Researchers have found a new phenomenon in 2D conductive systems that offers increased terahertz detector performance.

When 2D electron systems are exposed to terahertz waves, a group of Cavendish Laboratory researchers and collaborators from the Universities of Augsburg and Lancaster have discovered a novel physical phenomenon.

To begin, what are terahertz vibrations exactly? “We communicate using microwave-transmitting cell phones and night vision infrared cameras.” Terahertz is a form of electromagnetic radiation that falls somewhere between microwave and infrared “But there are currently no sources or detectors of this type of radiation that are cheap, efficient, and easy to use,” says Prof. David Ritchie, Head of the Semiconductor Physics Group at the University of Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory. This makes widespread adoption of terahertz technologies challenging.”

In 2002, scientists from the Semiconductor Physics team, in collaboration with researchers from Torino and Pisa in Italy, were the first to show the functioning of quantum cascade lasers at terahertz frequencies. And since, the group has continued to examine and construct functioning terahertz devices that incorporate metamaterials as modulators, and also novel forms of detectors.

Terahertz radiation could have various applications in security, communications, materials science, and medicine if the lack of viable devices could be remedied. Terahertz radiation, for example, can be used to image malignant tissue that isn’t visible to the naked eye. They could be utilized in future generations of safe and quick airport scanners that can identify medications from illegal narcotics and explosives, as well as enable much faster wireless connections than now available.

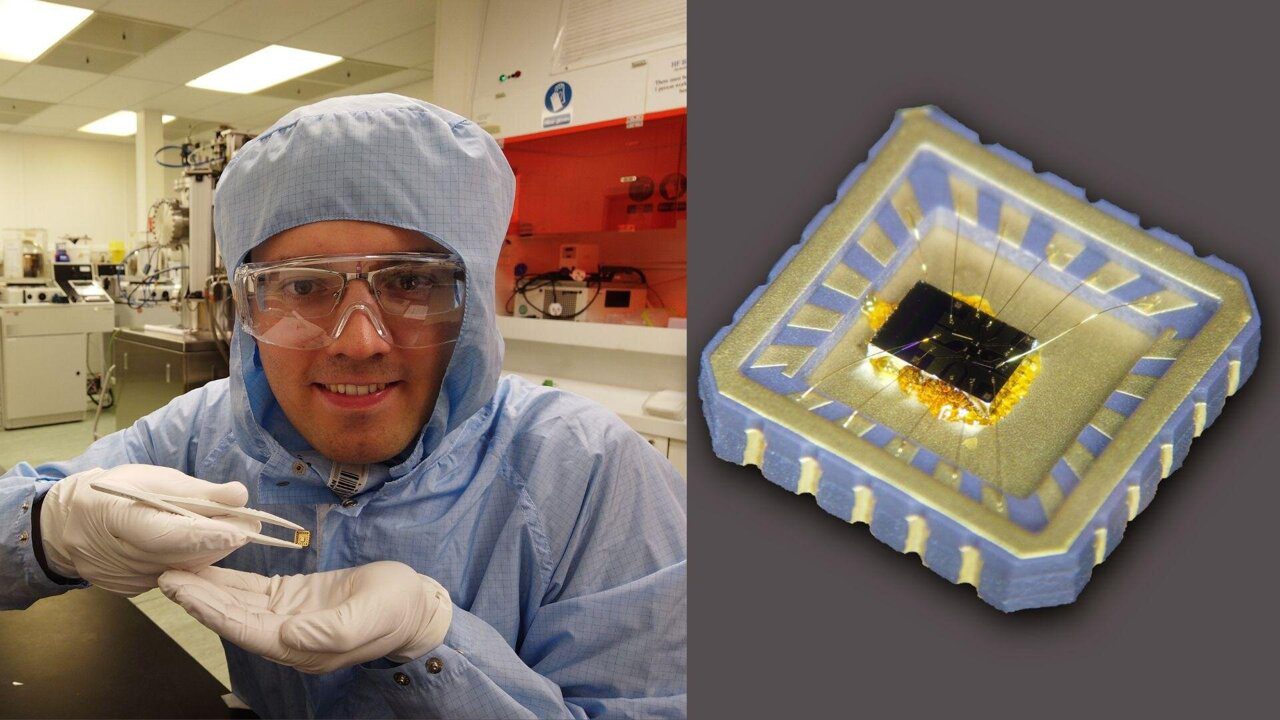

So, what exactly is this new discovery? “We were working on a novel type of terahertz detector,” explains Dr. Wladislaw Michailow, a Jr. Research Associate at Trinity College Cambridge, “but when we measured its efficiency, it turned out that it displayed a significantly greater signal than should be expected theoretically.” As a result, we devised a new explanation.”

Experts believe the reason lies in the way light interacts with materials. At higher frequencies, matter captures light in the form of single photons. This concept, which became the cornerstone of quantum mechanics, also characterized the photoelectric effect, as proposed by Einstein. Quantum photoexcitation is how smartphones’ cameras detect light, as well as how solar cells generate electricity from light.

The well-known photoelectric effect involves incoming photons causing electrons to be released from a conductive material, such as a metal or a semiconductor. In the 3D scenario, photons in the ultraviolet or X-ray spectrum can eject electrons into the vacuum, or they can be discharged into a dielectric in the mid-infrared to a visual spectrum. The finding of a quantum photoexcitation mechanism in the terahertz band that is analogous to the photoelectric effect is the novelty. “We were able to confirm this experimentally,” says Wladislaw, the study’s first author. “The idea that certain effects can exist within highly conductive,2D electron vapors at significantly lower frequencies has not been understood so far.” A teammate from the University of Augsburg in Germany devised the quantitative explanation of the effect, and the multinational team of academics published their study in the journal Science Advances.

The phenomenon was given the name “in-plane photoelectric effect” by the researchers. The researchers highlight various advantages of using this effect for terahertz detection in the associated study. The size of the photoresponse produced by incoming terahertz radiation through the “in-plane photoelectric effect” is substantially higher than expected from other mechanisms formerly to produce a terahertz photoresponse. As a result, the researchers believe that this effect will allow for the creation of terahertz detectors with far higher sensitivity.

Prof Ritchie continues, “This gets us one step closer to getting terahertz technology practical in the reality.”