney Research UK.

“It is incredibly impressive to see the progress that the team has made in such a short space of time, and we are excited to see the next steps,” she said. “We know that people from minority ethnic groups can wait much longer for a transplant as they are less likely to be a blood-type match with the organs available. This research offers a glimmer of hope to over 1,000 people from minority ethnic groups who are waiting for a kidney.”

Source Link: Scientists Change Blood Type Of Kidney, Offering New Hope For Thousands Of Transplants